But even so, he should by right have won a hatful of grands prix fully on merit. In fact had he enjoyed just average luck, he could have been the 1968 world champion for Ferrari. He was utterly brilliant, polished yet spectacular and technically in tune with the dynamics of a racing car in a way that had Ferrari’s Mauro Forghieri say of him: “Not only was he a driver of the calibre of Clark, but he was the best analyst of car behaviour of any driver I ever worked with.” Forghieri was at Ferrari from ’61 to ’86…

Amon, as a 17-year-old local driving an ancient Maserati 250F bought for £1,000, caused something of a sensation when the international stars turned up at the Levin track early in ‘63. He was among the quickest and his high-speed drifting technique drew gasps of appreciation. F1 team owner Reg Parnell sought him out. “Yeah, he said he’d never seen a 250F being driven like that since Fangio,” chuckled Amon years later. Parnell’s interest was Amon’s ticket into the European racing scene. He was on the F1 grid as a 19 year-old, the cars weren’t great but he was on his way.

Bruce McLaren saw something in Amon and recruited him to his burgeoning new team, and it was there his reputation as a test driver took hold as he completed thousands of miles of tyre testing for Firestone, the company which was largely funding McLaren at that stage. The tyre guys once played a trick on him, putting the same tyres back on they’d just taken off to see what he’d say. He came straight back in to ask if they were sure they hadn’t put the same set back on by mistake because they felt identical to the previous set. In later years Goodyear would be paying him even more than it paid Jackie Stewart.

Celebrating ’66 Le Mans win with McLaren

Motorsport Images

The Firestone link played its part in Ferrari calling for ’67 and as McLaren hadn’t been able to provide him with an F1 car because of engine supply issues, he left Bruce, though they did win Le Mans together. Forghieri had been able to create very good handling chassis for Ferrari but they were hamstrung by the ancient technology of their V12s, which were basically from the 1950s, trying to compete against the brilliant new Cosworth DFV. But they were good enough for Amon to become a contender.

In the period 1967-1972 Amon arguably delivered a greater quantity of virtuoso performances than anyone other than Stewart.

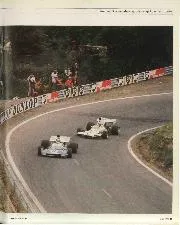

Mexico ‘67 was where Amon first got to go wheel-to-wheel with the great Jim Clark. “He was the best of us,” said Amon in retirement, “but I was able to have a brief nibble at him in Mexico and that precluded some fantastic ding-dongs with him in the Tasman series that winter.”