In qualifying he told her to follow him for a few laps, during which he would deliberately drive at abated speed so that she could keep up with him and learn the racing lines. It worked: she qualified eighth and finished fifth. But I digress. After five rounds of the F1 world championship, having finished second in both Argentina and Monaco, he lay third in the drivers’ standings, behind only Moss (Vanwall; first) and his Ferrari team-mate Hawthorn (second); Collins had scored points only once, at Monaco, finishing third, 18 seconds behind second-placed Musso.

But, now, the ‘troubled soul’ side of the proud Roman’s character entered the equation again. Despite his having inherited a large sum of money on the death of his father, Giuseppe Musso, who was not only a lawyer and a diplomat but also the founder of a successful film production company, 33-year-old Luigi had fallen heavily into debt, having lost a fortune as a result of a decreasingly controllable gambling addiction and an ill-judged decision to invest in a hare-brained scheme to import American cars to Italy.

It is said that he owed money to the Mafia. The next F1 grand prix was the French, at Reims, heavily sponsored by BP, for which was offered the richest purse of the year, 10 million francs, the equivalent of £9500, which is about £275,000 in today’s money. The winner’s share was five million francs, or around £4250, which equates to £137,500 today. Undoubtedly, the pressure to win the race for Musso was financial as well as sporting.

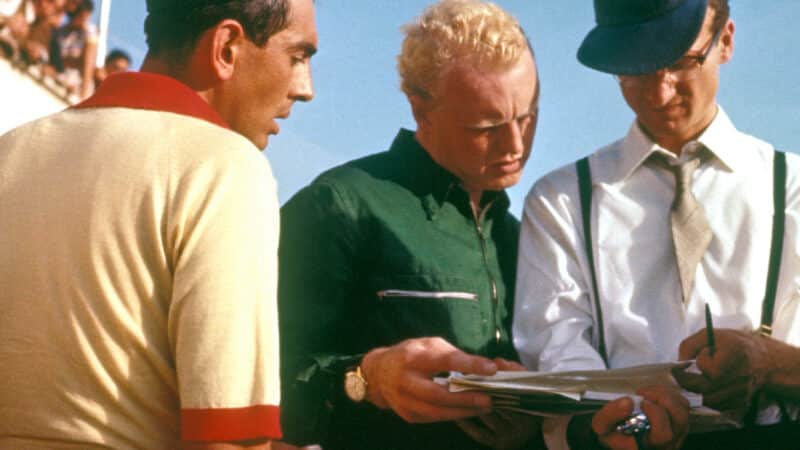

Luigi Musso (left) speaks with Mike Hawthorn (middle) and Ferrari F1 team manager Romolo Tavoni (right)

Grand Prix Photo

Hawthorn took the pole; Musso qualified second; Collins started fourth. The next day Hawthorn led, Musso in second place. Pushing as hard as he dared — too hard therefore — on lap 10 he ran wide at Turn 1, the not-quite-flat 155mph (249km/h) Courbe du Calvaire, and he dropped a wheel into a ditch a metre or so beyond the asphalt. It would be fair to say that in the late 1950s Reims was not a circuit on which track limits could be abused. Musso’s car flipped and rolled, and that was that. Hawthorn won the race — and the money that Musso had died trying to chase.

Perhaps — as Breschi, Musso’s girlfriend, would later claim — Hawthorn and Collins had indeed been “united against Luigi”, or perhaps they were simply good friends who sought to help each other from time to time. We will never know. What we do know is what Hawthorn wrote in the book he wrote about 1958, Champion Year, the title unimaginatively but accurately reflecting his going on to win the F1 drivers’ world championship at the end of the season: “I had never known him [Musso] very well, although he was a most likeable person, but he was too conscious of the fact that he was the only Italian driver of note [after the death of Castellotti in 1957]. It made him try too hard. He felt that he must press on for the sake of national honour. Just how the accident happened is a mystery, but it would seem that he went into the corner a shade too quickly, got into trouble, and could not get out of it.”

After the race Ferrari said: “I have won at Reims, but the price is too high, for I have lost the only Italian driver who mattered in grand prix racing.”

Hawthorn attributed Musso’s death to fighting for “national honour”

Getty Images

Two weeks later, at Silverstone, Collins won from Hawthorn, the ‘mon ami mates’ delivering a Ferrari 1-2. A fortnight after that, at Nürburgring, Collins strayed off the racing line on the fast and bumpy Pflanzgarten section; he dropped a wheel into a ditch, just as Musso had done at Reims only a month before, and his Ferrari was launched into the air and landed upside-down. He succumbed to his injuries at a hospital in Bonn early that evening.

Five months after that, driving his Mk1 Jag too fast on a notoriously dangerous section of the Guildford bypass made slippery by recent rain, Hawthorn lost control, crashed, and was also killed. Yes, it was F1, but not as we now know it, thank god.