“What that does is it really changes the attitude of the car and how you perceive its movement. And it makes it harder to predict compared to when you’re further back and sitting more centred. It is just something I have really struggled with.”

Back in the day Nelson Piquet used to complain to Gordon Murray about the same thing in the very long, very cockpit-forwards Brabham BT48. When the rear slid, he was late feeling it. It’s compounded in the case of the Mercedes because of its dynamics – ie what it’s actually doing rather than just what it feels like. As Hamilton describes it, its centre of aero pressure (the aerodynamic equivalent of the weight distribution) is moving forwards a lot as it is braked, giving a sensation of rear instability. But as he comes off the brakes and the car levels out, the centre of pressure is moving a long way rearwards – too far, making it difficult to get good rotation into the corner. So it has the worst of both worlds: rear instability under braking but a reluctance then to turn. So more steering lock is needed which, when the car finally grips up, pivots the car into oversteer mid-corner.

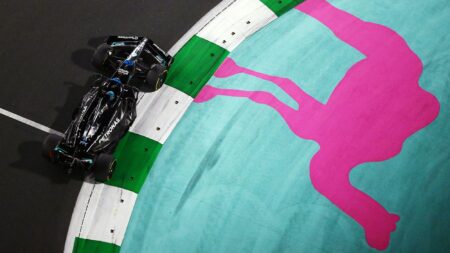

Moving centre of pressure gives Hamilton the worst of both worlds

DPPI

These traits make it extra important that the driver can accurately feel what the car is doing beneath him – yet that’s exactly what Hamilton isn’t getting because of the cockpit positioning. That’s the essence of his current problem with the car.

The generation of cars resulting from the ground effect regulations introduced last year all have a more rearwards centre of pressure. The throat of the venturi tunnels, where the underbody suction is at its peak, is somewhere just behind the driver’s bum. Previously, with the flat-bottom cars, the area of peak underfloor ground effect was at the leading edge of the floor, much further forwards. So when the car was braked, although the centre of pressure moved forwards, it didn’t do so by anything like the same amount as on these cars. It didn’t then move as far backwards when the car levelled out either.