How real are Red Bull's concerns that Verstappen could leave early?

Helmut Marko caused a stir after the Bahrain GP with his worries that Max Verstappen could leave Red Bull early. But how real are those fears?

Technical regulations come and go. But will the latest changes in 2026 shake up the running order?

Grand Prix Photo

The biggest technical regulation changes in recent memory are set to hit the F1 grid in 2026, with widespread changes to the hybrid power unit and aero systems set to change not only the way the cars look and how they race but also the competitive order.

Although not all on the same scale, technical rule changes have been a part of F1 for over 70 years. But in the modern era, game-changing overhauls to the rulebook have generally been made for three main reasons: to increase driver safety, to reduce a single constructor’s runaway advantage or to create a more level playing field.

The latest changes are based mostly around the latter two points, as Red Bull‘s dominance in the current ground-effect era of racing has often made race weekends tedious and predictable. In 2026, the running order could face a massive shake up, with the series switching to new V6 hybrid power units which will run on fully sustainable fuels and produce three times the electrical power.

These engines will also be considerably cheaper to manufacture, due to the banning of expensive materials and systems such as the MGU-H, which has encouraged the likes of Audi to join the series with a good chance of being a competitive outfit almost immediately. Active aerodynamics is also likely be play a key role and the cars themselves will be slightly narrower, shorter and 30kg lighter.

Only time will tell if the new set of regulations will have their intended effect on the field and F1 as a whole. But perhaps a timeline of the series’ biggest regulation changes that have gone before, could give us a hint as to what 2026 might hold in store. We’ve compiled them below.

Red Bull has dominated under the new ground effect regulations

Red Bull

The 2022 technical regulations created a completely new generation of F1 cars, with performance focused primarily around aerodynamics — more specifically, ground effect.

First introduced by Lotus in 1977 and later made infamous by the all-conquering Lotus 79 which dominated the 1978 F1 title race, ground effect aerodynamics generate huge amounts of downforce by creating an area of low pressure underneath the car with a low-riding, contoured floor. This, coupled with a redesigned front and rear wing, aimed to stick a car to the road without generating as much turbulent air behind it, theoretically allowing drivers to race closer for longer.

The introduction of 18-inch tyres also aimed to improve handling and winglets above the front tyres were designed to direct dirty air flow away from the rear wing.

In addition to the aerodynamic changes, there was a freeze on power unit development — limiting the resources teams could use to upgrade engine components — as well as an increased minimum car weight of 798kg (making the new cars 46kg heavier than the previous generation). The budget cap, introduced the previous season, was lowered from $145m to $140m per constructor.

Red Bull’s Adrian Newey-designed cars have dominated most of the current era, but faces stronger competition in 2024.

Wider cars made for much quicker lap times

Grand Prix Photo

Then-F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone aimed to make F1 look more exciting in 2017 by introducing regulations which made cars wider, cutting lap times by 4-5sec.

The width of the chassis was increased by 20cm, the front and rear tyres were widened by 6cm and 8cm respectively and the rear wing was made 20cm longer and brought 15cm lower. This made for a sleeker profile which increased downforce and allowed drivers to carry more speed through corners. The size of the rear diffuser was also increased.

Although the dominance of Mercedes persisted due to the power it could generate from its hybrid power unit, the new regulations did reduce its margin of advantage. After scoring 19 race wins in 2016, the Brackley outfit only managed 12 in 2017 — although it still secured a fourth consecutive constructors’ title and a drivers’ title with Lewis Hamilton.

Powered by a new hybrid engine, Mercedes were quicker than anyone else in 2014

Grand Prix Photo

New regulations in 2014 saw the introduction of the 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrid engine which replaced the 2.4-litre naturally aspirated V8s that had been used in F1 since 2006.

The new power unit not only burned through 50kg less fuel per race, but also featured an uprated Energy Recovery System (ERS) which produced 150kw of power that could be deployed for up to 30 seconds per lap. The look of the car also changed, with the introduction of a narrower front wing, larger sidepods and a reduction of the rear wing.

Mercedes, which had returned to F1 in 2010 after a 55 year hiatus, was the main beneficiary of the change, thanks to its power unit, which was superior in terms of power and efficiency. A seven-year period of domination began, in which Mercedes claimed every championship on offer.

Jenson Button and Brawn GP were the kings of the new aero era in 2009

Grand Prix Photo

The wide sweeping technical rules changes of 2009 are remembered for one of the biggest single-season shake ups of the running order in F1 history.

With the intent of enabling drivers to follow more closely and increase overtaking opportunities, F1 placed a ban on a wide range of aerodynamic devices including winglets and flip-ups and replaced them with a new high and narrow rear wing as well as a lower and wider front wing — which could be adjusted twice per lap.

Grooved tyres were replaced by slicks and a Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS) was introduced, which allowed drivers to utilise a 82bhp power boost for 6.6 seconds per lap.

Engines were not allowed to exceed 18,000rpm and rear diffusers were limited in their size and shape.

As a result of the changes, a fairytale story emerged from the ashes of the Honda team — Brawn GP won both the drivers’ and constructors’ championships at the first time of asking, partly thanks to its innovative double diffuser.

Thinner cars made for marginally better racing

Clive Mason/Allsport via Getty

Much as in 2017 and 2022, the look of F1 cars changed drastically in 1998 as they were made 20cm narrower and grooved tyres were introduced. These changes were made in an effort to slow them down by reducing grip levels — in the name of safety.

“The simplest way to reduce grip was to reduce the size of the tyre contact patch, and the easiest way to do that would be narrower tyres,” said FIA president Max Mosley. “But if we decreased the maximum tyre width, the straight line speeds would increase because a very high proportion of the aerodynamic drag of a F1 car comes from the wheels and tyres.

“So for a smaller contact patch, we needed some form of tread.”

The results of the changes made the cars slower by an average of eight-tenths per lap at most circuits.

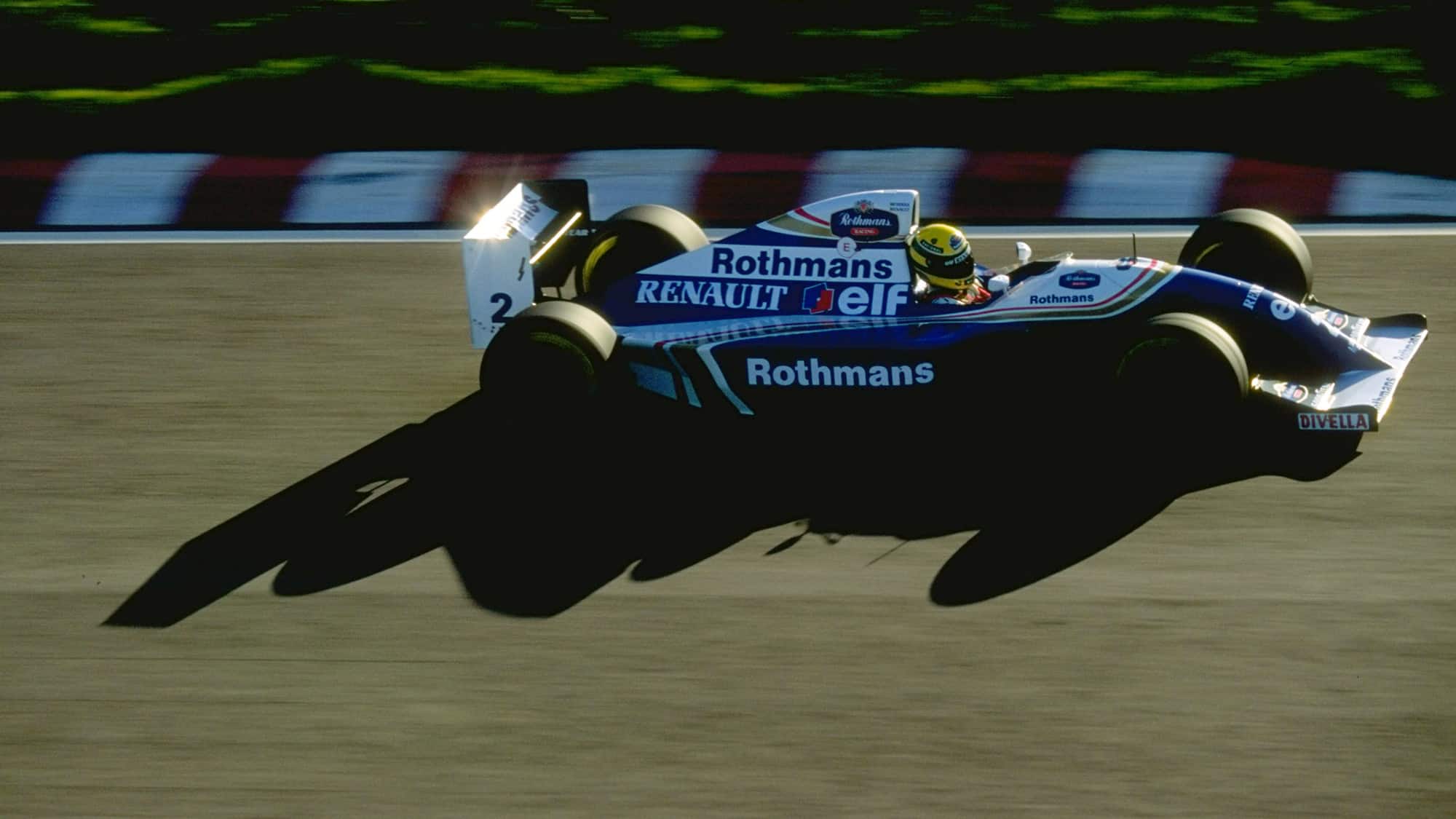

The elimination of driver aids made some cars extremely difficult to drive and equally dangerous

Mike Hewitt/Allsport via Getty Images

In the early 1990s driver aids became increasingly common on F1 cars, with Alain Prost‘s title-winning Williams FW14C of 1993 — which featured active suspension, traction control and an ABS braking system — often cited as the most technologically advanced car of the era.

In 1994, all such devices were banned in a bid to put more control in the hands of the drivers, although there were some suspicions — vehemently denied to this day — that Benetton had a secret traction control system that was aiding Michael Schumacher‘s title run.

Mid-race refuelling was also reintroduced after it had been banned in 1983, allowing the cars to become lighter due the reduction in fuel loads and tank size.

The lack of a turbo did little to curb McLaren’s dominance

Grand Prix Photo

Turbocharged engines were banned entirely in 1989 on the basis that they were too powerful, too dangerous, and too expensive. In its place, teams were instructed to use 3.5-litre naturally-aspirated engines, which soon prompted the use of airboxes above the driver’s head in order to properly cool the machinery behind them.

McLaren’s Honda engine proved to be the class of the field, and allowed the Woking outfit to continue the dominance it had enjoyed in the years before. Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost scored 10 race victories between them, the latter was crowned world champion and McLaren took a second consecutive constructors’ championship.

Flat bottom cars turned the F1 world on its head in 1983

Grand Prix Photo

Following the success of the all-conquering Lotus 79 in 1978 which drove Mario Andretti to a dominant world title, ground effect aerodynamics spread through the F1 paddock like wildfire with each team adopting its own iteration.

But amid concerns of increasing cornering speeds — with some cars ‘bottoming out’ and losing all grip mid-corner — the decision was made to ban ground effect aero entirely in 1983. In its place, teams were ordered to run flat-bottom cars which dramatically decreased the amount of downforce that could be produced. Side skirts were also outlawed, making it impossible to seal in any air that would otherwise be trapped under the floor.

Helmut Marko caused a stir after the Bahrain GP with his worries that Max Verstappen could leave Red Bull early. But how real are those fears?

Ayrton Senna’s tragic final races in 1994, marked by controversy over illegal traction control and his relentless pursuit of excellence in a challenging car, remain a poignant chapter in F1 history, as Matt Bishop recalls

Full F1 schedule for the year, including the next F1 race of 2025: the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, the whole calendar and circuit guides for the 24-race Formula 1 season

Round five of the 2025 Formula 1 season wraps up the first triple-header of the year in Saudi Arabia. There are the dates and start time for the Jeddah event, including all sessions