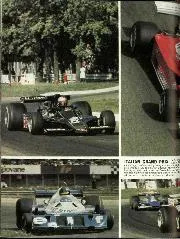

So who was quickest in free practice on Friday? Lauda, that’s who, the only driver of the 34 entered — yes, 34! — to deliver a lap that stopped the watches before 99 seconds had elapsed. Reutemann was next best, a quarter of a second behind. Having just taken the transparently opportunistic decision to announce that, unlike his team-mate, he would be continuing with the Scuderia for 1978, Carlos (second-quickest), rather than Niki (quickest), was the man whom the tifosi had cheered to the echo every time he had sped past.

As the qualifying hour began the next day, Reutemann was on it straight away, and his name topped the time sheets from the outset. Running him pretty close were the other four F1 drivers’ world championship contenders — Scheckter, Andretti, Lauda, and Hunt, in that order — but, with just two minutes to go, Reutemann was still on top, his beautifully fluent lap of 1min 38.15sec apparently unassailable. Scheckter had managed to get to within 0.14sec of him, Andretti was 0.22sec behind him, and Lauda trailed him by 0.39sec; Hunt was more than half a second in arrears.

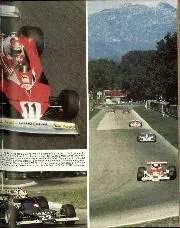

James had been uncomfortable all weekend, troubled by a sprained ligament in his right foot, sustained during a charity football match in Switzerland earlier in the week. At one point it had been feared that he might not be fit to compete at Monza, but on Friday morning he had found that his pain had lessened and his mobility increased. Now, on Saturday afternoon, still in some discomfort, he was on an out-lap, and, long regarded by the tifosi as a haughty irritant, albeit an undeniably rapid one, he fancied giving them a nasty surprise by having a crack at beating Reutemann, and to hell with the pain. He hustled his McLaren around the famous autodromo, and those who saw that now largely forgotten lap have told me that it was a banzai, white-knuckle, right-on-the-ragged-edge effort, the kind of lap that James would have described as “shit or bust”. As he crossed the line his lap-time was announced — 1min 38.08sec — pole position by just seven-hundredths of a second. Magnificent achievement though it was, both skilled and plucky, it was greeted with complete silence, for he had spoiled the tifosi’s fun. They never liked him, and he was undoubtedly a boozy playboy, but he was tough as well as raffish, and, when the mood took him, few F1 drivers have ever been more effective qualifiers than he was in 1976 and 1977.

Over a single lap, Hunt often proved formidable

Getty Images

When the race got underway the following afternoon, it was Scheckter who led, having made an excellent start from P3, passing both Hunt and Reutemann into the first chicane. However, second behind Scheckter was neither Hunt nor Reutemann but Regazzoni, who had qualified his Ensign seventh and, always a Monza favourite, knew fine well that if he got going a second-or-so early he would probably be allowed to get away with it. Third was Hunt, then Andretti, Reutemann, and Lauda. Hunt and Andretti both muscled their way past Regazzoni during the course of lap one, and Reutemann and Lauda followed suit on lap two. Andretti then nipped past Hunt, also on lap two.