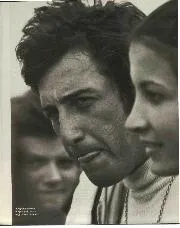

The Sao Paulo native was a hero in his home country, and his day of days came when he won the 1975 Brazilian GP in front of his adoring fans.

Qualifying sixth, the Brabham driver moved into third at the race start behind poleman Jean-Pierre Jarier’s Shadow and early race leader team-mate Carlos Reutemann.

The latter would soon fall back with blistering tyres, and with eight laps to go Jarier’s Shadow failed too, allowing Pace to claim a famous win.

He would tragically die in a plane crash two years later, meaning it would be his only GP victory.

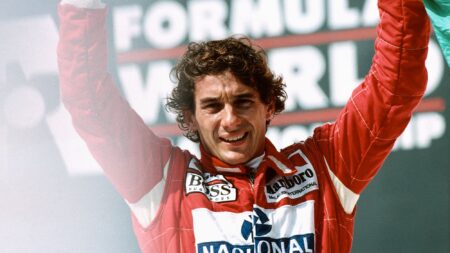

1982: Piquet wins – then doesn’t

Piquet collapses on the podium

Seven years later and another Brazilian came home first after a classic contest – but wasn’t given the race victory.

Held in searing temperatures at Jacarepaguá – in scenes reminiscent of the recent Qatar GP – several drivers suffered from heat stroke, with the ‘winner’ Nelson Piquet fainting on the podium.

At the race start Alain Prost’s Renault bogged down and Gilles Villeneuve leapt into the lead in his Ferrari.