The very first carbon-carbon brakes used in racing were not of the pure carbon-carbon construction as we know them now. Dunlop was concerned about the matching of the thermal characteristics of a carbon disc on an aluminium brake bell and so built a composite disc assembly. This consisted of an inner steel plate with 20 carbon pucks mounted on the surface, ten per side. Unfortunately, this approach did not work, as the differential in the thermal expansion rates of the carbon and the steel caused the discs to deform. Once deformed, they rubbed against the calipers, causing them to overheat and boil the brake fluid.

Brabham went on to team up with another material supplier, Hitco, and solid carbon discs were developed using an aluminium mounting bell that removed the problem of warped steel centres, but Murray and Brabham still had to overcome a host of other thermal challenges. For example, the heat generated during braking led to problems with the surrounding components, such as the wheel bearings, which required the use of cooling vents and passageways in the uprights.

It was not until 1982 that a car equipped with carbon-carbon brakes finished first in a grand prix, that of Nelson Piquet, driving the BT49D at the Brazilian round of the championship, although he was subsequently disqualified for having an underweight car.

For some time Brabham was the only team using its solid, carbon discs, but other teams began to experiment, Bryan explaining. “They were fine at any circuit that wasn’t terribly hard on brakes, it gave you all of the advantages of low mass, low inertia. But the cooling was limited, so they had to swap back to cast iron discs when they went to anywhere hard on the brakes. That was kind of the accepted wisdom, carbon brakes are for easy circuits, cast iron for when it gets tough.”

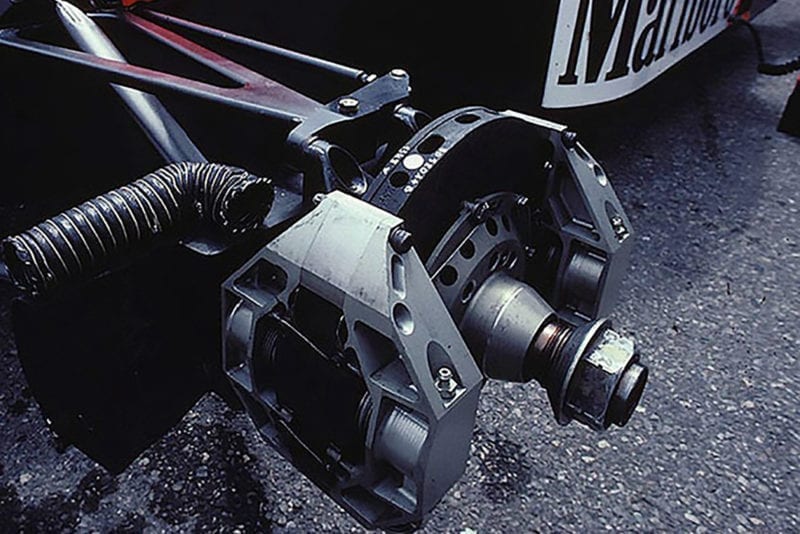

Carbon brake on the McLaren MP4/2 C

It was McLaren that was the first to challenge this established practice, and French aerospace supplier Carbon Industries made them ventilated discs, greatly aiding cooling, which were coupled with an all new, in-house caliper design.

The McLaren calipers employed features such as pistons that protruded from their bores, making the caliper wider and giving a greater air gap between the pad and the caliper. They also used a titanium bridge between machined aluminium cylinders to improve stiffness without adding too much weight.