“James was a highly competitive person,” he says. “He was intelligent and had worked out if he had the inside line going into Tarzan and you were on the outside, he would sweep up the track and essentially drive you off the track. I backed out of it. Mario Andretti believed James understood the etiquette of racing wheel to wheel to give racing room – and James didn’t.

“With respect, he lucked into his title [because of Lauda’s Nürburgring accident], but he made the best of what was offered to him. In Canada and America he was the dominant driver in an excellent car and the team understood how to get the best out of him. As he went into 1977 he had the benefit of being the world champion and felt ‘I can do it again’ – fundamentally he was outstanding then.”

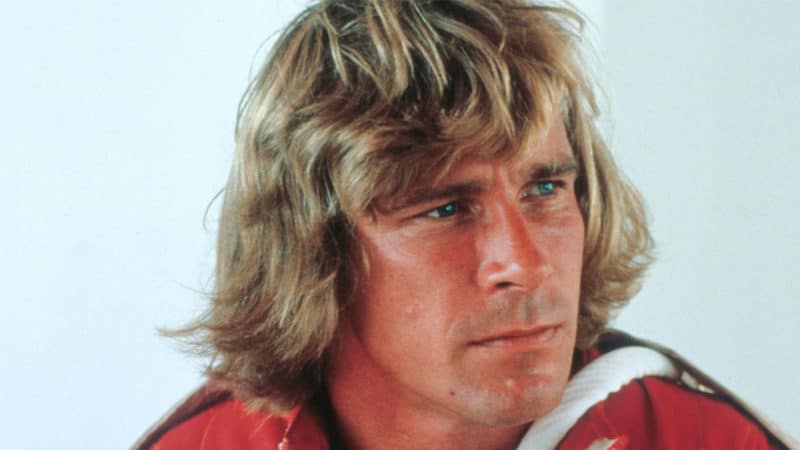

Another competitor to witness the man and racer up close was Hunt’s McLaren team-mate Jochen Mass. The two got on but, as the German admits, the ’76 champ would do what he had to in order to win.

“James was wild,” says Mass. “He never calmed down completely and I think there was a reckless streak that came between him and his well-being.

As success waned, so did Hunt’s interest in staying an F1 driver

McLaren

“As a driver he was masterful and brave. When he came to McLaren from Hesketh he was used to a one-car team, getting his own way, so he covered his cards, never gave anything away. I liked him, there was a mutual respect.”

That steely exterior forged at Hesketh was something appreciated by his first F1 team boss, helping the little outfit to become a front-runner for a brief period.

“If he’d been born 20 years earlier he would have been a fighter pilot”

“James was not only a quick racing driver, he was also tough; extremely competitive,” says Lord Hesketh.

“If he’d been born 20 years earlier he would have been a fighter pilot. There would have been a lot of black crosses on the side of his Spitfire. He had no time for the celebrity thing. It really didn’t interest him.”

Hunt’s darker side and increasing fear of risking his life for anything other than a win ultimately led him to quit halfway through 1979.