Williams used uncompetitive Judd engines in 1988, and got lost as it tried to develop an active ride system that Mansell hated: “In the aftermath of losing Honda we tried too hard really, and gave ourselves too many engineering challenges,” says Head. “We had the débâcle of active ride in 1988, when we had to take it off the car for all sorts of reasons.”

Head insists that he never felt frustrated as McLaren scored success after success with Honda: “I was up to my eyeballs in work, and I’ve never been one to look backwards and say something’s not fair. I think if I ever had any of that in me as my character, my father would have kicked it out of me when I was 16 or something, because he was a fairly tough character!

“And so I didn’t sit and look back, it was just get on with the future. And we signed up with Renault, and I think we won a couple of races with Renault in the first year. The belt drive was pretty unreliable. So it wasn’t really a championship potential engine in 1989. It took us ’89 and ’90, and then we started getting serious in ’91.

“And I accept full blame for not winning the championship in 1991. It was our first semi-automatic gearbox, and for the most stupid of reasons it was unreliable. But after three or four races, we considerably outscored McLaren, but we weren’t able to catch up with them.”

“And by that time the active car was beginning to do better lap times than the passive car, and delivering the promise that was always seen theoretically.”

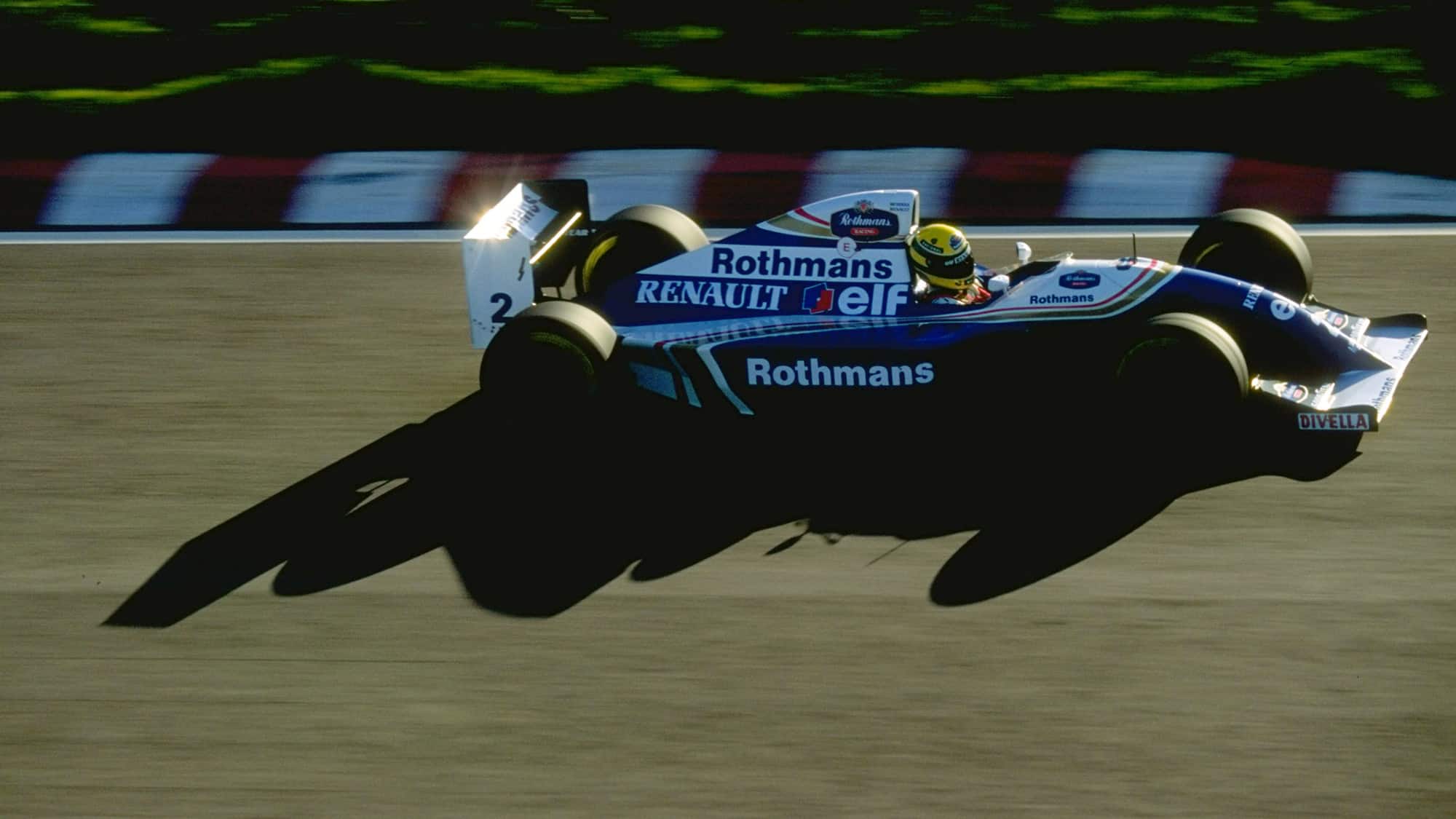

In 1991 Williams had perfected the active suspension system on the FW14, and the FW14B of 1992 was to be dominant, helped by the input of the brilliant Adrian Newey, who became a huge influence on the team.

Unstoppable: Mansell and the FW14B

Grand Prix Photo

“In 1991 Nigel and Riccardo Patrese were very close together on performance, but in ’92 Nigel stepped up relative to Riccardo,” says Head. “The main reason was the feeling and feedback from the active system. Nigel worked out that providing you could persuade yourself to trust it, it would be there once you had got into the corner. Nigel adapted to it, but Riccardo always wished it was a standard car.

“The good work was done over the winter, and then it was a question of just running the car. I think by the end of the year McLaren were beginning to make good progress with their active system, and they were getting it to work pretty well.”