Not everyone was sympathetic though. Denis Jenkinson in Motor Sport likened the stance to “saying climbing a Swiss mountain was more dangerous than taking a walk through the English countryside!” The spectators also had little audible sympathy.

Meanwhile the CSI, as the FIA’s sporting arm was then known, wasn’t much help. Even if you could find them. “The CSI men thought things through — and opted to scarper,” recalled Roebuck. “‘What is a safe circuit, anyway?’ said one of their number, Claude Le Guezec. So that was helpful.’”

Circuit officials on Friday promised overnight repairs yet, with five miles of two-tier Armco to sort, the task looked Herculean. And Jenks observed the circuit had but a “a small gang of workmen”.

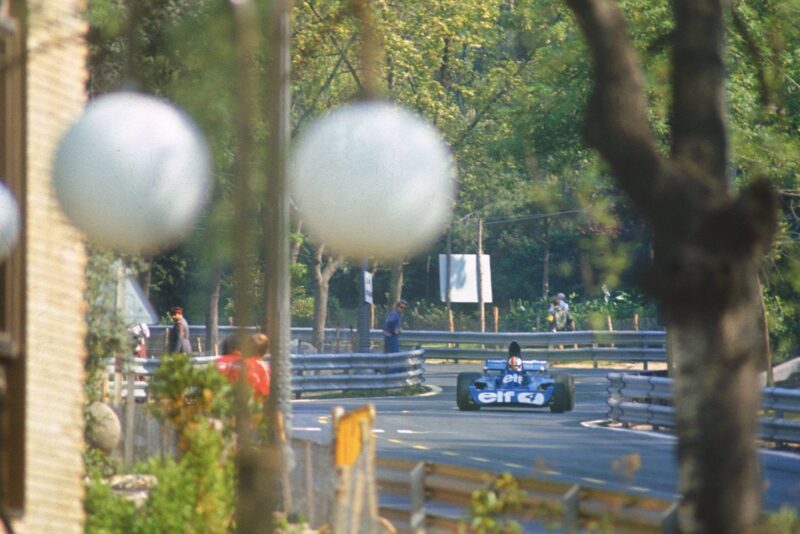

François Cevert, here in 1973, among the climbs and swoops of Montjuïch Park

Grand Prix Photo

Come Saturday things had indeed barely improved, so from midday the teams headed out to do the barrier repairs themselves. “The constructors and their work-force attacked the most crucial points on the circuit and the general feeling was that the circuit was 90% to CSI standards, and the FIA stewards accepted the circuit to be ready for racing,” said Jenks.

Then as Saturday afternoon drew on the local organisers chose the nuclear option. They gave the drivers a flat ultimatum: either the entrants’ contractual commitments would be honoured or there would be legal action.

This would mean the Spanish police impounding the teams’ equipment pending litigation. And the Montjuïc paddock was for the first time inside a derelict Olympic stadium which could be locked up within seconds.

The drivers’ unity, under pressure, dissolved. “Some team managers were making open threats of cancelling contracts or reducing the financial inducements,” Jenks reported, “while others went to the Texaco caravan [where the drivers were stationed] to drag their drivers out by the hair, or anything else they could grab hold of. The whole affair had become so sick it was no longer funny.

“One by one the drivers appeared in the pits, some with looks of relief on their faces, others looking very poker-faced, and last to appear was Emerson Fittipaldi who was greeted with whistles and cat-calls from the Spanish public in the grandstands.”