On race day Jabouille led easily for the first 61 laps, until a puncture ended his run: was there ever a grand prix driver bar Chris Amon so luckless? Arnoux then took over and won by more than half a minute. Second and third were Laffite and Pironi, making the podium an all-French celebration. Piquet and Reutemann were fourth and fifth, albeit a long way behind, lapped in the case of the Williams man.

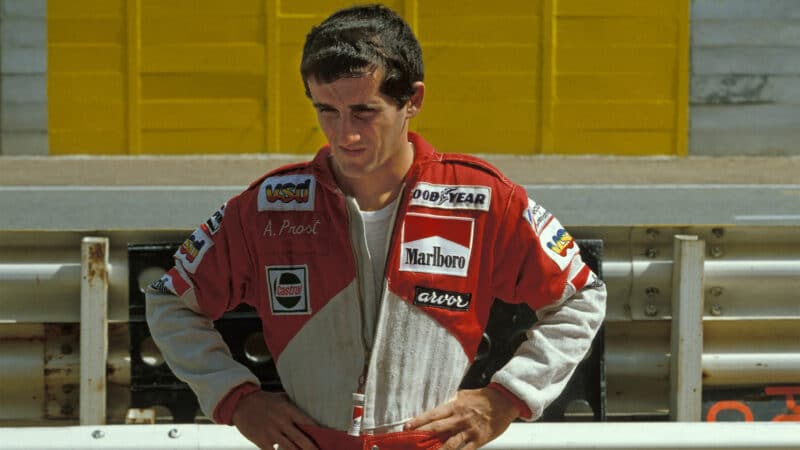

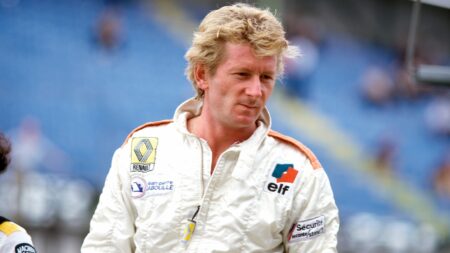

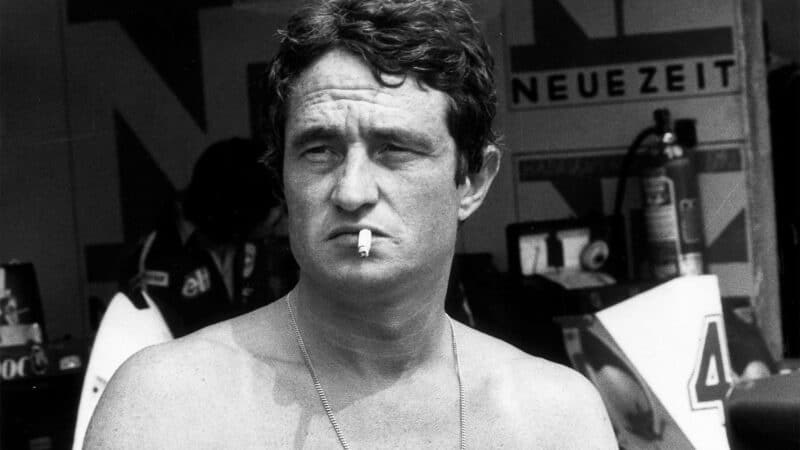

I have mentioned four French drivers so far — Jabouille, Arnoux, Laffite and Pironi. But, among the 26 men who qualified for the 1980 South African Grand Prix — yes, 26, please take note, Mario Andretti, Michael Andretti and indeed Stefano Domenicali — there were three more, all exceptional in their way, all of disparate character, all at differing stages of their F1 careers: Jean-Pierre Jarier, Alain Prost and Patrick Depailler. That was how F1 was back then, for, thanks in large part to Francois Guiter, the visionary marketing director of the French oil company Elf (Essence Lubricants France), vast sums of petro-francs were poured into financing the coaching of quick French boys at the Winfield School based at the Magny-Cours circuit. It worked. Now France has only Pierre Gasly and Esteban Ocon in F1, and as recently as 2011 it had no F1 drivers at all. Guess how many French drivers raced in F1 in the 1970s and 1980s. The answer, dear reader, is 29.

Gifted but indisciplined, Jarier had looked as though he was going to drift out of F1 after being fired halfway through 1978 by Günter Schmid of ATS, whose car he had failed to qualify at Monaco. Then, four months later, Ronnie Peterson died of injuries sustained at Monza, and Jarier inherited his Lotus drive for the last two grands prix of the year. At Watkins Glen he qualified eighth, well behind team-mate Andretti, who had taken the pole by a mile, but in the race ‘Jumper’ was a sensation, carving his way through the field to third before he ran out of fuel four laps from the end. He had shown all his old flair, and no-one else had got within 1.5sec of his astonishingly rapid fastest lap. The following weekend, in Montreal, he took the pole and led the first 49 laps, with ease, until he was robbed of victory by a leaking oil cooler. But he had made his point. He was duly signed by Tyrrell for 1979, he bagged two podiums for Uncle Ken that season, and by Kyalami 1980, still racing for Tyrrell, he and his career appeared to be well and truly back on track.