Jacques Laffite: My Greatest Race

Argentinian Grand Prix, Buenos Aires, 1979 I’ve always considered Argentina in 1979 to be my first real Grand Prix victory. I’d won in Sweden in 1977, but only because of…

Laffite with Ligier JS11 designer Gérard Ducarouge at 1979 French GP

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

In April 1976 I attended a Formula 1 test at Brands Hatch. It was a Goodyear tyre session rather than an official test and, although I can find no record of it online, I remember almost everything about it. When you are 13, memories like that stay with you for ever. So I can tell you now, 47 years later, that Jody Scheckter was driving a Tyrrell P34, Tom Pryce a Shadow DN5B, John Watson a Penske PC3, Jochen Mass a McLaren M23, Gunnar Nilsson a Lotus 77, Clay Regazzoni a Ferrari 312T and Jacques Laffite a Ligier JS5. There were not many fans present, what few there were could mill about in the pitlane, and most of that milling about was centred on the Tyrrell garage, for the P34 had six wheels and had never yet been driven in a grand prix. We could also stand trackside, watching and listening.

Yes, listening. The Tyrrell, the Shadow, the Penske, the McLaren and the Lotus were all running Cosworth DFVs, which magnificent V8 engine was nine years old by then and was good for 10,500rpm and 485bhp, channelled through a Hewland manual gearbox. Heel-and-toe downchanges were required and, let me tell you, those cars sounded splendidly guttural on the overrun as Scheckter, Pryce, Watson, Mass and Nilsson blipped their throttles to rev-match under braking.

Regazzoni’s Ferrari had a flat-12 engine that revved to 12,500rpm and pumped out 500bhp. It sounded even better than the Cossie-powered cars but, when it came to aural ferocity, the Matra V12 in the back of the Ligier ruled the reverberant roost. It, too, was a 500bhp motor, and at its 11,800rpm red line it screamed like a banshee. “Just listen to that cultured howl,” an old man said to me as we were watching at the exit of Surtees and together saw, and heard, Laffite charging up to Pilgrims Drop and Hawthorn Hill beyond.

Scheckter’s P34 caught the eye in 1976…

…but the screams of Laffite’s Ligier were irresistible

Ah, Laffite. At that time he had started just 15 GPs, of which he had been a classified finisher in only four, for F1 cars were seriously unreliable in those days, especially the ropey old Iso-Marlboros and Williams that he had theretofore managed to get his hands on. But he took the pole at Monza in 1976 with that caterwauling Ligier-Matra JS5, he scored his maiden GP win at Anderstorp in 1977 in its successor, the JS7, and he bagged podiums at Jarama and Hockenheim in the follow-up to the JS7, the JS9, in 1978. Then Ligier (temporarily) abandoned its oh-so-sonorous Matra V12 and opted instead for an “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” policy: the 1979 Ligier JS11 would be powered by a Cossie V8.

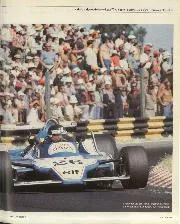

It turned out to be a brilliant car and, to my eyes, utterly beautiful, too. Laffite won its first race, in Buenos Aires, at a canter, having taken the pole with a lap more than a second ahead of that of his new team-mate, Patrick Depailler, who qualified second. For good measure Laffite drove fastest lap, also more than a second better than Depailler’s best. Two weeks later, in Sao Paulo, he made it two in a row, again taking the pole, this time ‘only’ 0.92sec ahead of Depailler in second, winning the race again and driving fastest lap again, this time ‘only’ 0.64sec better than Depailler.

At that point, unsurprisingly, Laffite was many pundits’ favourite for the 1979 world championship but, despite his early dominance, he never won a grand prix again that season and in the end he slumped to only fourth, beaten by not only the two Ferrari drivers, Jody Scheckter (first) and Gilles Villeneuve (second), but also by Williams’ Alan Jones (third). There were many reasons for Laffite’s comparative slump — he suffered eight DNFs in a 15-race season for example — but one of them was the irrational hauteur of the team’s eponymous founder, Guy Ligier, who took it upon himself to bully the JS11’s chief designer, Gerard Ducarouge, into giving it new sidepods that it did not need by the eccentric means of smashing them to smithereens and demanding that their replacements be made to a new design. The new ones made the car slower.

Laffite made a winning start to 1979 in Argentina with the JS11, but success would be short-lived

DPPI

Depailler leads at Jarama, ’79. Laffite missed a gear and retired as he chased down his team-mate

Laffite with Ducarouge on the Anderstorp podium as he celebrates maiden F1 win

Even so, if just a couple of bad breaks had instead gone Laffite’s way, he might still have held on to become 1979 world champion. He ended up on 36 points, 15 behind world champion Scheckter on 51, but had Ligier ordered Depailler to play second fiddle in order to support Laffite’s world championship bid instead of letting them race each other hell for leather, Laffite would not have over-revved his engine to a self-inflicted lap-16 retirement as a result of missing a gear when dicing flat-out with Depailler at Jarama. Depailler then won easily. Equally, two weeks later at Zolder, had he not again been battling Depailler in a dogfight which wore his Goodyears almost down to the canvas, he might have held on to win instead of dropping to second behind Scheckter. Do the math(s). The addition of those lost 12 points would have lifted Laffite’s total to 48, and the consequent subtraction of three points would have lowered Scheckter’s total also to 48. Neither of them scored points in the last grand prix of the year, Watkins Glen, but had the world championship been on a knife-edge, perhaps they might have. Anyway, it did not happen. But it could have and perhaps should have.

I did not meet Laffite until after he had returned to the F1 paddock as a commentator/pundit for the French TV channel TF1 in 1997. Had Twitter (or, if you insist, X) been around then, what soon became known among F1 fans in France as ‘Laffiteries’ would have quickly become globally notorious. I will give you just one example, but there are many. When Michael Schumacher attempted a professional foul on Jacques Villeneuve in Jerez in 1997, Laffite famously shouted “Quel con!”, which you do not need to be a scholar of French to translate. But he was indisciplined rather than cantankerous. At Monza in 1999 I interviewed him for a magazine feature that I was preparing to write about Depailler, which I had scheduled for the August 2000 edition, marking 20 years since his tragic, ghastly and unnecessary death at a Hockenheim test in August 1980. Jacques and I had been chatting away amiably for a quarter of an hour, despite my poor French and his only slightly better English, when Tim Schenken strolled by. “Tim, ici!” yelled my interlocutor. Schenken did as bidden, drew up a chair, and the two former Iso-Marlboro drivers began to chew the fat together about the good old days. My interview, it soon transpired, was over. But that was Jacques. He meant no harm by it.

From left to right Depailler, Guy Ligier and Laffite in 1979

DPPI

Laffite arrives at Montreal paddock for commentary duties in 2000

Getty Images

Indeed, he richly deserved his nickname — happy Jacques — and he remains universally popular to this day. I hope he is still happy, or at least content, but in 2018 he let it be known that he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease, and I gather that he is not very well at the moment. Nor, surprisingly, is he particularly well-off financially, despite his six grand prix victories and 32 grand prix podiums.

Today, November 21, 2023, is his 80th birthday. Happy birthday, happy Jacques.

Argentinian Grand Prix, Buenos Aires, 1979 I’ve always considered Argentina in 1979 to be my first real Grand Prix victory. I’d won in Sweden in 1977, but only because of…

Gerard Ducarouge, exhausted by months of off-season toil and the heat of an Argentinian afternoon, was only vaguely aware of the two Lotus engineers looking at his car as the…

Heard the one about Laffite at Dallas in 1984? In protest at the early hour of first practice, he turned up in his pyjamas. At Montreal one year, he arrived…

After three years of being the sole driver at Ligier, Laffite was suddenly faced with an equally fast Frenchman By Rob Widdows My God, I had so many! Which one…

Not many people have known Formula 1 from the inside better than John Hogan. For countless years he was ‘the man from Philip Morris’, the man responsible for Marlboro’s involvement…

How France eventually conquered Formula 1, one Swedish weekend The sport’s mother country has resumed her rightful place on the Formula 1 calendar. Though it’s a shame that the French…