F1 tales of the unexpected: the best of Matt Bishop from 2024

Each Tuesday in 2024, Matt Bishop has brought his idiosyncratic, deeply researched and often first-hand tales to Motor Sport readers. Here are five of the best

He’s an encyclopedia of racing history; a former F1 insider with notebooks full of juicy conversations; a previous magazine editor with a vast vocabulary; and an eye for a fascinatingly obscure anniversary.

Over the past year, Matt Bishop has brought his vast experience to the pages of Motor Sport, the subject matter only marginally less predictable than the gripping diversions and statistical anomalies as his column winds from start to finish.

We’ve learned that Lewis Hamilton has been planning to drive for Ferrari for many years; of how Sebastian Vettel decided to retire; of Christian Horner’s early ambition; as well as of dozens of figures from racing’s past, brought to renewed life. All unbroken by Matt’s month-long stint in hospital, during which he (of course) coined a new mantra for living.

As we look forward to another year of unexpected Tuesday morning columns, Matt has chosen five of his favourites from 2024 to savour once more.

‘Lewis, listen, delete that Tweet!’ – when Hamilton posted secret McLaren data

Lewis Hamilton was still developing into an assured F1 champion when, in 2012, he revealed confidential McLaren telemetry after a disappointing Belgian GP qualifying session. Matt Bishop was the first to confront him

September 3, 2024

Hamilton took Spa setbacks to heart in 2012

Mark Thompson/Getty Images

Motor sport purist that I am, I reckon late summer should be Belgian Grand Prix time, or Italian Grand Prix time, or both. Well, we have just enjoyed watching Charles Leclerc win the 2024 Italian Grand Prix, on September 1, which timing is spot-on in my view, but this year’s Belgian Grand Prix was won by Lewis Hamilton some weeks ago, on July 28 to be precise, which is about a month early to my mind. Indeed, if you are reading this column on the day on which it was published – September 3 – then you are doing so almost exactly 12 years after Hamilton’s then McLaren team-mate Jenson Button won the Belgian Grand Prix in its traditional late-summer time slot, September 2, 2012, on which fine Sunday he reeled off the 44 laps to complete as serene a domination of a Formula 1 race as you are ever likely to see.

I was McLaren’s comms/PR chief at the time, I was in my fifth year with Lewis and my third with Jenson, I worked differently but closely with each of them, and I had grown not only to like but also to admire them both. When we rocked up at Spa for the 2012 Belgian Grand Prix, Lewis had won one F1 world championship and 19 F1 grands prix, and was 27 years old. Jenson had also won one F1 world championship, and 13 F1 grands prix, but at 32 he was that bit older than Lewis, and he was possessed of a degree of emotional poise that the younger man was then lacking; to be clear, Hamilton has it in abundance now, a dozen years later.

What do I mean by ‘emotional poise’ in that context? Let me put it this way. Although they were both very successful sportsmen — famous, popular, and rich beyond any normal needs — they treated triumph and disaster very differently. All sports stars, even illustrious ones like them, encounter every bit as much disaster (or defeat) as triumph (or victory). During the time that I was working with them, Button was able to take such disappointments on the chin; Hamilton was not.

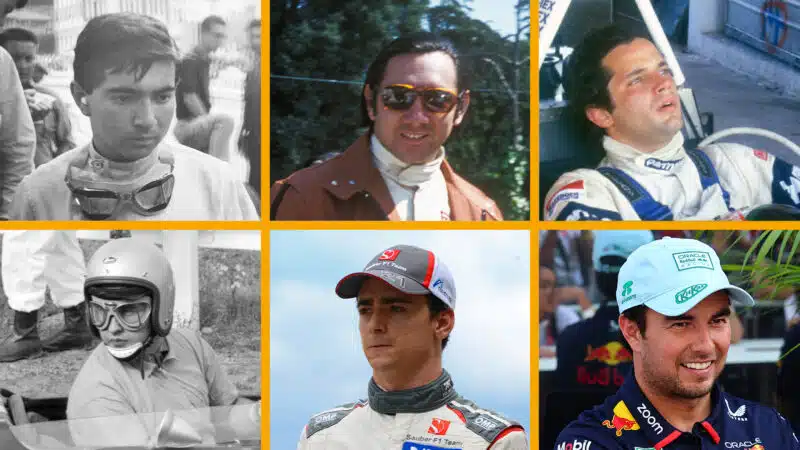

Mexico’s six F1 drivers: tragic heroes, recent talents and a pay driver pioneer

Only six Mexican drivers have ever raced in Formula 1 — but each has left their mark on the world championship. Matt Bishop looks back on their careers

October 29

Mexico’s F1 history: From the triumph and tragedy of the Rodriguez brothers, to the shortcomings of Sergio Perez

Younger readers may possibly regard the Mexican Grand Prix as a new-ish thing, since, prior to its recommencement in 2015, it had not been a part of the Formula 1 world championship for a generation. But last Sunday’s race, won faultlessly for Ferrari by Carlos Sainz, was the 24th world championship-status F1 Mexican Grand Prix, and, apart from a flurry of five (1988-1992) that were run in early summer, all of them have taken place at this time of year.

There have been six Mexican F1 drivers, and none of them has won his home F1 race. Two local lads contested the first world championship-status F1 Mexican Grand Prix, in 1963: Pedro Rodriguez and Moises Solana, and their racing careers were very different. I will explain why that was in a little while, but, before I do so, I should tell you about the 1962 Mexican Grand Prix, which was a non-championship F1 race that was principally supported by British F1 teams, eager to learn about a new high-altitude circuit that would become a part of the F1 world championship the following season.

So it was that no fewer than 13 Lotuses were entered, plus three Coopers, a Brabham, a Lola, oh and three Porsches. One of the Lotuses, the one run by that great privateer Rob Walker, whose cars Stirling Moss had already raced to eight F1 grand prix victories between 1958 and 1961, was to be driven by Ricardo Rodriguez, Pedro’s little brother, who was just 20. Talented and precocious, at Monza the year before, 1961, Rodriguez Jr had become the youngest driver to race for Ferrari — a record that Oliver Bearman finally beat at Jeddah seven months ago.

The lonely death of B Bira, Thai racing prince, adventurer and Olympian

Thai royal Prince ‘B Bira’ was an accomplished racer, an aviator, an Olympian and gifted artist. And yet, after a life of adventure, he died anonymously at a London Tube station

July 16

Bira toasts victory in the JCC International Trophy race at Brooklands in 1936

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In the 75-season (1950-2024) history of the Formula 1 world championship there have so far been just two Thai drivers. One of them is current Williams ace Alex Albon, who was born in London’s Portland Hospital in March 1996 to a Thai mother, Kankamol Albon, who was sent to prison for fraud in 2012; his father Nigel Albon is British and indeed raced in the British Touring Car Championship in 1994.

And the other Thai F1 driver? Step forward His Serene Highness Prince Birabongse Bhanudej Bhanubandh of Siam (the official name of Thailand until 1939), which mouthful he abbreviated during his racing career to B Bira, who was born in Bangkok’s enormous and labyrinthine Grand Palace in July 1914, almost exactly 110 years ago, to Mom Lek Bhanubandh na Ayudha; his father was His Royal Highness Prince Bhanurangsi Savangwongse Vongsevoradej. Like Albon, he was educated at public school in England, Eton in Bira’s case.

Albon has not (yet) won an F1 grand prix, but he has stood on two F1 grand prix podiums, at Mugello and Sakhir in 2020, the second of his two seasons as a Red Bull driver. Bira won a number of significant races in the 1930s, earning the much coveted BRDC Road Racing Gold Star in 1936, 1937, and 1938, but he never won a world championship-status F1 grand prix, although he scored two podium finishes in non-championship F1 grandes épreuves, at Reims and Monza in 1949, and two wins in lesser non-championship F1 races, at Goodwood in 1951 and at Chimay in 1954. His final victory of any note came at Ardmore, New Zealand, in 1955, where and when he beat a decidedly mixed field, advantaged as he was by his state-of-the-art Maserati 250F F1 car, ranged against great drivers in decent cars (eg, Jack Brabham in a Cooper T23 ‘Redex Special’), good drivers in average cars (eg, Ross Jensen in a heavily modded Triumph TR2), and indeed veteran eccentrics in old and oddball cars (eg, George Smith in a 1939 Alfa Romeo Bimotore ‘Gee Cee Ess’ powered by a 5.6-litre Chrysler Fireball Hemi V8). If you are interested in a further arcane detail, you may like to know that Smith was a big man – OK, fat – who made a habit of eating apples during races and hurling the cores at flag marshals as he sped past them.

The Alex Wurz you don’t know: F1 driver of many talents is ideal for top job

Alex Wurz’s racing CV includes F1 podium finishes, two Le Mans victories and extensive testing mileage. But, says Matt Bishop, few know how accomplished he’s been out of the cockpit

February 13

Alex Wurz: F1 driver, Le Mans winner, BMX champion. And that’s just the start

Eric Alonso/F1 via Getty images

You think you know Alex Wurz? Think again. Yes, he raced in 69 Formula 1 grands prix between 1997 and 2007, for Benetton, McLaren and Williams, bagging three podium finishes but no wins, and he tackled the Le Mans 24 Hours nine times between 1996 and 2015, in Porsches, Peugeots and Toyotas, winning it outright twice. In 1996 he became the youngest ever outright winner, at 22, which record he still holds 28 years later; and in 2009 he won it again. But you know all that.

You may also know that he won races in Formula Ford, Formula 3, FIA GTs, Le Mans Series, American Le Mans Series, International Le Mans Cup, and WEC; and that, as a full-time test driver for McLaren between 2001 and 2005, and for Williams in 2006, in the days when F1 teams used to field separate test squads that ran long and frequent programmes at Barcelona, Jerez and Valencia, he drove more testing miles than anyone except Ferrari’s extremely long-serving warhorse, Luca Badoer. You may even know that he won the BMX world championship in 1986, aged 12. But all that is in his past. So, what about his present? Well, he is extremely busy, and he is girding himself for a big milestone: on February 15 he will turn 50.

His future, from a professional point of view, like that of all of us, depends on how he can deploy his experience and expertise to suit best his options and opportunities. His experience and expertise as a racing driver constitute a gilt-edged curriculum vitae – obviously. But there are quite a few other ex-drivers of his approximate vintage whose CVs are not dissimilar. However, Alex has many more strings to his bow than merely racing experience and expertise.

Max Mosley: ‘As much sinner as saint, but we’ll never see his like again’

Max Mosley shaped F1 — and modern motor sport — as we know it, doing good and bad. Matt Bishop examines the complex character of the former FIA president

April 9

A toweringly intelligent and often charming man, yet disturbingly complex and sometimes cruel, Max Mosley died by his own hand on May 23, 2021, aged 81, having informed his personal assistant Henry Alexander that he was going to end his life, the reason being that his doctors had told him that his cancer had become terminal and that he had only weeks to live. The way he dispatched himself was typically resolute. He had dinner with his wife Jean, whom he had married 61 years before, during which repast he ate and spoke less than he usually would but was otherwise his normal urbane self, he bade her a polite farewell — for they lived in two nearby houses on the same Chelsea street — then he walked home and shot himself.

For the previous four-score years he had always organised his life meticulously, and he approached arranging his death in the same diligent way. He pinned a sign on the outside of his bedroom door — ‘Do not enter, call the police’ — then he lay down on his bed, he reached for his shotgun, and he did what he had planned to do. But his preparation was not perfect at the very end, for he neglected a small detail, the consequence of which I find disquieting yet poignant. He left a suicide note, but he placed it on his bedside table, as a result of which, by the time his body had been discovered the next day, the sheet of paper on which he had written his valedictory message had become so bloodstained that only the words ‘I had no choice’ were still legible.

April was a significant month for him, and not only because he was born on April 13, 1940. His first involvement in motor sport was as a driver — and, although he never raced in a championship Formula 1 grand prix, he entered one non-championship race that could be classified as of F1 status, on April 13, 1969, his 29th birthday. The 1969 Gran Premio de Madrid was run over 40 laps of the then-new Jarama circuit, which measured just 2.115 miles (3.404km), and the sparse eight-car field included two F1 cars, two F2 cars, and four F5000 cars. Mosley qualified his F2 Lotus 59 fourth and retired it just before half-distance with a faulty injector trumpet. It was not the most famous April race he ever entered, for on April 7, 1968 he drove an F2 Brabham BT23C to ninth place in the Deutschland Trophäe. But no-one noticed because that was the race in which the great Jim Clark spun his F2 Lotus 48 and was killed as it smote then ricocheted off the trees that lined the super-fast Hockenheim circuit.