“[But] on the MP4/6, the two surfaces that run from the front to the back of the monocoque are on a curve, they don’t actually change direction with an angle – it’s a flowing surface.

“We wanted to reduce the number of changes of angles that the [carbon-]fibres had to go around, to improve torsional stiffness.”

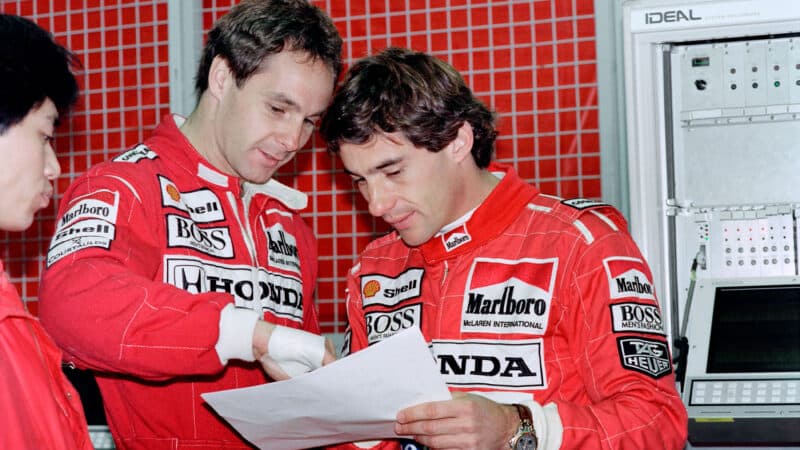

Not that this initially appeased Senna or his team-mate Gerhard Berger much.

“They thought the power wasn’t enough,” recalls Jeffreys. “And Honda said ‘We’re just not running it at full power, we would prefer the reliability.’

“That was it, it wasn’t powerful enough, and it was heavy. So there was concern, even though we’d won the first four races.”

Despite Senna making a clean sweep of 1991’s opening quartet, all at Woking could see the storm on the horizon.

“The Williams was a far better car,” says Robinson. “But they had a major gearbox problem.

“They didn’t know what it was. They were smashing gears. It turned out they were selecting two gears at the same time, because of their transverse box…”

McLaren’s lead driver ran out of fuel twice in 1991

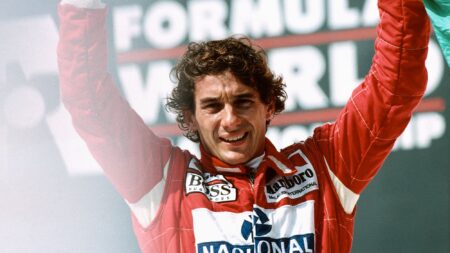

Senna would go out of ‘91’s fifth round at Canada with electrical issues, the first of five races without a victory.

Before that race he led the championship with 40 points, his closest challenger being Ferrari’s Alain Prost on 11 points, with Mansell on six points.

After the five-race lean spell, he had 51 points to Mansell’s 43, the Brit taking a hat-trick of victories in the meantime.

Among reliability and weight issues, Senna’s McLaren’s colleagues remember he would test their nerves with some daredevil lack-of-economy runs too.