Senna would prevail, but Jordan’s squad had clearly been marked out as an up-and-coming one to watch.

“We so nearly won the championship because we psyched Senna, and he started to make mistakes,” remembered Jordan. “By rights he should have walked it, but it went down to the wire.”

The team would continue competing in British F3, winning the ’87 title with Johnny Herbert, before entering F3000 (then F1’s main feeder series) the following year.

Herbert and Martin Donnelly were the drivers, with Jordan again proving talented at securing the cash needed to progress – coincidentally his team would run in yellow for the first time, a colour it would become synonymous with.

“For the first round in Spain the cars were virgin white, not a sponsor on them, and Johnny put it on pole,” Jordan said.

“Camel were with Lotus in F1 then, but I’d heard they weren’t happy. So I got Camel boss Duncan Lee on the phone that evening and said I’d put Camel stickers on the cars for free the next day, if he agreed to meet me the following week.

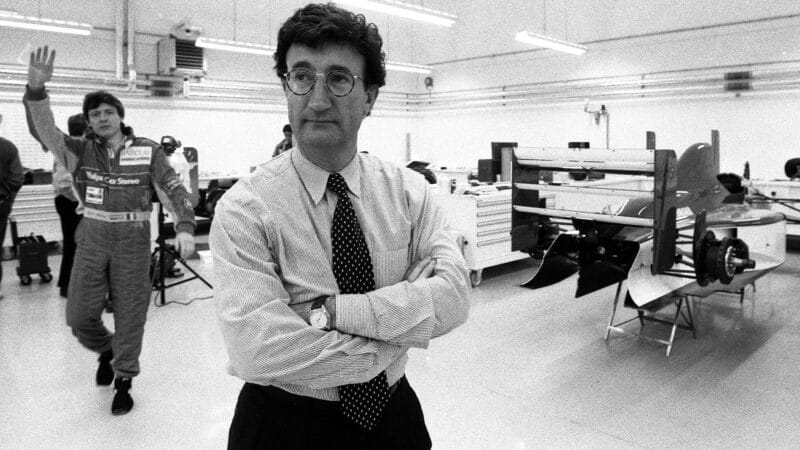

Jean Alesi persuaded Jordan to make the F1 jump

DPPI

“Johnny won the race, and a few days later we got Camel sponsorship for both cars.”

Jordan would win the ’89 F3000 title with a young Jean Alesi, and it was the Frenchman who advised his team boss that an F1 leap was possible after making a number of cameo drives for Tyrrell that season.

“Jean told me, ‘Look Eddie, I can only talk about Tyrrell, but it’s a small team – a bit like what you’re able to do with F3000,’” Jordan remembered.

“He said, ‘I can promise you what we do [in F3000], the way you go about it, the technology, the discipline, the people, the fun, but at the same time the controls, are very similar. I would strongly, strongly advise you to look at Formula 1.’

Jordan took his F3000 team to grand prix racing

Getty Images

Prior to that year, Jordan had told this magazine: “I do not want it to sound as if I am making a casual and boastful comment, but I sincerely believe that I am as good as the people already there and I hope to be able to prove it.”

And so he would – Jordan would assemble what would become one of grand prix racing’s famous crack design teams, that would in turn pen one of F1’s most recognisable cars in the 191, decked out in a 7Up drinks livery. It faced an uphill battle through its first season in 1991 though.