Two weeks previously, at Anderstorp, Sweden, the F1 world had been pitched into political turmoil when Lauda had won easily in the Brabham BT46B ‘fan car’. That rather crude but incredibly effective machine was not banned, as has often been reported, but was instead withdrawn by Brabham boss Bernie Ecclestone, seeing the bigger picture as he did more often than he is usually given credit for doing, quickly realising that the car was so much faster than anything else that it would (1) win everywhere and (2) force all the other teams to embark on the costly process of creating fan cars of their own. So the Brabham boys suddenly had just two weeks to transport their fan cars from the south of Sweden to the south of England, convert them back to non-fan cars, then transport them from the south of England to the south of France: a big ask for what was then still a small F1 team.

It was already clear that 1978 was going to be an annus horribilis for McLaren

They did more than that, though. “About the only thing that’s the same is the monocoque,” said Gordon Murray, Brabham’s chief designer, talking to journalists in the Paul Ricard pitlane. “We’ve had to change the front and rear suspension, overhaul the cooling system, bring the radiators back up front, and redo lots of bodywork.” It was a massive job but they did it well – and, helped by the long, long straight, on which the Brabham’s powerful Alfa Romeo flat-12 engine was just the ticket, John Watson took the pole with a brilliant lap of 1min 44.41sec. Just four other drivers recorded sub-105sec laps – Andretti (1min 44.46sec), Lauda (1min 44.71sec), Hunt (1min 44.92sec), and Peterson (1min 44.98sec) – and, of the five aces who got into the 44s, the performance that really caught the eye was Hunt’s.

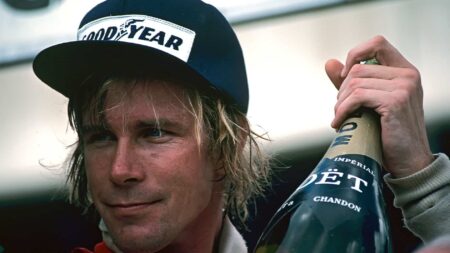

The 1978 French Grand Prix was the ninth race of that F1 season, and it was already clear that 1978 was going to be an annus horribilis for McLaren. The boys from Colnbrook (not yet Woking in those days) had won six F1 grands prix and the F1 drivers’ world championship in 1976, and a further three F1 grands prix in 1977, all nine of those race victories won by Hunt, yet they had not bagged so much as a podium in 1978. The McLaren M26 was two years old – Jochen Mass had given it its F1 grand prix debut at Zandvoort in 1976 – and it was sadly dated by mid-1978. It looked it, too.

Hunt was left to persevere with outdated McLaren M26

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

So, for Hunt to have been able to plant it on the second row at Paul Ricard that year, mixing it with the two super-grippy ground-effect Lotus 79s and the two super-powerful Alfa-engined Brabham BT46s, was remarkable. The M26 had a bog-standard Cosworth V8 and no ground-effect tech at all, remember. Moreover, pace-wise, at least four other Cossie-engined cars had surpassed it over the past half-season, newer and more advanced as they were – the Wolf WR5, the Arrows FA1, the Tyrrell 008, and the Williams FW06 – as had the Ferrari 312 T3 and the Ligier-Matra JS9. But at Paul Ricard none of the drivers of those cars – Jody Scheckter (Wolf), Riccardo Patrese and Rolf Stommelen (Arrows), Patrick Depailler and Didier Pironi (Tyrrell), Alan Jones (Williams), Carlos Reutemann and Gilles Villeneuve (Ferrari), and Jacques Laffite (Ligier-Matra) – had been able to get anywhere near the qualifying time that Hunt had managed to dredge out of his two-year-old McLaren. “Even though the long straight here makes us more competitive than usual against the Lotus 79, I’d still rather have a 79 painted up in Marlboro and Texaco colours and get going in that,” said Hunt, “but unfortunately Colin [Chapman] won’t let us have one.”

On race day Watson made a good start from pole position, and he duly led the field through Turns 1 and 2 into 3, a sharp right-hander that required heavy braking, Andretti tucked in close behind. Hunt had also made a good start, and he had fancied his chances of forcing his McLaren past the Lotus under braking for Turn 3, but that idea was rudely extinguished by Andretti, about whom Hunt was typically scathing after the race: “Mario found himself boxed in behind Wattie so he moved out, which was a pretty stupid thing to do when you’re leading the world championship. All I’d have had to do was lock a wheel and he’d have been in hospital for the rest of the year, and you can’t win races from there. But I decided to be gentlemanly, hit the brakes early to avoid a shunt, and half the field went past me.” Not quite half, to be fair, but he ended up sixth rather than second or third at the end of lap one – and angry.