The first-year report on the cost cap was finally published in October 2022. Most teams were found to have complied, but Williams was picked up for “procedural” breaches – to do with financial reporting – and Red Bull was found to have overspent.

Red Bull was fined $7m (£6.05m) and had its aerodynamic testing allowance cut by 10% for a year as a result of spending £1.864m (1.6%) above the cap, which was classified as a minor breach (of less than 5%).

Not all rivals were content. Lewis Hamilton pointed out that even a small overspend could have a significant effect – particularly in the close 2021 season where Max Verstappen controversially beat him after the final race in Abu Dhabi. Hamilton claimed that he could have won the 2021 title if Mercedes had spent an additional $300,000 (£270,000).

The cost cap was one of three key measures introduced to make F1 more equal and deliver closer, more unpredictable racing. Along with the spending limit came more stable funding, as a new commercial rights agreement shared F1 revenue more evenly between teams. The new 2022 technical regulations then introduced ground effect to allow cars to follow – and fight – more closely.

Scroll down for an in-depth look at the cost cap and how it works.

What is the cost cap?

The cost cap limits how much each F1 team can spend in a single season in a bid to level the playing field across the grid and make the sport more financially sustainable.

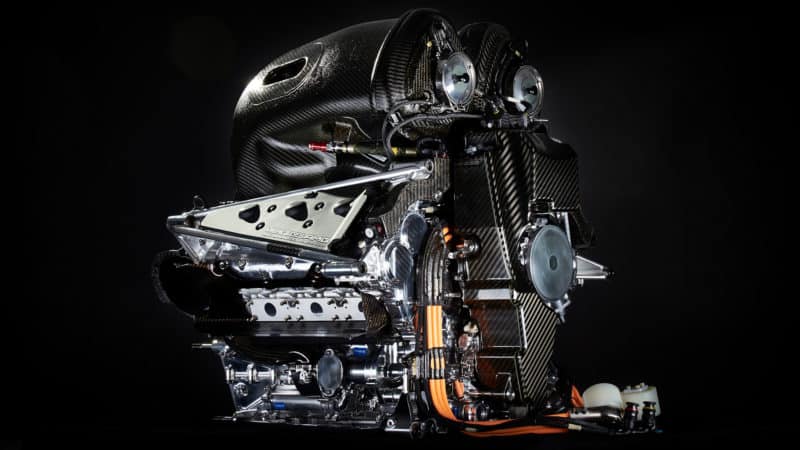

It applies to most salaries, car development costs and race weekends, including transport, but does not apply to the cost of buying in an engine, for customer teams, or developing a power unit for factory teams (this is subject to separate cost restrictions).

Engine costs are excluded from the budget cap

Mercedes

After years of different proposals, the $145m cost cap first came into force for the 2021 season, as teams were working on the following year’s new-generation car. The spending ceiling will reduce by $5m a year for the following two seasons. Development costs should be lower as technical rules remain almost unchanged, and the lowering cap is expected to push teams to greater efficiencies.

How much is the cost cap?

When Formula 1 first introduced its cost cap in 2021, the maximum annual budget was set at $145 million (£108m) per team, aimed at reducing the spending disparity between the grid’s frontrunners and backmarkers.

This figure has gradually decreased over subsequent seasons, but inflationary adjustments have since become a regular part of its annual application.

Here’s how the cap has evolved:

2021: $145 million

2022: $140 million (with a 3.1% inflation adjustment mid-season)

2023 onward: $135 million baseline, adjusted annually for inflation

As of 2025, the base figure remains $141.2 million (£106m), but adjusted for inflation, the effective cap for this year is approximately. The final number is confirmed before each season begins by the FIA’s Cost Cap Administration.

Teams are also granted additional allowances based on calendar length. For every race beyond 21 rounds, the cost cap increases by $1.8 million per additional Grand Prix.

A major change is expected in 2026, with the cost cap set to rise to around $215 million (£160–165m), pending FIA ratification. This figure is linked to the introduction of new technical and power unit rules, which will also bring previously exempt categories — such as capital investments and HR costs — under stricter control.

Questions over the cost cap

After the intense scrutiny surrounding Red Bull’s breach in 2021, the FIA welcomed a much-needed period of relative calm.

For both the 2022 and 2023 financial reviews, the FIA’s Cost Cap Administration found that all 10 Formula 1 teams were fully compliant with the cost cap regulations. This move has helped reinforce the credibility of financial governance in the sport.

However, the atmosphere off track remains far from settled. Persistent doubts linger about whether factory-backed teams with other ventures – such as road car divisions – could use innovations or R&D from outside their F1 operation to gain an edge without charging these advances to their capped F1 budgets.

Red Bull accepted development restrictions after cost cap breach — not that they appear to have held it back

Chris Putnam/Future Publishing via Getty Images

In response to ongoing concerns, the FIA issued a new technical directive requiring teams to include in their declared budget the cost of any intellectual property (IP) transferred into Formula 1 from external, non-F1 projects or arms of their wider companies.

This move, widely regarded as “closing a loophole,” is designed to ensure that advances developed in non-F1 divisions – such as hypercar projects or commercial engineering subsidiaries – cannot be imported into F1 cars without full financial transparency.

Despite robust regulation and auditing, suspicion remains among the teams. Some in the paddock question the frequency and sophistication of updates being introduced by rivals – especially factory squads with considerable resources. There is concern that rapid in-season development and major investments in factories or infrastructure might still elude the full net of the cap, even with new IP rules.

As Formula 1 looks ahead to a major regulatory overhaul in 2026, the debate over effective financial policing – and the balance between competitive innovation and fair play – remains a live topic in the championship.

What does the cost cap cover?

The cost cap covers most performance-related spending, including:

- Car design and development

- Components and manufacturing

- Race operations

- Wind tunnel and CFD operations

- Team personnel involved in performance

The most crucial area of these cost cap rules is car development: teams must now make crunch decisions on which parts to develop, how much to spend on these parts and how many they need – all the while keeping it under the budget cap.

The cost of repairing accident damage or replacing failed parts all comes out of the budget cap, so a few unfortunate races can make a significant dent to upgrade plans.

Promotional activity, such as this zero-gravity pitstop, doesn’t count towards the cost cap

Red Bull

What does the cost cap not cover?

A number of standout costs are not included in the budget cap, which are:

- Driver salaries

- Salaries of the top three team executives

- Marketing and hospitality

- Property and capital expenditure

- Power unit development (covered under a separate cap – see below)

Special provisions have been approved for new entrants such as Audi and Red Bull Powertrains, covering the 2026–2028 period to account for set-up-phase expenses and local labor cost differentials.

Audi, operating under the Sauber-Audi F1 Team name, is already being pre-audited under 2025’s financial procedures.

What is the penalty for breaking the cost cap?

Penalties have not been clearly set out, partly to avoid a situation where teams see the benefits of breaching the cost cap outweighing the penalty that they would face.

Another factor is that points deduction penalties only apply to the season in which the breach occurred, resulting in a season where championships could be changed almost a year after they seemed to be decided.

If a team makes an overspend of under 5%, then that is classed as ‘minor’ breach and can be penalised with fines, points deductions or development restrictions. Anything more and it is a ‘major’ breach, which is likely to attract more severe penalties and could result in a team being thrown out of the championship.

The potential penalties could be one or more of the following:

| Penalties for minor breaches | Penalties for major breaches |

| • A fine, calculated on a case-by-case basis • A public reprimand • Deduction of constructors’ championship points for the year of the breach • Deduction of drivers’ championship points for the year of the breach • Suspension from one or more stages of a race weekend (not including the race) • Restrictions on aerodynamic or other testing • Reduction of the cost cap |

• Deduction of constructors’ championship points for the year of the breach • Deduction of drivers’ championship points for the year of the breach • Suspension from one or more stages of a race weekend (not including the race) • Restrictions on aerodynamic or other testing • Reduction of the cost cap • Exclusion from the championship |

Who decides the cost cap penalties?

It was originally stated that any break of the cost cap would have penalties decided by the Cost Cap Adjudication Panel, where the full range of penalties could be applied.

However, with the recent Red Bull cost cap breach, the FIA prevented things reaching that stage by offering an ‘Accepted Breach Agreement’, essentially a negotiation process which exists in the financial regulations.