I first made the pilgrimage from London to Silverstone in 1979, in which year, despite the 1975 addition of a chicane in the middle of what had been the white-knuckle-fast Woodcote corner, the Northamptonshire track was still very quick. A circuit had originally been delineated there in 1948, using the perimeter roads of a World War Two airfield, and even in 1979 it still looked that way. It consisted of seven fast corners – Copse, Maggotts and Becketts (two entirely separate turns in those days), Chapel, Stowe, Club and Abbey, and one chicane, the aforementioned Woodcote.

Above I described the 1979-model-year Silverstone as “very quick” — in fact by 1979 it had suddenly become incredibly quick. Why so? Well, in the two years since Silverstone had last hosted a British Grand Prix, the design of F1 cars had undergone a revolution: ground effect. In 1977 the pole had been taken by James Hunt in a McLaren M26, one of the last iterations of the kind of garagiste F1 car that could be uncharitably but not unfairly characterised as a roller-skate onto which had been bolted a Cosworth DFV V8, a Hewland FG400 manual five- or (in McLaren’s case) six-speeder, four fat Goodyears, and rudimentary wings front and rear. Hunt’s 1977 pole time had been 1min 18.49sec.

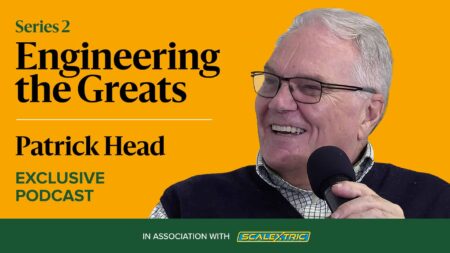

By 1979, in a Williams FW07 roller-skate onto which had been bolted the exact same engine, gearbox and tyres, Alan Jones bagged the pole with a lap of 1min 11.88sec. Where did those seven seconds come from? From sidepod-housed venturi – ground effect – that’s where, which had enabled Mario Andretti’s, Ronnie Peterson’s and (after Peterson had been killed at Monza) Jean-Pierre Jarier’s Lotus 79s to paint the F1 world’s race tracks black and gold in 1978, and whose efficacy had been taken to a whole new level by Patrick Head, Frank Dernie and Neil Oatley in the shape of the 1979 Williams FW07, whose cornering grip was truly leech-like. Jones’s 1979 British Grand Prix pole lap in the car equated to an average speed of a smidgen less than 147mph (nearly 237km/h): pretty tasty for a car powered by an engine designed in the 1960s.

Regazzoni heads to victory in the leech-like Williams

Hoch Zwei/Corbis via Getty Image

The next day I visited Silverstone for the first time, aged 16. I sat in a grandstand opposite the pits, and watched a lacklustre race. Jones cantered off into the distance, leading the first 38 laps with visible ease, until water pump failure stopped him in his tracks. The win was thus taken by his Williams team-mate Clay Regazzoni who, at nearly 40, was no longer as quick as he had been when younger, especially in qualifying (his best quali lap that weekend had been 1.23sec slower than 32-year-old Jones’s); but, such was his Williams’ superiority, he still lapped every car except the Renault RS10 of Rene Arnoux, which he beat by ‘only’ 24.28sec. It is safe to say that, had Jones’s FW07 lasted the distance, he would have lapped everyone except Regazzoni.