Behra made a great start and led the race until his run was ended at one-third distance by brake problems, after which a hard-charging Hawthorn took over the lead for Ferrari. Moss then passed Hawthorn and spent a short time in the lead before being forced to retire with a persistent and incurable misfire, letting Hawthorn back into the lead. Everyone who had led the race – Behra, Hawthorn and Moss – had done so in a front-engined car. But attrition, exploited by a canny drive from a wise old soul, would change that. In his Motor Sport report, Denis Jenkinson wrote: “On lap 46 nobody was more surprised than Trintignant when he came around in the lead, for the Ferrari had given the appearance of being indestructible, but, no, Hawthorn’s car had come to rest after the descent from the station. This was 1955 all over again, Trintignant driving a model race and profiting from the misfortunes of his faster rivals.” He duly won, thereby making it two grand prix wins out of two for Coopers in 1958, the little rear-engined cars finishing ahead of the second- and third-placed front-engined Ferraris in both Buenos Aires and Monte-Carlo. It is said that it was on the evening of that Monaco defeat that Enzo Ferrari began to wonder whether he might one day have to consider putting the cart (car) before the horse (engine).

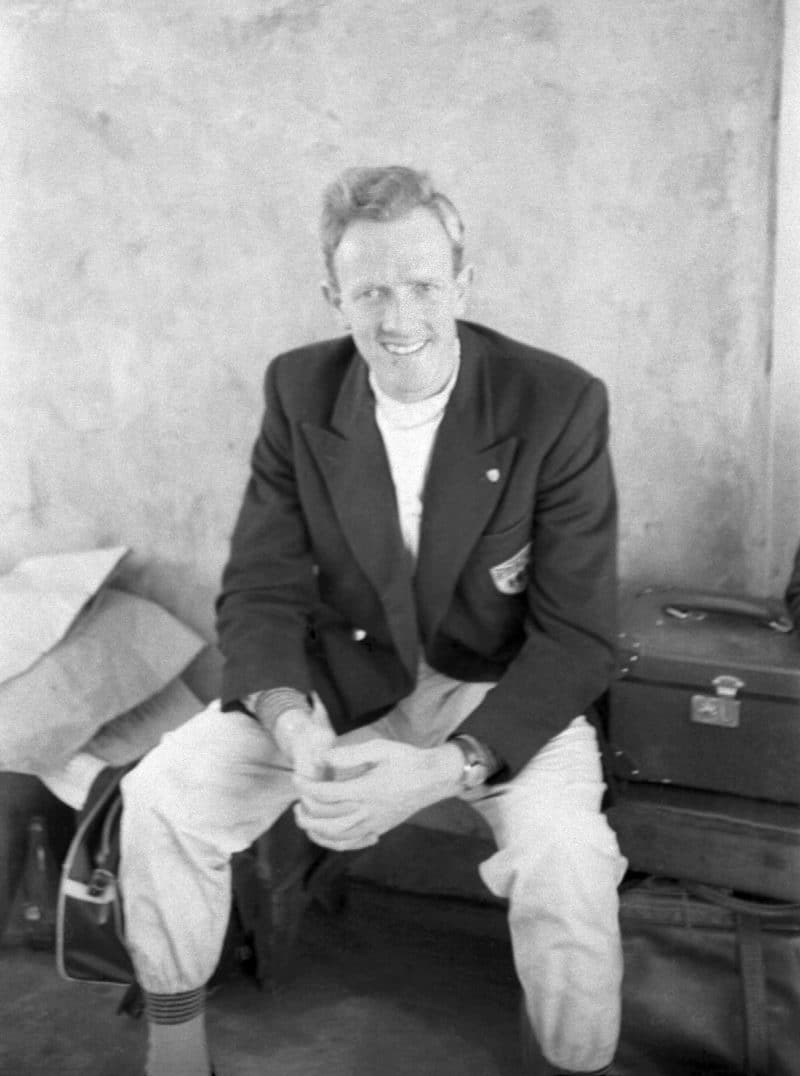

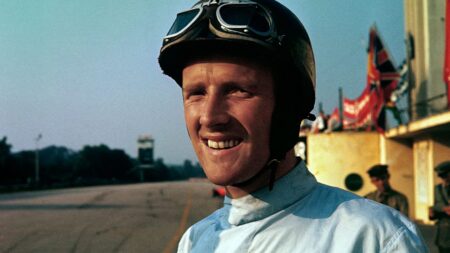

Also present at Monaco that weekend, not unnoticed but little remarked upon, were three Englishmen, including Graham Hill and Cliff Allison, who had both performed well on their grand prix debuts, despite their team, Team Lotus, also having entered a grand prix for the first time. Hill had retired from an encouraging fourth place, stopped by a broken halfshaft, and Allison had scored a world championship point on his grand prix debut, sixth, albeit 13 laps behind the winner. The day before, Allison had been seen welding Hill’s car. Things really were different in those days. Just imagine Pierre Gasly working on Esteban Ocon’s Alpine.

I wrote ‘three Englishmen’ but you may have noticed that I have mentioned only two. The third failed to qualify his ageing Connaught. His name? Bernie Ecclestone. I once asked Moss how good a driver Ecclestone was. ‘About as good as Horace Gould,’ he replied, grinning. Not very then.