On race day Andretti jumped the start, although he was not aware of that at the time and he disputed it afterwards: “Man, I tell ya, I didn’t jump that start. This is Formula 1. You don’t fool around.” It was academic in the end because, although he had been leading comfortably, posting the race’s fastest lap on the way, his engine gave up after 45 of the 72 laps. Amon had been running comfortably in fourth place, behind Andretti, Scheckter, and Scheckter’s Tyrrell team-mate Depailler, whom he had been catching when sudden steering failure under braking for Startkurvan, a fast 170-degree right-hander, caused his Ensign to careen straight on through two rows of catch fencing into the guardrail behind. To the surprise of the nearby photographers and marshals, he was unhurt. “I sat still in the car for a few seconds, sort of taking in the fact that I wasn’t dead,” he said that evening. “It was a massive impact, the most frightening experience I’ve ever had.”

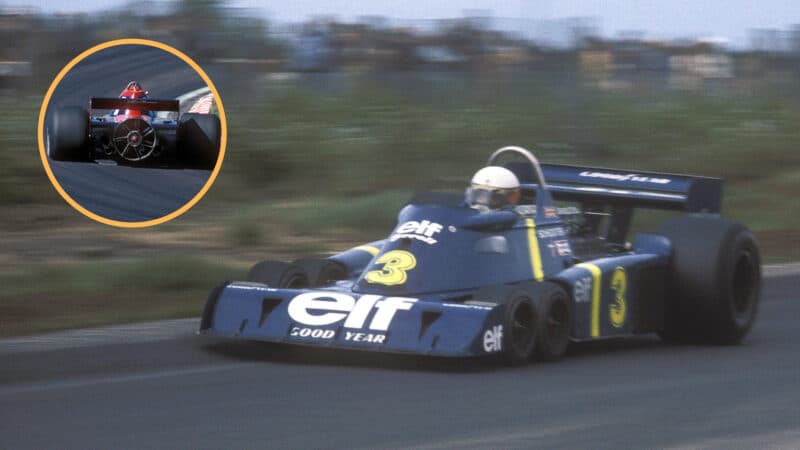

So Scheckter and Depailler finished one-two for Tyrrell, as they had two years before, but this time it was a 12-wheeled Tyrrell one-two rather than an eight-wheeled one. The Tyrrell P34 would never win an F1 grand prix again, and now no six-wheeler ever will, because the FIA long ago mandated that all F1 cars must have four wheels. Jody hated the car. “We’d have been better off if we’d junked the six-wheeler and carried on with the 007 [the four-wheeled Tyrrell in which he had won F1 grands prix in both 1974 and 1975],” he once told me. “But Patrick quite liked the six-wheeler. He was always enthusiastic like that, whereas I looked at things more dispassionately. I didn’t like the way it behaved under braking. When you braked hard, you’d have six wheels that could lock up, not four. So you had a 50 per cent greater chance of a lock-up. And when you lock up a wheel like that, you have to ever so slightly ease up on the brake pedal to get the locked wheel turning again, and that compromises your braking. It happened a lot with the six-wheeler, obviously. I was very happy to be back on four wheels the following year, in a Wolf.”

Scheckter scores first and last victory for a six-wheeled F1 car in 1976 at Anderstorp

Grand Prix Photo

More than 20 years later, in January 1997, I interviewed Ken Tyrrell in his eponymous F1 team’s famously ramshackle headquarters in Ockham, Surrey. We talked mostly about the season ahead, for Tyrrell was still an F1 entrant at that time, but I could not resist chucking him a question about the P34. “Did that car give you a lot of pleasure?” I ventured.

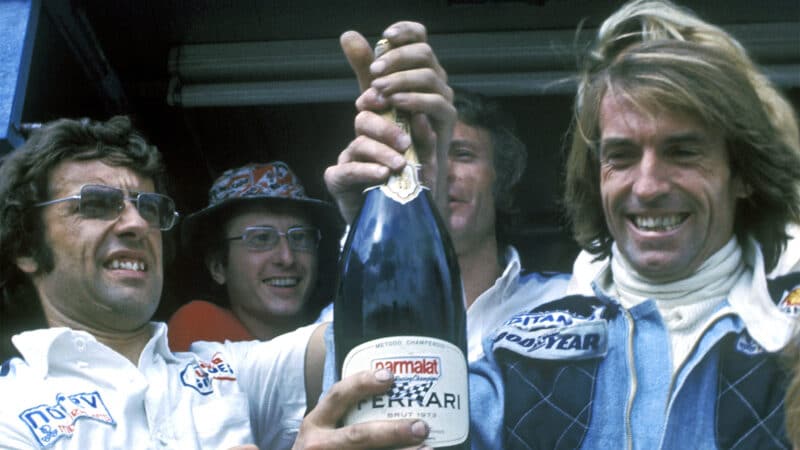

“Oh yes,” he replied, with his trademark hearty guffaw, “and you’ll like this story. After Sweden 1976, when we finished one-two with the six-wheelers, Luca di Montezemolo, who was the very young team manager at Ferrari, came up to me after the race, went down on his knees, and clasped his hands together. ‘Ken, that was absolutely fantastic,’ he said. Two years ago, at Imola, I was talking to him in the pits, I reminded him of it, and he said he didn’t remember it. But I reckon he did. It was just a bit difficult for the now president of Ferrari to reminisce about going down on his knees to praise Ken Tyrrell, I think!”