Yet from another perspective, it’s also an entirely logical move. In terms of what Alpine requires right now, in the midst of its increasingly desperate spiral into sad backmarker status, Briatore is precisely what it needs. And in F1, practical needs-must demands always overrule anything that prickles the conscience. That’s how it’s always been.

So why is Briatore just what Alpine needs? First, I should add the caveat that he’s not ‘THE ANSWER’. Clearly, he doesn’t have the power, knowledge or understanding to single-handedly lead the blues triumphantly up the grid and win back all of its damaged pride. Of course he’s not that person. He’s not Adrian Newey… In fact, Briatore has revelled in his technical ignorance of F1, from the moment he parachuted (against his own better judgement) into what was then Benetton at the start of the 1989 season.

But while Briatore knows precious little about F1 technically, he knows everything about how it operates. He is the ultimate hustler, always on the make for a deal, but who does so having looked and listened closely to make sure he lands the right one. I’d argue there’s been no one better and more effective in F1, ever.

That conclusion became clear when I was researching my book Benetton: Rebels of Formula 1. As Symonds and others told me, Briatore was considered warily by the engineering team when he first pitched up at the team’s Witney base. Even more so when Symonds overheard him dismiss employees as “ just engineers” at his first grand prix with the team in Rio at the first race of 1989.

But thereafter all of them made it clear that, for all of his obvious ignorance, Briatore did prove to be a highly effective and actually often decent boss and leader. “I’m not sure I’m going to get on with this guy,” Symonds told me on his first impression. “In actual fact I did get on with him very well and he has a lot of admirable qualities. There were some big changes in Flavio over the years.”

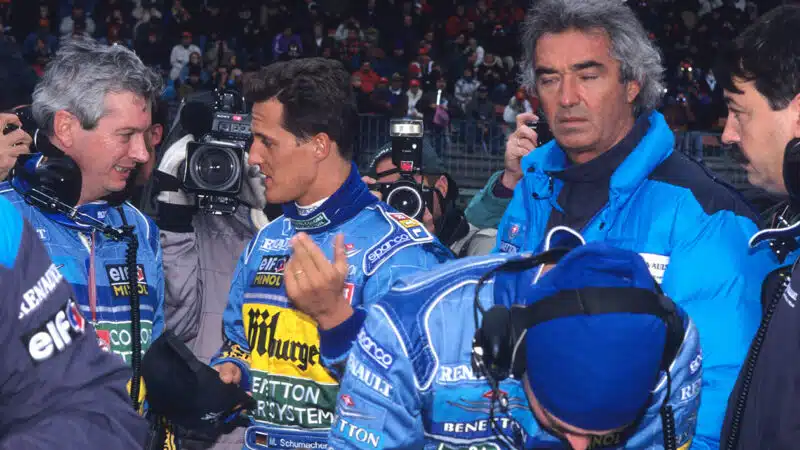

Briatore with Nelson Piquet in 1989, his first season as Benetton boss

DPPI

There are plenty of funny stories. How he created his own apartment within the Enstone base to stay overnight, complete with fake book cases and framed photos of him kissing all sorts of celebrities; how engineers late one night ran up an engine, then heard applause when they switched it off, only to encounter Flav in his velvet dressing gown and ‘Ali Baba’ slippers; comical exchanges on the pitwall, when often his colleagues had no hope of deciphering what he said, given the strength of his slurring accent; and his admittance that even if they had understood him, his words probably wouldn’t have made much sense!

Yet at the same time, none of them underestimated Briatore – and all I spoke to recognised what he brought to the team, as a leader who wasn’t afraid to make the big calls. He listened, learned and understood in whom he should place his trust when it came to running each department. Even if he didn’t necessarily know or at least remember all their names… As for the reversed baseball caps and music turned up to 11 in the garage, what a great way to further get under the opposition’s skin. Life was fun under Briatore and he inspired a certain confidence that all winners need.

Sure, he made mistakes. Hiring both Gerhard Berger and Jean Alesi from Ferrari in apparent vengeance for Michael Schumacher’s defection in 1996 wasn’t his finest moment, especially as their salaries took up vital budget that could have been better spent elsewhere. But overall he made more good calls than bad ones.