Ayrton Senna, 30 years on from Imola

The death of Ayrton Senna was as massive a blow to racing as Jim Clark’s in 1968. Both were the clear yardsticks of their generation, though Ayrton’s occasional penchant for…

Left to right Ayrton Senna, Mike Nazaruk, Brian Shawe-Taylor, John Heath, Geoff Duke

Tomorrow’s date is May 1, 2024, which means that it will be exactly 30 years since the violent and untimely death at Imola of one of the very greatest racing drivers in the history of motor sport. The fine magazine/website for which I am privileged to write this weekly column has published and will doubtless continue to publish sad yet beautiful pieces on the subject of Ayrton Senna, and indeed Roland Ratzenberger, who was killed the day before, also at Imola; so I have decided to devote the 10 paragraphs that follow this one to four racers who, like Senna, also died on May 1. None of them is now remotely as famous as was and remains the great Brazilian, but each deserves to have his remarkable story told.

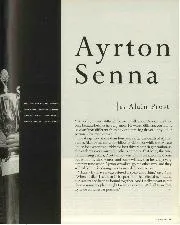

On May 1, 1955, in a sprint car race at superfast Langhorne Speedway, Mike Nazaruk was racing hell for leather, despite a nasty bout of flu, for that was the only way he knew how to conduct any automobile. He was running second, behind Charlie Musselman – what a name! – and the two men were not only among the finest and bravest sprint car and dirt track racers of the time but were also fierce rivals. Indeed, they had come to blows before. But there was grudging respect between them, for they were both World War Two vets, they were both hard men who knew what risking death looked like and felt like, and they were both categorically unprepared to give the other any quarter that day or any day.

Nazaruk overtook Musselman at Langhorne 69 years ago in what has been described by those who saw it as a hair-raising, heart-stopping, even spine-tingling move, then, little by little, he inched his way to a lead of about 100 yards (91.5 metres). A few laps later, perhaps distracted by a wild out-of-control moment for Ted Nyquist, or maybe laid so low by flu that he momentarily fainted – we will never know – he appeared not to slow or turn in as usual, his car hit the wall not once but thrice, one hard bang after another, then it somersaulted out of the stadium. Nazaruk was killed instantly.

Nazaruk leads in 1953 at the California State Fairgrounds

ISC Images & Archives via Getty

Ten years earlier, aged just 23, he had been demobbed, having fought with conspicuous courage in the infamously bloody World War Two battles of Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Guam, and Iwo Jima. When he then decided that only sprint car racing on dirt tracks could match the adrenaline rush of armed combat, the word that other drivers soon began to use to describe him was most often ‘fearless’. They were not wrong. In 1953 he had a god-almighty shunt in a sprint car race at the Minnesota State Fair. He would have been thrown clean out and some distance had not his left foot remained hooked into the pedal box, which meant that he was instead dragged like a rag doll from his still fast-moving wreck until it eventually came to a stop. He was taken to hospital, where his multiple wounds were extensively bandaged, and he was told to remain for a week-long rest cure. He refused, discharged himself, drove 600 miles (967km) to his home in Indianapolis, washed and changed, then drove a further 120 miles (193km) to Cincinnati, where he entered a 100-lap dirt track race for midget cars – and won it.

In truth he was not only fearless but also fearsome. He used to intimidate his rivals deliberately and aggressively, in the manner of prizefighters, staring them out and growling: “Don’t try to get between me and the chequered flag because, if you do, you won’t like what happens to you.” No wonder they called him Iron Mike, a soubriquet he earned decades before the ruthless and vicious boxer Mike Tyson ever did.

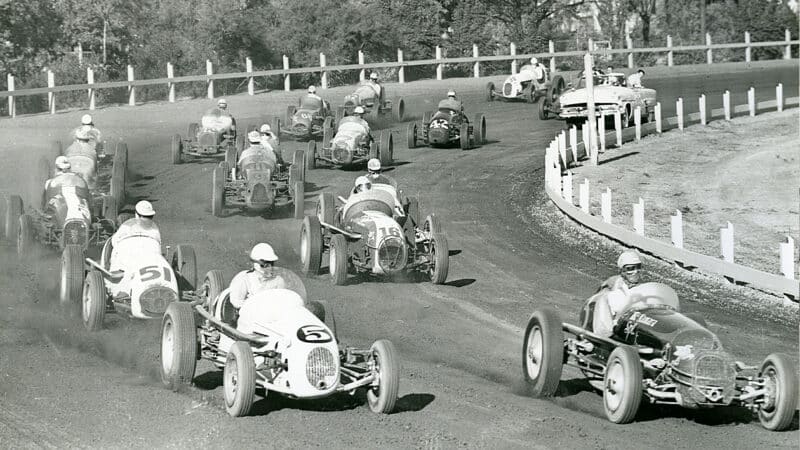

John Heath was a very different kind of cove. On April 29, 1956, almost a year after Nazaruk had met his maker, Heath was in Italy, competing in his second Mille Miglia, having raced a Jaguar XK120 to 40th place in the same event the year before. This time his ride was an HWM-Jaguar, and he had decided to tackle the 992 miles (1596km) on his own, with no co-driver. During the night it rained heavily, and two men lost their lives: first Ivo Badaracco crashed his Alfa Giulietta, killing his co-driver Max Berney, then Helmut Busch crashed his Mercedes-Benz 300SL, killing his co-driver Wolfgang Piwco. A couple of hours later, shortly after dawn, Heath ran his HWM-Jaguar too wide on a turn, tripping it over a fence and into a ditch. He was taken to hospital with broken arms, shattered ribs, and extensive internal bleeding. He fought the good fight for two days, but he died on May 1. He was 41.

John Heath in the fateful 1956 Mille Miglia

Alamy

Heath was a prudent racer rather than a flamboyant one, but his influence was significant. He it was who had founded Hersham and Walton Motors (HWM) in 1938. Then, after World War Two, assisted by his new business partner George Abecassis, also a racer, he moved the business to nearby Walton-on-Thames, 20 miles (32km) south-west of London. The two men raced the HWMs that they also designed and built, and they fielded cars for up-and-coming British aces, including Stirling Moss and Peter Collins. HWM exists still, on the same plot in Walton-on-Thames, as an Aston Martin dealer.

Like Senna, both Nazaruk and Heath lost their lives as a result of racing accidents. Like them all, Brian Shawe-Taylor breathed his last on May 1, but in his bed, in 1999, at the age of 84. Born in 1915, in Dublin, the son of Agnes Mary Eleanor Shawe-Taylor (née Ussher) and Francis Manley Shawe-Taylor, who was the Magistrate and High Sheriff of County Galway, at the age of five he moved with his mother to Shrewsbury, England, following the murder of his father by the IRA (Irish Republican Army).

Brian Shawe-Taylor suffered his career-ending accident shortly after this picture was taken, in an ERA at the 1951 Goodwood Trophy

Alamy

After World War Two, in which he had served in the Royal Artillery, he raced an ERA for a few years – and he lodged an entry for it for the 1950 British Grand Prix, the first ever championship Formula 1 race. His application was refused — the organisers told him that his car was too old and too slow — but he was determined to find a way to race in that historic event by hook or by crook and in the end he succeeded, by persuading his friend Joe Fry to let him share his Maserati, which Fry had qualified in 20th place. On race day they both had a go in it, finishing 10th, albeit lapped six times by Giuseppe Farina’s winning Alfa.

Shawe-Taylor was back at Silverstone for the British Grand Prix the following year, 1951, this time in a newer ERA than the one that he had unsuccessfully tried to race in the previous year’s event. He qualified it 12th and finished in the same position as he and Fry had achieved in their Maserati the year before – 10th – coincidentally also lapped six times by the winner, Froilan Gonzalez (Ferrari). Shawe-Taylor’s racing career came to an abrupt end when, in the 1951 Goodwood Trophy, in that same ERA, he crashed and was seriously injured. But he recovered and continued to prepare and repair racing cars at his Cheltenham garage for many years afterwards.

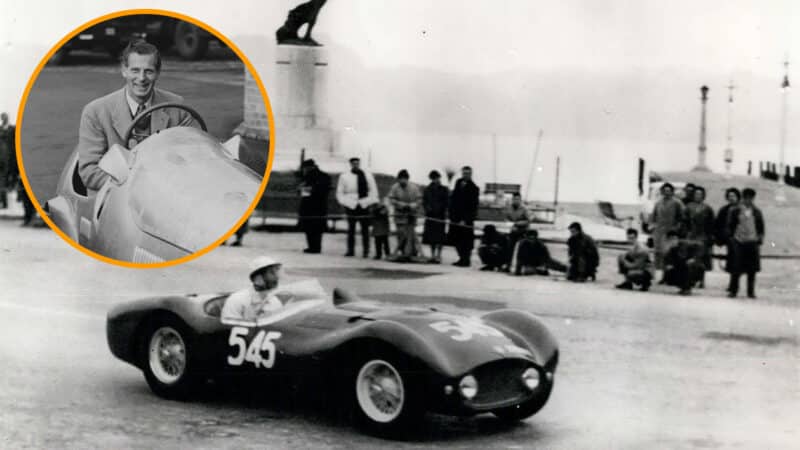

Did any other major racers die on May 1? I cannot think of any other drivers on four wheels; but riders on two wheels, certainly, yes, one of the very best. Lancashire-born Geoff Duke passed away peacefully on the Isle of Man, on May 1, 2015, aged 92, having previously won six TT races on the island on which he later made his home, and many more big motorcycle races besides. His send-off may not have been as extraordinary as that of Ayrton Senna, whose funeral was attended by three million mourners, was broadcast live on Brazilian television, and followed three days of state-sanctioned national mourning. But Duke’s cortege drove a whole lap of the long and legendary TT course, albeit at a fraction of the pace at which he had so often ridden it, so majestically, more than half a century before.

Geoff Duke on his way to victory in the 1950 Senior TT

Bert Hardy/Picture Post via Getty

The death of Ayrton Senna was as massive a blow to racing as Jim Clark’s in 1968. Both were the clear yardsticks of their generation, though Ayrton’s occasional penchant for…

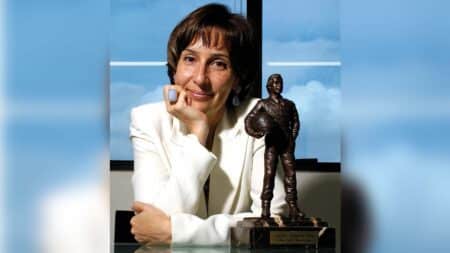

The Instituto Ayrton Senna was set up in the months after the triple world champion died at Imola in 1994. A small team of people led by his sister Viviane,…

It might not have won the 1993 Formula 1 World Championship, but nevertheless the McLaren MP4/8 holds a special place in the history of F1. Ayrton Senna’s last winning car,…

“Honestly, it’s very difficult for me to talk about Ayrton, and not only because he’s not here any more. He was so different, you know, so completely different from any other racing…

Thirty years on from a rain-soaked Donington Park, F1 still hasn’t seen anything like Ayrton Senna’s opening lap of the 1993 European GP. Matt Bishop remembers the magic

It seems to me appropriate – with May 1 upon us – to take a break from the current Formula 1 scene, from bickering about not enough noise and too…