Written and directed by James Wiseman, this is a very well-crafted tribute to Mansell packed with wonderful archive curated by Wiseman’s prolific brother, Richard. The combination of Mansell’s perspective at the age of 69 and the gems unearthed here – many shown for the first time since they were first broadcast back in the day – makes this a film anyone a must for anyone who reads Motor Sport. Even if it’s too one-sided to be considered definitive history.

Wiseman has chosen Monaco 1992 as the kicking-off point, as Mansell darts left and right in his frantic chase of Senna following the pitstop for a suspected puncture that cost him a sixth successive victory. Immediately, there’s hyperbole: “Today Ayrton would have got a stop-go penalty for blocking,” Mansell tells us earnestly. Really? You sure about that? As Nigel admits, there was no contact between the Williams and McLaren. Didn’t Senna just park the bus fairly and squarely, as was his right? Straight away, then, we’re off.

We’re taken back to the beginning, Mansell recalling his humble Midlands roots and his lack of a “silver spoon” – and expressing himself nearly always in his characteristic ‘royal we’ perspective. The most revealing insight here is when Mansell describes how his father Eric broke a promise to support him into racing, causing a painful estrangement. Loyalty, trust and a sense of injustice were always key elements in the Mansell psyche.

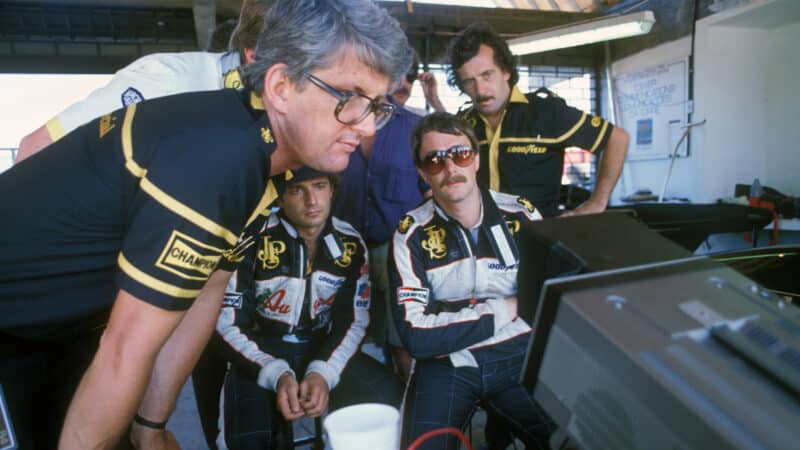

Peter Warr (left) didn’t rate Mansell, here with team-mate Elio de Angelis in Brazil, 1984

Grand Prix Photo

Although the focus is on his Williams years, the big break with Lotus and first F1 seasons are inevitably essential to the tale. A brilliant interview at home with Mansell during the Essex era, not long after his grand prix debut at the 1980 Austrian GP, is enjoyable and captures a young driver still trying to find his way. It’s entirely fitting that his first race should have pitched him straight into adversity, sitting in spilt fuel that caused second-degree burns – including to his “goolies”. Which other F1 drivers would use such a word? Priceless.

The mentor role of Colin Chapman is played up. Some within Lotus have suggested the relationship has been inflated beyond reality, but Mansell’s emotion seems genuine as he describes the devastation and consequences of Chapman’s death in December 1982. “I lost my father,” claims Nigel, starkly.

He also speaks openly about the hostility he faced from the late Peter Warr, whose antipathy towards Mansell isn’t really investigated. Why did Chapman’s lieutenant have so little time for him? Here, a voice to explore that perspective would have been welcome. Instead, we’re reminded of the nasty old “won’t win a grand prix while I’ve got a hole in my arse” comment, Mansell offering that Warr must be “constipated” given what followed at Williams – in the present tense, as if the bespectacled chief is still alive. It’s an odd moment.