Lunch with John Surtees

He knew what it took to win world titles like no one before or since – but if there was an easy route, this great man wouldn’t often choose it…

James Mitchell

John Surtees has always been a man to speak his mind. Whenever he joined a team, he would be determined to concentrate the focus of everyone around him on maximising the chances of victory – which, after all, was the point of the exercise. He was more interested in directness than diplomacy. He concedes that this did not always work in his own interests: but he was never prepared to accept any other way.

We all know that this man’s achievement in motor sport, becoming champion of the world on two wheels and then on four, is totally unique. Other great motorcyclists, like Geoff Duke, made the switch to cars but never found the same success. Some missed real greatness on bikes and then found it in cars, like twice world champion Alberto Ascari. It’s true that Tazio Nuvolari, European champion with Alfa Romeo in 1932, earned the European 350cc title for Bianchi in 1925; there have been others who have won on two wheels and then on four. But, in terms of the F1 world championship era, John Surtees stands alone.

John’s home for many years has been a beautiful Surrey manor house whose origins go back to medieval times. His choice of restaurant is a charming pub in Lingfield, The Hare, where he displays his no-nonsense taste by ordering fish and chips with mushy peas, and then apple pie. Accompanying this proper English meal is a glass of champagne. “We didn’t get it very often in my racing days. When we did we had a small swig, then shared it with the mechanics.”

John was born in 1934, and his beginnings, though humble, were steeped in the sport. His father Jack had a motorbike shop in Croydon, and raced a big overhead-cam 600cc Norton combination in grass-track events, with John’s mother Dorothy riding the sidecar. When John was 14 he rode the sidecar of his dad’s 1000cc Vincent in a race at Trent Park. “But when it got out that I was under-age we were disqualified.”

At 15 he left school to work in the shop, and then got an apprenticeship with Vincent. Soon he was preparing his own bikes for racing.

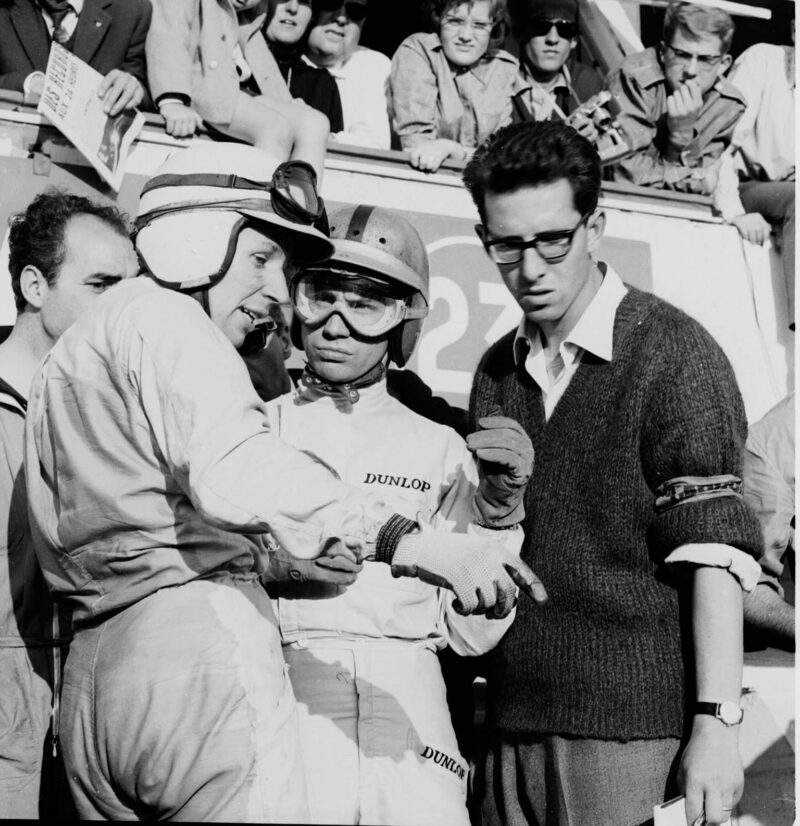

Racing for Lotus in F1, while also being a double world motorcycle champion in 1960

Motorsport Images

“I’d travel back and forth every day to the Vincent factory at Stevenage, and then work on my bikes all night. We’d travel to the races in our old van, me in the back with the bikes, wrapped up in a blanket to catch up on lost sleep.” His first road race was on a pre-war Triumph 250 at the newly surfaced, anti-clockwise Brands Hatch in 1950, when he was 16. Just as it began to rain John took the lead going into the uphill left-hander that we now know as Paddock Bend, and promptly fell off. “Then at Silverstone, going through Abbey Curve, the Triumph’s con-rod broke and it dumped me on my backside.” Next, with Jack’s help, John gathered together enough bits to build up a 500cc Vincent Grey Flash. With this, at the Aberdare Park circuit in South Wales, he scored his first win.

“Of all the races I did in my life, that was probably the one that had the most effect on me. For the first time I was no longer just a mechanic who rode a bike. The bike and I became one. We spoke to each other, we were exchanging messages through the seat of my pants. I realised that’s what you need to get the best from a piece of machinery. It shaped the mould for the rest of my racing career.”

The Vincent was replaced, with difficulty, with a Featherbed Manx Norton – “it cost £280, a huge sum” – and only the prize money that John was now earning allowed him to keep up his racing programme. Soon he was riding against and often beating the top racers of the day, always preparing his own bikes meticulously.

By the time he was 20 he was the big name on the British scene. In 1955, between April and October, his tally was 86 races and 70 victories – sometimes six in one weekend – plus a shoal of lap records. Riding a factory Norton he fulfilled an ambition by twice beating the works Gilera of triple world champion Geoff Duke, at Silverstone on Saturday and again at Brands Hatch on Sunday.

John longed to win the world championship on a British bike, but Norton curtailed its racing programme, and an approach to Triumph was rebuffed. “That sort of negative attitude was typical of the complacency in much of British industry at the time.” But Moto Guzzi, Gilera and BMW all showed interest, and then MV Agusta contacted him.

Team-mate with Mairesse at Ferrari in 1963. Forghieri listens on

Motorsport Images

“MV had had a disastrous time, losing two of their riders. Les Graham, Stuart’s father, was killed on the Isle of Man, and then the Rhodesian Ray Amm died at Imola. Late in 1955 – I was still 21 then – they flew me out for a test at Monza and Modena. There were wet leaves on the track at the Lesmos, and at Modena it was raining like hell. But I loved the silky high-revving power of the four-cylinder engines, and I signed.”

In the first four months of the 1956 season John did 16 races for MV and won 13 of them. His first world championship event for his new team was the Isle of Man TT. “They sent a couple of bikes over with their chief mechanic. We took them to St Pancras in our van, and put them along with our tools on the train to Liverpool. I sat with them in the guard’s van. When we got to Liverpool station we coasted them downhill to the docks and onto the ferry to Ramsay.” On the 350 John was leading when it ran out of petrol with 10 miles to go. On the 500 he won his first TT, and his first world championship race.

He went on to be crowned 500cc world champion that year, the youngest ever at 22. Over the next four seasons he won six more world titles for MV, and five more TTs. He left the lap record for that awe-inspiring 27-mile Isle of Man mountain circuit at more than 104mph.

“MV was just doing world championship events, so when I wasn’t racing for them I fielded my own bikes. I just loved to race, and I built a special AJS and a Norton for British events. But the press started to say, ‘Surtees doesn’t need an MV to win.’ Count Agusta said he couldn’t have that, and blocked me from racing any other bike. Well, that didn’t give me enough to do. And nothing in my contract said I couldn’t race cars on my free weekends.”

So in 1960 John lived an extraordinary double racing life. He continued to dominate the international motorcycle scene, ending up double world champion again on both 350s and 500s. Meanwhile, as soon as the car world realised that he wanted to race on four wheels, he had several offers. In the end, after playing himself in with a few Formula Junior and F2 races, he plumped for Lotus, and arrived in Monaco for his first Grand Prix in a works Lotus 18. The week before he’d been winning the French motorcycle Grand Prix for MV, but he seemed to have no difficulty in adapting to four wheels around Monte Carlo, although he retired with gearbox trouble.

He still had to fit in car races around his motorcycle commitments, so his second Grand Prix was the British at Silverstone. He finished in a headline-grabbing second place. A week later he was with MV at Solitude, winning the German motorcycle GP; but he also raced Rob Walker’s F2 Porsche at the same meeting. Next came the Portuguese GP at Oporto, and this time he led the race. At two-thirds distance he was half a minute ahead of Jack Brabham, but fuel was leaking from the tank over his legs. Eventually his petrol-soaked right shoe slipped off the brake pedal and he clipped the straw bales, pulling off a radiator hose.

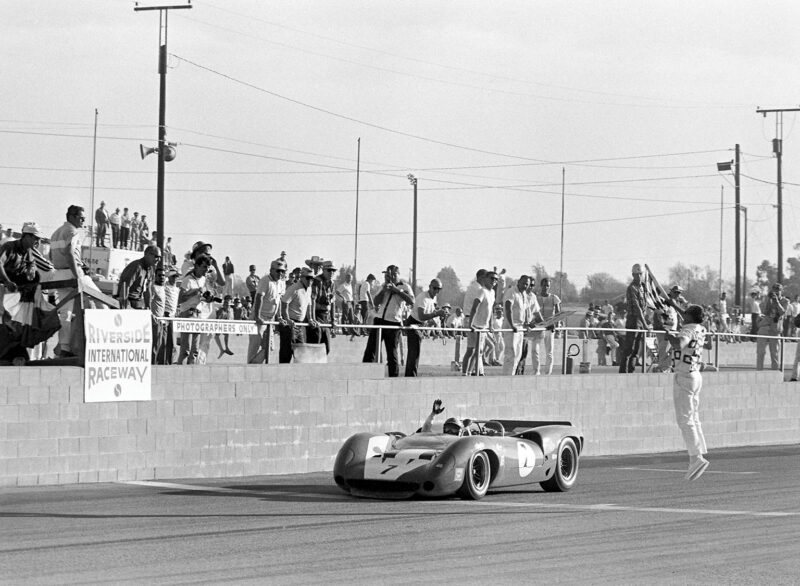

Another win leads to 1966 Can-Am title in a Lola T70

Motorsport Images

Not surprisingly his arrival on the four-wheel scene had created a sensation. “My bike experience was useful, in that I knew where some of the tracks went, but so much of the technique was different. What I could do unconsciously on a bike I had to think through in a car. That first year I didn’t really know what I was doing. I could go as quick as anybody, but I wasn’t particularly safe. I was very much on a learning curve.

“So I made some mistakes, a few on the track, but more off the track. Motor racing was quite a closed group then and, while some people welcomed me as a new boy, others resented it tremendously. Colin Chapman wanted me to be Team Lotus number one for 1961, and told me to choose my team-mate. Jimmy Clark was moving up from Formula Junior and had already done his first few Grands Prix, so I said I’d like him. Then all hell broke loose, because Innes Ireland was the contracted Lotus number one, and felt he was being pushed out. I didn’t want anything to do with all the politics, so I walked away from it. I was probably too sensitive; I should have stood my ground.”

So for 1961, the first year of the 1.5-litre F1, John spent a disappointing year in Reg Parnell’s Yeoman Credit Coopers, although he did win his first race for the team at the Easter Monday Goodwood. “For 1962 I had an approach from Ferrari. I flew out and saw the Old Man, but they already had five other drivers on the team, two of them Italians, and that sounded like more politics. So I said ‘No’. They told me, Ferrari doesn’t ask twice. But of course they came after me a year later.

“I knew Eric Broadley’s Lolas had beaten Lotus in sports car racing, so I suggested to Eric that he should build an F1 car. He got all enthusiastic, I did a deal with him for two cars, and then I went back to Reg and got him on board. So that was the two-car Bowmaker Lola team, with me and Roy Salvadori.

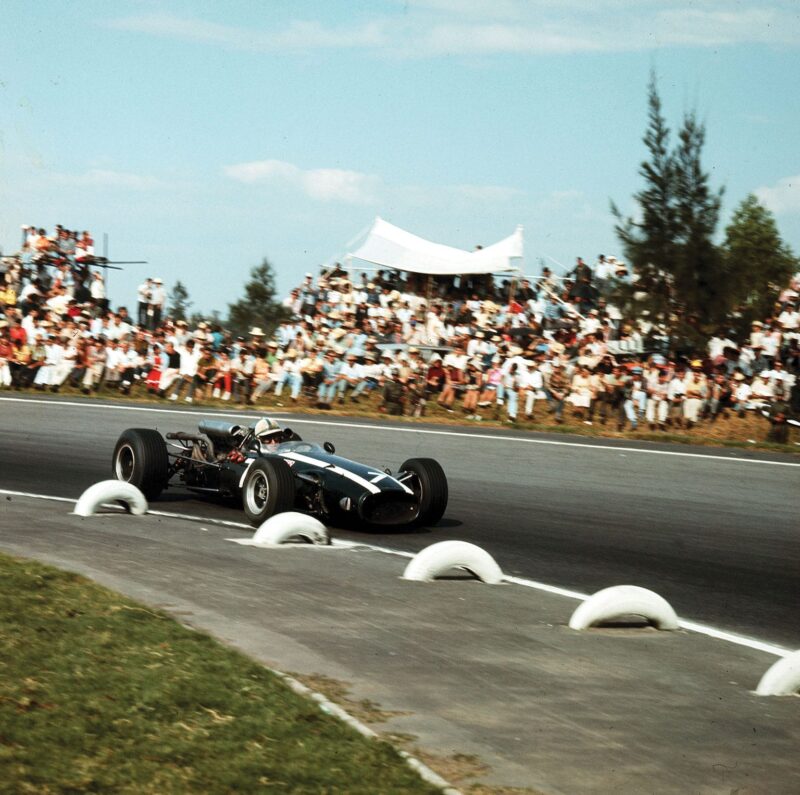

Victory in slight P3 at Monza, 1966, but storm clouds were on the horizon at Ferrari

Motorsport Images

“We now had the V8 Climax engine, and the car was steadily developed. I was second at Aintree behind Jimmy’s Lotus 25, and at the Nürburgring I was challenging Graham Hill’s BRM on the last lap, but got held up by a back-marker, so I finished 2.8sec behind him.

“I ended up fourth in the world championship. I put the Lola on pole for its first Grand Prix, at Zandvoort, but as I breasted a rise flat in fourth the front suspension broke and I tested out John Hugenholz’s catch-fencing. I always preferred the selective use of catch-fencing to the indiscriminate use of Armco barrier, and I haven’t changed my view. Armco has its place, but it’s not the answer for every corner, and for motorbikes it’s positively lethal.

“Then Ferrari wanted me again, and this time I signed. They’d had a very poor year in 1962, and the best time to join an Italian team is when it’s down. Of course it was sports cars as well as F1, which was great, except that it put F1 development right back, because nothing got done until after Le Mans. Hanging over the Old Man then was the double threat of Ford trying to buy Ferrari, and Fiat trying to take over, so he couldn’t afford not to take Le Mans seriously. And that’s where Dragoni came in.”

Eugenio Dragoni, Enzo’s direttore sportivo, had close links with Fiat, and he resented the direct relationship that John was building up with Enzo. “It was Dragoni’s little world, and I found it difficult to communicate with him.

I had to exert a bit of muscle to get things right, and I put in the occasional critical report about his decisions to the Old Man.

“We developed the new sports-prototype, the 250P, which was effectively the rear-engined V6 Dino lengthened to take a V12 Testa Rossa engine. I had a great time doing all the aerodynamic work at Modena with wool tufts and pouring oil over the bodywork to see how it flowed at speed, just as I used to do at the same track working on the fairings of the MV bikes. First race was the Sebring 12 Hours. Lodovico Scarfiotti was my co-driver, and we’d got the car set up as we wanted. The second, untested, car was for Nino Vaccarella and Willy Mairesse. But when we got to Sebring Dragoni decided that our car should go to them and we got the other car. I was so upset I nearly walked out there and then. I was packing my bags when Scarfiotti persuaded me to stay.

Own boss at last: Surtees wins 1970- Oulton Park gold Cup in TS7

Motorsport Images

“Among various other problems with the untested car, the rear bodywork wasn’t sealing properly and we were being gassed. Every time I came in to hand over to Lodovico I was sick as a dog behind the pits. But we won the race – except that Dragoni protested the result and said the organisers’ lap chart was wrong, and the other team car had won! Fortunately the lap chart done by my wife Pat, who was always perfectly accurate, coincided with the official one, and our win was confirmed. That was my first race for Ferrari.”

In the V6 F1 car that year John scored a brilliant win at the Nürburgring, setting a new lap record and beating Clark into second place – after the Lotus had been unbeaten for most of the season. It was his first Grande Épreuve victory. He was second in the British and third in the Dutch GPs, and in the 250P he won the Nürburgring 1000Kms with Willy Mairesse. At Le Mans he and Mairesse had a comfortable lead going into the 19th hour when the car burst into flames and was burnt out.

Then came his triumphant 1964 season with the now V8-powered F1 car: wins at the ‘Ring again and Monza, podiums at Zandvoort, Brands Hatch and Watkins Glen, and a magnificent drive in the final round in Mexico. Early problems dropped him to 13th place, but he fought back to finish second and take the world championship by just one point from Graham Hill. After Ferrari’s doldrums in 1962, it had taken John two seasons of hard work to put the team back on top.

“After my time with MV and now Ferrari, I had learned to like Italy, and I could speak the language reasonably well. The Old Man was several different characters in one, depending on his mood. At Maranello he was king, he’d act however he pleased. When you got him away from the factory he could be quite different. He had a little house down on the Adriatic coast, and sometimes he’d say to me: ‘Mare’ and we’d go off to the seaside, Pepino his chauffeur driving, the Old Man in the front, me in the back with the dog. Sometimes we’d be squashed into his Mini. He was a great admirer of Alec Issigonis, and told his road car people they should design a car with Mini-type suspension.”

At Le Mans in 1965 the works Ferraris hit trouble, but so did the Fords, and privateer Ferraris finished 1-2-3. “For the first half of the F1 season we were stuck with the V8, but what we should have done was concentrate on developing the flat-12. By Monza Maranello’s engine man, Franco Rocchi, had come up with new cylinder heads, and now it was the most competitive Ferrari I’d driven. It was flying. I put it on the front row alongside Clark, but coming round to the start the clutch went. I staggered off the line clutchless, and dropped to last. I worked back up to fifth, but then I couldn’t get any gears at all, and that was that.”

Flat-12 Ferrari 158 was a big advance in 1965, although Surtees retired at the ‘Ring

Motorsport Images

Meanwhile, with Enzo’s agreement, John had rekindled his relationship with Eric Broadley by running one of the new Lola T70s in Group 7 races. He won the Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch, and then his car and another for Jackie Stewart were flown to America for the autumn season, not yet called the Can-Am Series.

John’s schedule at that time was unbelievable. He was at Monza on Sunday for the Italian GP, flew straight to Canada to qualify the T70 for the St Jovite race on Wednesday, back to England for Friday practice and Saturday race in the works Lola T60 F2 car for the Oulton Park Gold Cup (which he won), then overnight back to Canada for the St Jovite race on Sunday (which he also won).

Five days later, at Mosport during practice for the Canadian sports car Grand Prix, he went out to try team-mate Jackie Stewart’s T70. “Flat-out past the pits a front upright broke. The car went off, and over and over.” He was dragged from the wreck with severe spinal injuries and a split pelvis, and bleeding profusely from ruptured kidneys. “When my condition stabilised I was mummified and flown to England. Once everything started to heal up, because of the damaged pelvis, I was four inches shorter on one side than the other. So my surgeon, Mr Urquhart, took one end and the senior registrar, a beefy lad, took the other, and they pulled like hell. They got the difference down to about half an inch, and it’s still that today.

“I was in hospital until the New Year, and I still had trouble walking when I went to Modena to test the new 3-litre F1 car, so the mechanics used an engine hoist to get me into the cockpit. My first race was the Monza 1000Kms a few weeks later, in the new P3 sports car with Mike Parkes.” It rained throughout and the P3’s screen wiper failed early in the race, but they won by over a lap.

But the 1966 Grand Prix season, the first run to the new 3-litre formula, did not start well. Ferrari’s new 312 was big and heavy, and the hefty V12 engine lacked power. “It was really just the sports car engine uprated a bit. I knew that the 2.4-litre V6 Tasman car would be quicker, particularly at Monaco, but the big engine had to be used, to boost the reputation of Ferrari’s V12 road cars. I scrambled it onto the front row and led Stewart’s 2-litre BRM until the diff seized – but Lorenzo Bandini was second in the 2.4 V6 Ferrari that I’d wanted to drive.

After his Ferrari split he drove a Cooper-Maserati, giving the car its first win in Mexico in 1966

Motorsport Images

“Next came Spa, where the weight handicap wasn’t so significant, and Rocchi had squeezed out a bit more power. I followed Jochen Rindt’s Cooper-Maserati in the rain, biding my time, and then went ahead and won the race. All I got from Dragoni afterwards was. ‘Why did you let a Maserati stay in front of a Ferrari?’ I said, ‘I’m in the car, I drive the race.’

“A few days later we were at Le Mans. I said to Dragoni: ‘The Fords are being driven by real racers – Gurney, Andretti, Amon, McLaren – and the only way we’ll beat them is if I go flat out from the fall of the flag and try to break them.’ But when Dragoni heard that Gianni Agnelli, the head of Fiat, was coming to watch the race, he decided that my co-driver Scarfiotti – who was not only Italian but was actually related to Agnelli – would drive from the start.

I reminded him that I was faster than Scarfiotti, but Dragoni was immovable.

“For the second time in my career I was perhaps a bit quick on the boil. I jumped into my 330GT road car and drove flat out, there and then, to Maranello, and went straight in to see the Old Man. I told him I’d joined Ferrari to win races, not to get involved in politics. That was our divorce.” John drove back to England no longer a Ferrari driver: Ford finished 1-2-3-4 at Le Mans, and Ferrari was soundly beaten.

“I’d expected to see out my career at Ferrari, and I’d moved into a little flat in Modena. But at once Roy Salvadori, who was managing the Cooper-Maserati F1 effort, was on the phone, and I agreed to join as Rindt’s team-mate. I flew straight back to Modena to see Alfieri at Maserati, and ask for some mods to their V12 based on what I’d learned up the road. And I didn’t miss a single Grand Prix.”

In his first Cooper outing, the French GP at Reims, he split the Ferraris on the front row – which must have pleased him – and led the race briefly before a broken rotor arm stopped him. He finished a magnificent second at the ‘Ring, despite losing two gears, and at Monza he ran in the leading group until the fuel tank ruptured. At Watkins Glen he had to pit after being spun round by a backmarker, but he came back brilliantly to finish third, breaking the lap record. Finally in Mexico he took pole position and led almost all the way to victory. He’d finished second in the world championship, and elevated Cooper to third in the constructors’ championship – just one point behind Ferrari…

Thoughtful at Monaco in 1964

Motorsport Images

“While I was doing all that I was also running my own Lola T70, under the banner of Team Surtees, in the new Can-Am Championship – just me and my mechanic Malcolm Malone in a one-man-and-a-van operation.” John won three of the six rounds and took the Can-Am title ahead of Mark Donohue and Bruce McLaren – plus about $70,000 in prize money, more than if he’d won every Grand Prix that season.

“Now comes a big chapter: Honda. They’d been in F1 for three seasons with Ronnie Bucknum and Ritchie Ginther, but in Mexico Yoshio Nakamura came to me and said, ‘We’re going to stop racing unless you join us. We want you to find us a location in England and help us do things right.’ If I’d just focused on what was best for John Surtees, racing driver, I should have gone to one of the established teams. But I always get enthused by challenges.

“We set up in our unit at Slough, just around the corner from Lola, and I found Honda’s engineers a flat in town. But the car was enormously heavy, not helped by an engine based on a pre-war Alfa Romeo design with roller bearings, centre power take-off and three-shaft gearbox. Then mid-season I had the idea of saving weight by going to a Lola Indianapolis monocoque. Nakamura got the OK from Honda, and we got drawings off to Tokyo so they could machine all the bits out of titanium, to compensate for the weight of that huge engine. The car was finished a week before the Italian Grand Prix. We got it to Monza, and I sorted out Jack Brabham on the final lap to take victory by a fifth of a second.

Debut victory for Honda RA300 ‘Hondola’ at Monza 1967

Motorsport Images

“For 1969 we built a car in England ourselves, and Honda updated the engine as much as possible.” John got second place at Rouen and easily led at Spa, setting fastest lap, until a rear suspension bracket broke. But meanwhile Honda had decided to follow a parallel programme with an air-cooled car. “I’d been promised a new V12, lighter, more compact, with plain bearings. But they made a commercial decision to help publicise the N600 air-cooled production car. I knew nothing about it until this weird looking thing appeared, covered in scoops, with an air/oil-cooled V8. I tested it at Silverstone and Monza, and the car itself wasn’t too bad, but after a few laps the engine always overheated and blew out all its oil.

“I said I wouldn’t race it, but people at the top of Honda said it had to appear, so Jo Schlesser was brought in for the French Grand Prix at Rouen. On the second lap he crashed and was burned to death. His accident killed the whole race programme stone dead. We finished the season, and I got third at Watkins Glen, and then Nakamura came to me and said, ‘John-san, it’s the end.’ Once again I was without a drive.

“So I accepted a seat with BRM. I had great respect for what they’d achieved with their 1.5-litre, which was a quick, reliable little car, and their 3-litre V12 seemed a good straightforward engine. But I’d reckoned without the Louis Stanley situation. We’d have a meeting, Sir Alfred Owen would be there, we’d make some firm decisions about the way forward. Next thing I’d get one of Stanley’s phone calls in the middle of the night: ‘Now my man, we don’t really need to do that, do we?’

“There was a lot more of that sort of thing. I felt sorry for Sir Alfred, but Stanley was his sister’s husband and it seemed he couldn’t interfere. Despite huge efforts to improve the car, I had a miserable season.

“Meanwhile I agreed to run in Can-Am for Jim Hall’s Chaparral team in their weird 2H. It had a very narrow rear track, huge tyres, and a horizontal screen that was almost impossible to see through. After three races I walked away from that. By October I was feeling tired and ill, and just after I’d managed to carry the BRM into third place at Watkins Glen I was diagnosed with viral pneumonia. Lying in hospital and looking back over Lotus, Ferrari, Honda and BRM, I decided I was not going to be dependent on other people any more.”

As Team Surtees, John had been running David Hobbs and Trevor Taylor in the 1969 season of Formula 5000 with his own car, the TS5, an adaptation of a Len Terry design. Taylor was runner-up in the European F5000 series, and Hobbs also did very well in Formula A in America. Encouraged by this success, John decided to become a Formula 1 constructor. He set up with a small staff in new premises in Edenbridge, Kent, and his first F1 car, the TS7, was ready by mid-1970. In Canada John scored the first world championship points for the Surtees marque.

For 1971 he was backed by the veteran F1 sponsor Rob Walker, in conjunction with Brooke Bond Oxo. High spot was victory in the non-championship Oulton Park Gold Cup, and he ran third in the German GP until his engine failed four laps from the finish. A second works car was run for Rolf Stommelen under a German sponsor’s colours, and in a third car fellow former biker Mike Hailwood had a sensational run at Monza. In his first Grand Prix for six years Mike finished fourth, right in the slipstreaming lead group just 18/100ths of a second behind winner Peter Gethin.

For 1972 John ran Hailwood and Tim Schenken in F1, and also put together a highly successful Formula 2 team, sponsored by Matchbox, which gave Hailwood the title of European champion. John himself won the F2 Japanese Grand Prix at Mount Fuji and at Imola. Then, after a one-off drive in the Italian GP at Monza, he hung up his helmet to concentrate on team management.

Team Surtees continued in F1 with Mike Hailwood, Jochen Mass, Carlos Pace, John Watson and others through to 1975. In 1973 Pace was fourth at the Nürburgring and third at Zeltweg, setting fastest lap in both races; and Mass was runner up in that year’s F2 series. But 1974 was blighted by a disastrous sponsorship deal with the Belgian arm of hi-fi manufacturer Bang & Olufsen. “The son of the man who ran B&O Benelux was Bernard de Dryver, and we agreed to give him an F2 test. We went to Goodwood, sent him out, and he came back in with the car all stuffed with grass. I said, ‘He’s not made out to be a racing driver. I don’t want to take the responsibility of running him.’ So his old man cut the money off. I fought him in the courts for breach of contract, but in the end I couldn’t afford to keep pursuing it. All we got was our costs, and ultimately that was what brought my team to an end.

“While we were still fighting that, we got sponsorship from the London Rubber Company, who made Durex condoms. We ran Alan Jones in the 1976 Surtees TS19 and first time out, at the Race of Champions, he got second place. Because of our sponsor’s product the BBC withdrew TV coverage of the race, which gave Durex lots of publicity. They ran an ad campaign which showed our Surtees TS19 with the tag line: ‘The small family car.’

“We ran Vittorio Brambilla in 1977 and ‘78, and when he was injured in the Italian GP start-line accident we hired René Arnoux. René was like a breath of fresh air, so enthusiastic. But when he had an offer from Renault I told him he should take it.

“I was back in hospital then, with serious problems that were finally traced back to a blood transfusion I’d had 13 years earlier after my Canadian accident. I’d enjoyed running the team and the cars, but not always being on a shoestring, never being able to do things the way I wanted. I thought it through, and I decided to finish with F1. I sold my FOCA membership to Frank Williams.

“In 1979 Pete Briggs, who’d been with us on the F1 and F2 teams, ran a couple of TS20s in the British Aurora Championship, and Gordon Smiley’s victory at Silverstone that October was Team Surtees’ last ever race. During the life of the team we’d sold a lot of cars as well: in all we built some 100 chassis.

“I didn’t want to know about cars after that. I restored a number of bikes, I did a fast demo lap at the TT on a five-year-old MV, and then I got back onto four wheels showing Mercedes’ museum cars around the world. I married Jane, whom I’d met when she nursed me in hospital in 1978, and we had two girls, Edwina and Leonora, and then in 1991 a son, Henry.

“I didn’t push Henry towards motor sport, but when he was eight years old a friend took him to watch karting at Buckmore Park, and when he got home he said, ‘Daddy, that’s what I want to do.’ So Jane would go off at weekends with the girls and the horsebox, and I’d go off with Henry and the kart, as mechanic, chauffeur and mentor. As we set off each weekend, he’d say, ‘We’re off on another adventure, Dad’.”

Henry did well in karting, and at 15 he moved up to Ginettas, winning second time out at Snetterton. He moved on to Formula BMW, and was runner-up Rookie of the Year. In 2008 he ran in Formula Renault, and also had his first Formula 3 outing at Donington, finishing first and second in his two races. Clearly, Henry Surtees was a bright new motor-racing talent.

For 2009, now 18, he ran in the first year of the relaunched Formula 2. On the Saturday of the July Brands Hatch weekend he scored his first F2 podium. On Sunday another car crashed into the tyre wall at Westfield. Its left rear wheel bounced back across the track in front of Henry’s car, and in a thousand-to-one chance hit his helmet face on. Henry died later that day.

It is impossible to comprehend the effect this dreadful tragedy had, and six years later continues to have, on John and his family.

At Henry’s funeral John asked for contributions to Headway, the head injuries charity, instead of flowers. “Nearly £35,000 was given, and I thought, I’m going to continue with this. So the Henry Surtees Foundation came into being.”

Driven by John’s inexhaustible energy and dedication, the Foundation’s far-reaching projects have included work in education, air ambulances, a new blood transfusion service, medical training, providing ‘brain chairs’ to help rehabilitation, and notably helping young people to find work in motor sport and the motor industry. “Not as drivers, but real jobs, careers. We use the emotion of the sport to pull them away from their screens and computer games.” As part of this process John has recently taken over Buckmore Park, the circuit where Henry first saw kart racing. Fund raising events are run at Buckmore, like the big Henry Surtees Challenge for kart and car racers this October 7, and also at Brooklands.

I ask, diffidently, if the way John has thrown himself into the work of the Foundation has done anything to help the healing process following the tragedy of Henry’s loss. At the lunch table everything goes quiet for a few moments.

Then: “Nothing can heal that. No, nothing.”

John’s racing life, ever since he first rode his father’s sidecar in 1948, has been a roller-coaster of changing fortunes. It has encompassed victories, bitter disappointments, championship titles, and now tragedy.

But through it all John’s loyalty to his own principles, and his determination to speak the truth as he sees it, have never wavered.

This is an extraordinary man.