Motor Sport’s continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson – aka Jenks or DSJ – devoted the first paragraph of his 1973 Belgian Grand Prix report to denouncing the abandonment of Spa, blaming “JY Stewart and his small but vociferous band” for the aberration, ending that vituperative opening par with the words “moving the race to Zolder is such a huge joke that it is no longer funny but depressing in the extreme”.

Nonetheless, a couple of paragraphs farther on, Jenks had to admit that Zolder itself “is not all that bad, exudes quite a pleasant atmosphere, is situated on sandy heathland amid pine trees, and is infinitely more agreeable than Nivelles”. But his bilious resentment towards the disappearance of Spa was evident throughout his Zolder report, and he was annoyed that the agent-in-chief of the removal of “a great and pure road race”, Jackie Stewart, cruised his Tyrrell 006 to victory on the circuit that had usurped it, for he ended his piece with the words… “Stewart just drove away from everyone, the most disastrous Belgian Grand Prix of all time quietly fizzled out, and one had the feeling that, if it was an example of the way grand prix racing is going, then we ought to fold the whole thing up before it becomes the laughing stock of the rest of the world”. You thought journalists moaning about F1 was a new thing? You thought wrong.

The 1973 Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder was a 1-2 for Tyrrell team-mates Jackie Stewart (No5) and François Cevert.

Zolder was and is a pretty decent circuit, actually, and it has changed little over the past half-century. Its first four turns are medium-speed bends that flow together smoothly, then Turn 5 is a dynamic chicane. Turn 6 is quick, Turn 8 tight. In 1973 Turn 7 was a fast right-hander, and it was quicker still in 1982 when the F1 cars that hurtled through it were much more powerful and far more grippy than they had been nine years before.

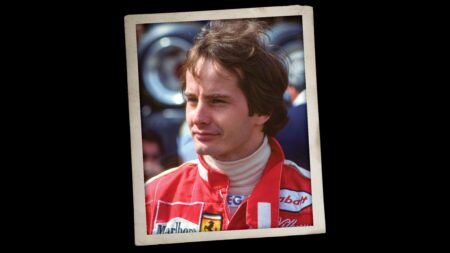

There and then it was that the great Gilles Villeneuve lost his life in qualifying for the 1982 Belgian Grand Prix, and, in an effort to slow things down in the wake of the tragedy, since 1986 Turn 7 has been a finicky chicane. It is now named after him, understandably, but it is not in truth a fitting tribute.