Barnard had just come off a stint penning a ground-effect IndyCar for Jim Hall’s Chaparral team, the 2K, which would go on to win the 1980 Indianapolis 500 with Johnny Rutherford at the wheel. Furthering that aerodynamic advantage in F1 would ultimately lead him to his eureka moment.

“The thing was then we were all looking at ground effects in the underbodies on our cars,” he explains. “Having done the Chaparral, I could see there was obviously a lot of work to do under the car, one of them being to get a bigger underbody and therefore a better underwing.

“One of the issues was the chassis which needed to be very narrow, and that inevitably, would have lost torsional strength and bending stiffness, things like that. So I started thinking how I would make a chassis that would could be narrow and yet maintain all those other elements.”

A steel-skin monocoque was considered and then dismissed as being too heavy, but by then the idea of a carbon-fibre composite design was already percolating in Barnard’s brain.

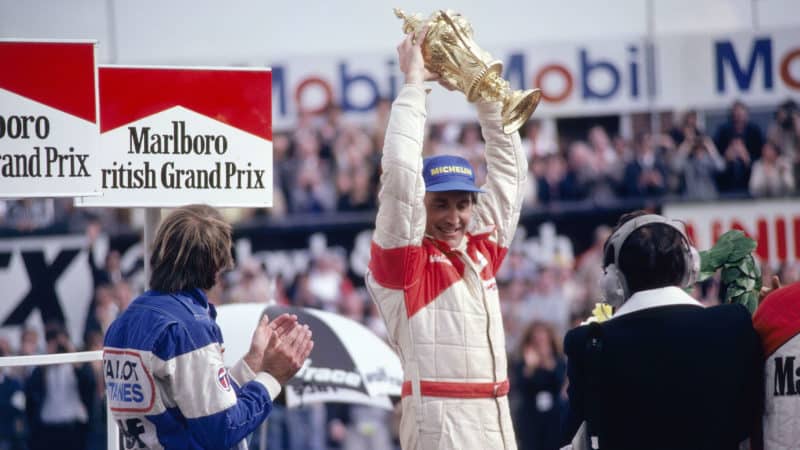

MP4/1 is readied for Argentina debut

Grand Prix Photo

The seed had been planted after seeing Embassy Hill reinforce wings with carbon-fibre (failing with tragic results at the 1975 Spanish GP) and a number of Gordon Murray’s Brabhams had carbon fibre panels in lightly loaded areas.

However, a day trip on a fact-finding mission would soon encourage Barnard to go the whole hog.

“I got the invitation to go and look at British Aerospace at Weybridge,” he recalls. “They were making the Rolls-Royce RB211 engine outer-cowling which was a carbon fibre–aluminium honeycomb sandwich.”

Wandering around the facility, it began to dawn on Barnard that he might have just found the material he was looking for.

“There were two things that happened,” he says. “Looking around the works at Weybridge, I went into this little room which there was one guy working in there. There were just bandsaws and vertical drilling machines. Nothing special, just the usual kind of stuff you’d find in more or less any workshop.