Stuck’s wet weather skillset, reactions over feel, was largely irrelevant in the dry, but those qualifying tyres his wet track performance had earned him helped him put the Shadow an untypical eighth-fastest in the single dry session. He’d be starting between the megastars Lauda (Brabham) and Andretti. Stuck, who’d scored a meagre two points all season, would be starting ahead of the recently-crowned world champion.

Andretti had been at a loss to understand why his normally dominant Lotus 79 felt all at sea as soon he got out onto Saturday’s dry track. “The side bite through the turns is bad and it’s unstable under braking,” he reported. Later, it was found that in the rush to change from wet settings to dry, the camber was set incorrectly. With the car like that, he wasn’t able to generate the tyre temperature threshold at which the rubber began to work.

Tyres still behave like that today of course. In the post-qualifying analysis at Ferrari last weekend, in looking at why neither Charles Leclerc nor Carlos Sainz could make it out of Q2, it was noticed that over 50% of their pace deficit to the front came in Turns 1-2. Further analysis suggested the tyres were under-temperature at the start of the lap because they were under-pressured. From pole and a dominant victory in Monaco to mediocrity two weeks later.

Just as it was with Ferrari last weekend, so it was for Andretti 46 years ago. So even a Lotus 79 which habitually qualified 0.5sec or more clear of the field was effectively uncompetitive on this day at this track. That’s not a driver shortcoming. But if you look at the history books, you’ll see one Lotus – that of the stand-in driver Jean-Pierre Jarier – on pole, with Mario in the other 1.2sec slower in ninth. As ever, the circumstances need to be fully appreciated to give any perspective to that.

Hero to zero: Andretti and Lotus struggled at finale despite a season of dominance

Grand Prix Photo

That said, Jarier was performing magnificently. There really isn’t a current equivalent of his bizarre mixture of regularly electrifying pace but apparently casual indifference to putting the pieces in place in his environment. It was as if he had an incomplete picture of the constituent parts to success and the more his obvious talent went unrewarded, the more embittered and non-caring he became. But in the tragic circumstances of Ronnie Peterson’s death at Monza, Jarier – who had been out of a drive since being dropped by ATS mid-season – suddenly found himself in a car worthy of his talent. Which put him in place to remind the F1 world of just what he could do. It seemed a long time since he’d been on pole for the first two races of ’75 and cruelly robbed of a dominant win in Brazil by a mechanical failure. He was about to get that rarest of things in F1: a second chance. Here he sat on pole ahead of Jody Scheckter’s Wolf, John Watson’s Brabham, Villeneuve, Fittipaldi and the Williams of Alan Jones.

Aside from Stuck, there were a few other stand-out performances on that wet Friday track. Didier Pironi, completing his rookie F1 season in an otherwise mid-grid Tyrrell, was just behind Stuck in the opening session, the second-fastest Goodyear runner. Pironi was ahead of another rookie, the spectacular Keke Rosberg, who had the car of the tiny ATS team at all angles in full attack mode. That year’s British F3 champion Nelson Piquet – who’d done a couple of grands prix with little teams earlier in the season – was making his first appearance for Brabham, in a third car alongside Lauda and Watson.

Unencumbered by any previous experience of the car and not knowing that it wasn’t handling as well as usual, he was seventh-quickest in the opening session, with Watson 18th and Lauda 24th. Team boss Bernie Ecclestone suggested to his two superstars that perhaps it was time they gave thought to retiring. Watson was already on his way out of there for ’79, to replace McLaren’s original signing Peterson. Piquet would be Watson’s replacement – and the foundation of his two world championships with Brabham were put in place on that cold, wet Montreal session.

Nelson Piquet in his Ensign-Ford earlier in 1978 at Hockenheim

Grand Prix Photo

Without the qualifying tyres of his senior team mates (worth around 1sec), in the dry Piquet was well behind them on the grid. Similarly, neither Pironi nor Rosberg could repeat their wet track form. Rosberg found himself without rear brakes as soon as he took to the track but realising there may not have been time to fix that just stayed out there in the ATS, attacking like crazy in between wild spins. He scraped onto the back row of the 22-car grid, faster than the six non-qualifiers. It was the sort of rough-hewn improvisation and commitment which would come to win him races in the future and the world title of ’82. How good was the performance which put him on the back row of the grid that day? Those on the team who understood the circumstances would probably have judged it to be comparable with the best. But the onlooking world would barely have registered it.

Rosberg would be without a drive going into ‘79 but would be picked up by Wolf mid-season after James Hunt decided suddenly to retire. Here, in his last race for McLaren, Hunt was nowhere, 20th on the grid and out-qualified for the one and only time by team mate Patrick Tambay. But again, it was circumstantial. With his race chassis misbehaving at the start of practice, he swopped to the T-car, which then had its throttle linkage fall apart before he’d done a representative lap.

Neither Hunt (left) or Tambay (right) had a particularly memorable Canadian GP

Grand Photo

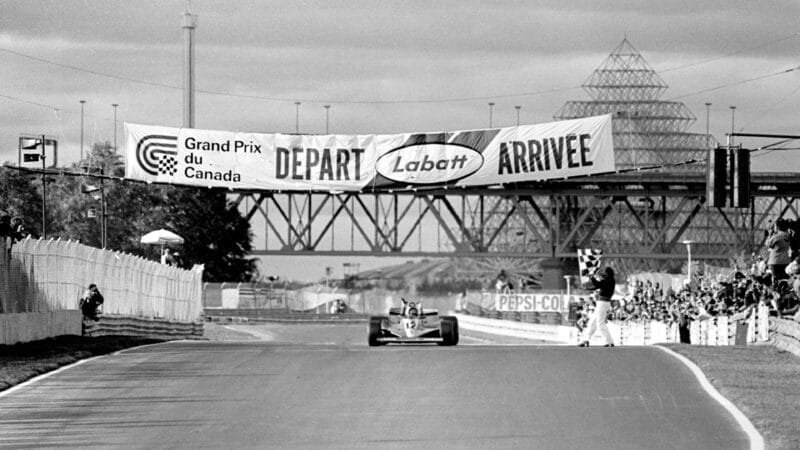

The fairytale of Gilles Villeneuve’s famous first victory unfolding on his home track came at the expense of Jarier. He’d led from the start, was well clear of Stuck taking out himself and Fittipaldi at the first corner, and by half-distance he’d had the Lotus half-a-minute clear of the field. A holed oil radiator brought him into the pits after 49 of the 70 laps.