The TV executives must have been purring as Hamilton’s mask briefly slipped to reveal a glimpse of his true self, without a crash helmet to shield his state of mind. In the car, he’d remained remarkably composed for most of the previous two and a half-odd hours. Sure, he’d cracked momentarily when Verstappen refused to cede to Hamilton’s clean passing move on lap 37 – “The guy is f***ing crazy, man!” he’d snapped on the team radio – but under intense provocation from a rival who carries an increasingly distasteful over-the-line-and-be-damned approach to battle, the 36-year-old drew on all his vast experience to keep his head, even after their strange collision caused by the Dutchman’s erratic braking.

The mental resilience of top sports people never ceases to amaze, especially today when expressing brutal judgement and vitriol is just a click away for anyone. We all face stresses in our lives and some of us deal with it better than others. Perspective is easy to talk about too, but harder to cling on to, whether your life revolves around something meaningful such as saving lives or something relatively frivolous – such as writing about motor racing! Hamilton, like all top sports performers, has an entirely selfish motivation that places him in this cauldron of scrutiny by his own choice. He doesn’t have to do what he does. So why should we feel sorry for him? Perhaps we shouldn’t. Then again, empathy is a character trait too often overlooked amid the cacophony of the modern world.

Still, even with a bigger-picture perspective, to remain centred in such moments is easier said than done. Whether you’re for Max or for Lewis – and good for you if you’re for neither and just want to watch great motor racing – Hamilton’s ability in this regard should be acknowledged as a major part of his devastatingly effective armoury. But it will be tested again and perhaps to new extremes this coming weekend in Abu Dhabi. He made pointed reference to his dedication to racing “clean” once he did face David Coulthard for his interview and by now it’s safe to assume that if he is to prevail for an eighth time, he will want to do so in a fashion he can be proud of. When you’ve won seven, the details of how achievement is accomplished matters at least as much as the winning itself.

How will Verstappen be remembered at the end of the 2021 season?

Lars Baron/Getty Images

That doesn’t appear to be the case for Verstappen as he strives to avoid losing a first title that looked odds-on and almost in his grasp after his performance in Mexico on November 7, a month ago today. He knows where that line is that he shouldn’t cross – but judging on Jeddah, he genuinely doesn’t care whether he does so or not.

The trouble is those all-seeing eyes won’t miss a moment as they broadcast every moment to our TV screens. It feels forebodingly like we’re headed for a tumultuous dust-up in the desert – but a ‘professional foul’ won’t be tolerated as it was in 1990 and ’94. The onus is on Verstappen more than Hamilton to win this title properly, and the key to unlocking a great sporting story rather than a tiresome controversy is simply in his head. So take a moment, Max – and do so now, not in the aftermath of a dark Sunday evening. How do you want to be remembered after such a thrilling season?

Parallels and otherwise to Sebring 1959

The Abu Dhabi GP season climax will play out on December 12 – by pleasing chance, the same date another shoot-out took place 62 long years ago, at the first world championship United States GP, held for the one and only time at the Sebring airfield circuit in Florida that is better known for its 12-hour sports car classic.

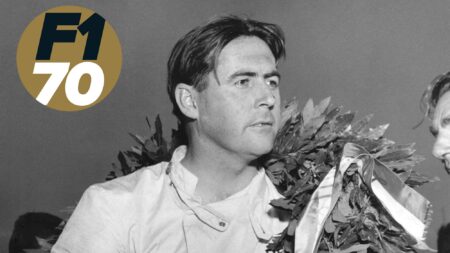

Back then, three drivers arrived with a chance of the title, although Jack Brabham had much less to do than his rivals. The Cooper works driver held a six-point lead over Stirling Moss’s Rob Walker entry, with Tony Brooks also in contention. The Ferrari driver needed to win with Brabham finishing lower than second and Moss lower than third to be crowned.

From right: Stirling Moss, Jack Brabham and Harry Schell on the grid at Sebring

ISC via Getty Images

Formula 1 was still all about drama back then – but not usually melodrama. Although this one had its moments. As Michael Tee’s Motor Sport report tells us, “Harry Schell insisted that he had a better time than he was given and somehow forced the officials to put him in the front row of the grid in place of Brooks.” And poor old Michael Masi thinks managing stroppy Red Bull and Mercedes sporting directors is tough… “A counter argument by Ferrari’s livid team manager [Romolo] Tavoni was unable to succeed in altering the decision, so with a High School band and Majorettes marching up and down in front of the grid, prayers were said, the National Anthem sung and the utter confusion on the start line manually sorted out…” An F1 shambles? Rings a bell.

A sense of anti-climax must have swept across the airfield during those opening laps when the title battle quickly spluttered out. Brooks was the first to lose his chance when team-mate Wolfgang von Trips rammed his Dino 246 on the opening lap and damaged its tail. Again, imagine the kerfuffle of such a thing today. Mind out Sergio and Valtteri… Tony calmly pitted to check for damage and although he re-joined to finish third, a sense of self-preservation in a deadly age cost him a title that he wanted – of course he did – but not at any cost. That’s a bigger-picture view, right there.