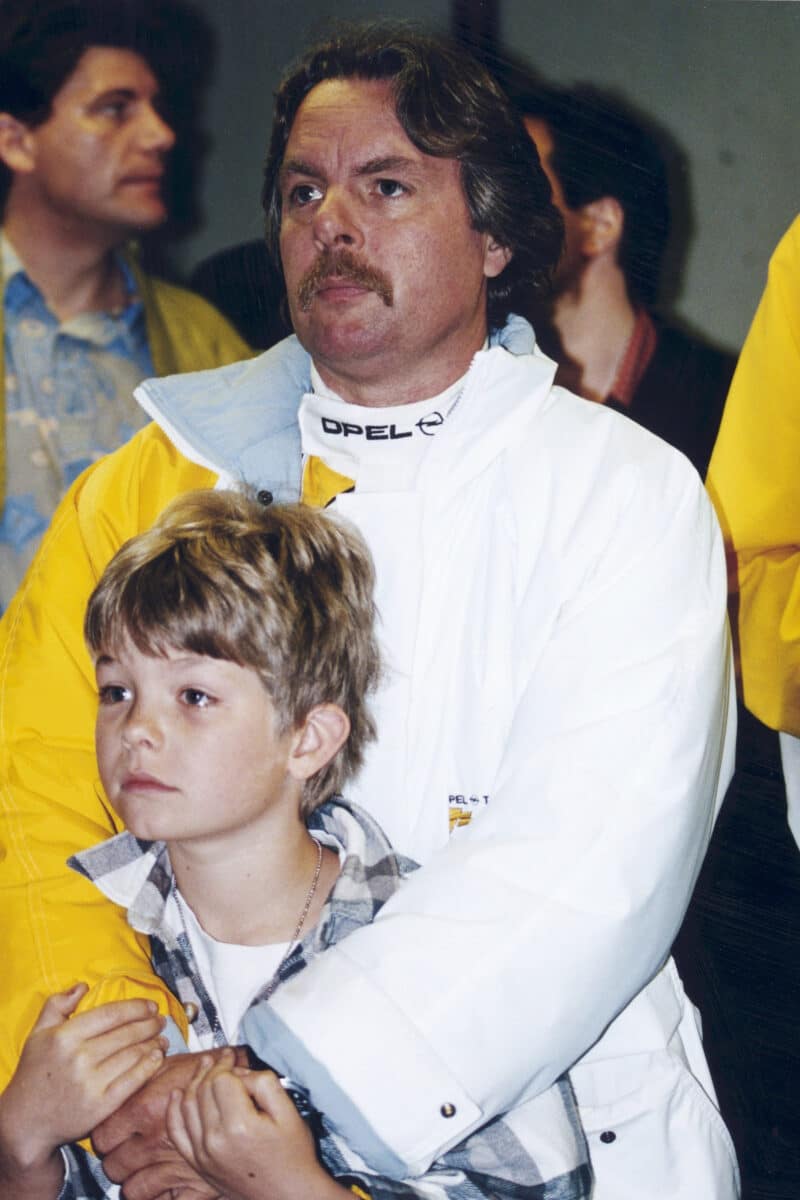

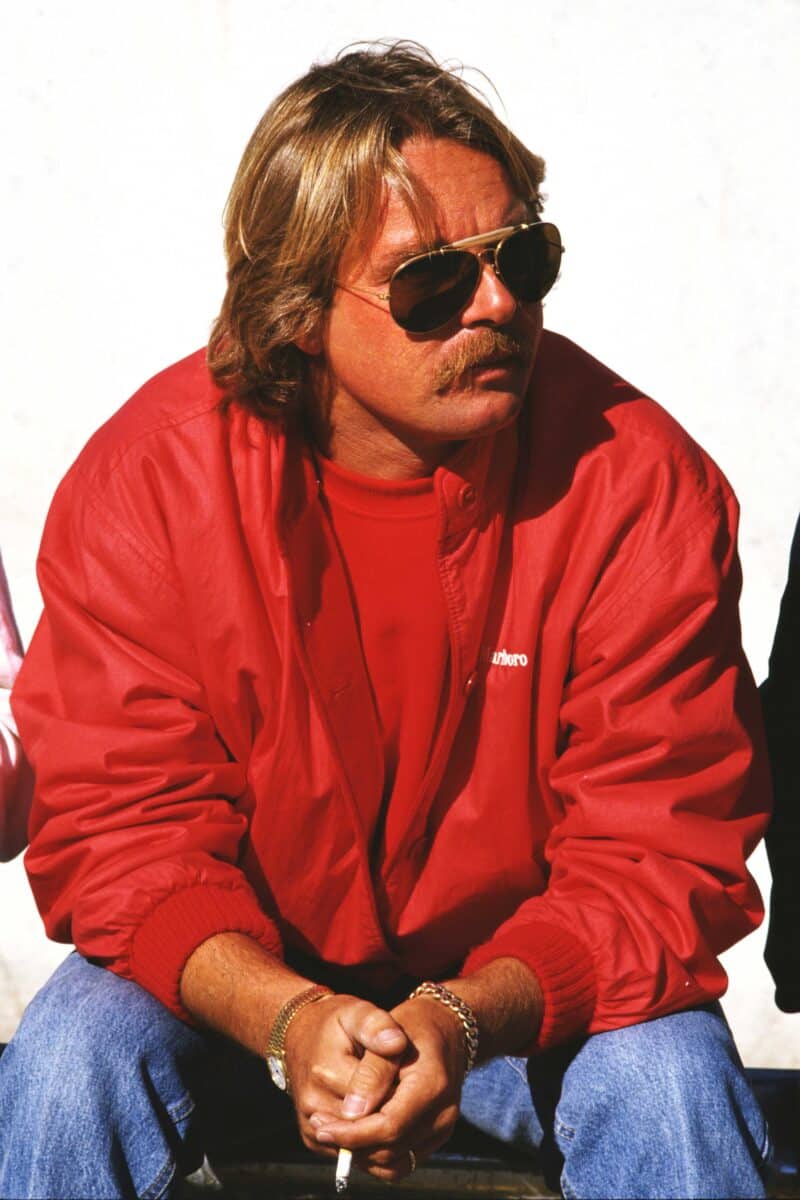

Rosberg was a drivers’ driver. A trailblazer – F1’s first ‘flying Finn’ – he was also majorly cool in a ‘Come to Marlboro country’ kind of way. He looked more like a NASCAR good ol’ boy than an F1 superstar – shoulder-length hair, bushy moustache, ever-present Ray-Bans, cigarette almost always on the go – and, born in Sweden but raised in Finland, he also had something of the Viking warrior about him.

The fiercest Viking warriors, those who fought in a trance-like fury, were known as berserkers, which is where the English word ‘berserk’ comes from. Rosberg drove a bit like that in his early days – opposite-locking, kerb-hopping and jitter-bugging his cars to sometimes improbable lap times. In Formula Vee, Formula Super Vee, Can-Am, Formula Atlantic, Formula Pacific and Formula 2, he was often ragged and usually fast, sometimes very fast, and he frequently shone when caution needed to be thrown to the wind: for instance in the wet and at the Nürburgring Nordschleife. Running in F2 as a privateer entered by driver turned wheeler-dealer Fred Opert in 1978, and by arriviste garagiste Ron Dennis in 1979, he was rarely able to compete with the works March-BMWs, which had it all their own way in 1978, or the works March-BMWs and Toleman-Harts, which dominated in 1979. Yet, in both those years, he was mighty at the old ’Ring. In 1978, in Opert’s Chevron, by no measure a match for the new and all-conquering Marches, of which there were 16 in the field, he qualified second, beating 15 of them. The following year, 1979, now in a Dennis-run March, he blitzed qualifying to win the pole by a scary margin: 4.5 seconds. A month later James Hunt retired from F1 in mid-season, and his Wolf team snapped Rosberg up. Keke was on his way.