“Chapman would just walk in and draw all over it!

“He’d sort of look at you, grin and laugh – because he was always laughing – and then just disappear out the door! Everyone would just look at each other and go ‘Oh, f***!’”

“He’d go off to the car factory and see if he could get them out of the mire – because they always seemed to be in it – then he’d come back to us at 5pm and do it all over again. He was a very impressive bloke – but infuriating. You always had to be on your guard, it was a total madhouse.”

Things began to pick up with a podium for Gunnar Nilsson at Jarama, but Southgate says Chapman enjoyed making things interesting at the track as well.

“Chapman would insist he wasn’t a gambler, but he was always betting. he engineered Mario Andretti‘s car and I engineered Gunnar’s. He would always bet me his race car would have less fuel in it than mine – at every bloody race.

“I’d calculate a safe amount of fuel, but Chapman would also always put in the minimum. The boys started adding a ‘mechanic’s gallon’ to his to make sure it didn’t go dry, but then he found out and just started factoring that into his calculations!

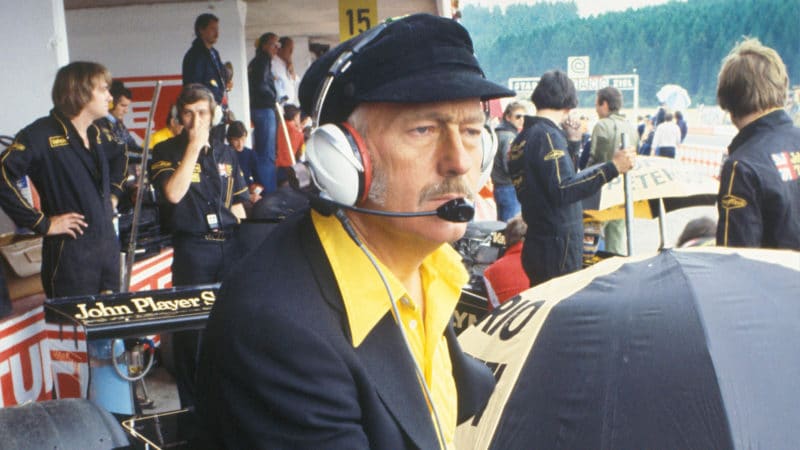

Southgate – standing in centre with brown jacket – over Gunnar Nilsson’s car at Zolder in 1977

Grand Prix Photo

“The idea of my car running out was pretty grim, but he was the boss so could do what he liked. The lads said he did run out once…”

So competitive was Chapman, he even found himself rooting against his own team: “We beat him on pitstops once, and he came up to me saying ‘I don’t know how you did it, but I’ll accept the result,’” laughs Southgate.

Once the team made it back to base, the capers didn’t stop there.

“We’d already have a handwritten work list by the time we got back from the race,” Southgate remembers. “Chapman would fling things at you and I’d actually do the majority of it.

“You haven’t painted my wing?! I don’t want that scruffy wing on my car!’”

“Typically there’d be 80 items, and to give you an example one of these items would be ‘new front geometry’ Ha! Not little things.

“After one particular race, he’d written ‘Paint the rear wing’. We were really pushed for doing all the jobs in the turnaround before the next race, and we didn’t do it.

“He came rushing in when we were still putting the cars back together and I admitted the wing hadn’t been repainted. ‘What d’you mean it hasn’t been painted?! You haven’t painted my wing?! I don’t want that scruffy wing on my car!’

“So he picked it up off the floor, and threw it across the workshop. It bounced on the floor and slid till it smashed into the wall, and he stormed off.

“We just picked it up laughing, now with even more scratches and dents on it, and put it back on the car. That was a typical kind of incident which would happen all the time.”