So it was that Dennis overruled Whitmarsh despite the latter having already verbally offered Perez a McLaren race drive for 2014. Checo duly sought and found refuge at Force India. It was a humiliation for Martin, whom I like and with whom I worked again at Aston Martin in 2021 and 2022, but it was clear that Ron wanted to regain control of his train set and would not be gainsaid. In January 2014 Whitmarsh resigned, and Dennis immediately restored himself as chief executive officer, appointing no-one as team principal but hiring Eric Boullier as racing director. Magnussen then drove superbly in the first grand prix of the year, in Melbourne, his F1 debut, qualifying fourth and finishing third on the road, which became second after Daniel Ricciardo’s disqualification for a Red Bull-Renault fuel-flow irregularity.

Since then Kevin has driven 162 further F1 races, starting from pole position once and posting fastest lap twice, but he has never again stood on an F1 podium. The most competitive F1 car he has ever raced was that 2014 McLaren, which was adequate at best. Since then he has raced one F1 season for Renault and six for Haas, never in a car that could in truth justify a description even as positive as ‘adequate’. Does he still have what it takes? Could he still shine as bright as he did in Abu Dhabi in 2012 or in Hungary in 2013 or in Australia in 2014 if by some twist of fate, at long last, he were to find himself in a race-winning F1 car? My answer to that question is yes, for I have watched him work miracles in racing cars in the past, but I admit that I am biased, because over the years he has become a proper mate. He attended my wedding in Soho (London) in 2015. He and his wife Lulu have stayed at my and my husband Angel’s Earlsfield (also London) house often. He and I have had dinner together dozens of times, all over the world. I have visited him in not only Copenhagen but also in less touristy parts of his beloved Denmark, once being driven by him flat-out at the dead of night from Aarhus to Copenhagen in a Honda Civic Type-R, a journey that resembled a grand prix not only in terms of distance (190 miles [307km]) but also in terms of skill and commitment. Despite his never having met my mother, he wept in front of me when in July 2013 I told him that she had died of cancer. And when, five years after we had stopped working together, I let him know that I had written a novel (The Boy Made the Difference; 2020) and that all proceeds would go to charity, he replied: “Well done mate, but I’ll never read it, because I’d never read a novel in English, you know that, don’t you?”

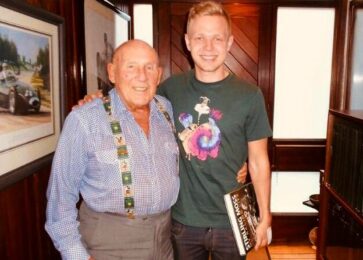

Matt & Magnussen on the road in Civic Type R

Kevin Magnussen

I did indeed know that, and it did not bother me at all. Some people like reading fiction. Others do not. Very few F1 drivers do. Still fewer enjoy doing so when the prose has been written in a language other than their mother tongue. Nevertheless, Kevin bought 50 copies, simply so that he could donate £500-odd to my designated charity, the Bernardine Bishop Appeal, which I had set up in memory of my mother and which fundraises for CLIC Sargent, a wonderful charity since renamed Young Lives vs Cancer. Heaven knows what he did with them all. (The Boy Made the Difference is still available on Amazon, by the way, and via other vendors too, if you are interested.)

Kevin Magnussen is a dear friend, as I say, and he is also a good person. He is a loving husband and father. He is a very experienced F1 driver, he is extremely fit, and his battle scars have made him not only wiser but also shrewder than he used to be; yet he is still only in his very early 30s. He is almost as embedded at Haas as Max Verstappen is at Red Bull. More’s the pity, perhaps. He could still win grands prix, and even F1 world championships, if the right opportunity were to knock. But, sadly, it almost certainly will not.