Just let that sink in for a minute. Ganley raced this little lot, for starters, and many other fine drivers besides – Jackie Stewart, Graham Hill, John Surtees, Mario Andretti, Emerson Fittipaldi, Carlos Reutemann, Ronnie Peterson, James Hunt and Jody Scheckter – and he regards Amon as greater than any of them.

Andretti’s witty remark about Amon’s bad luck is very well known, Mauro Forghieri’s appraisal of the star-crossed New Zealander’s abilities rather less so. The legendary Ferrari designer/engineer said: “Amon was by far the best test driver I ever worked with. He had all the qualities you need to be an F1 world champion, but bad luck just wouldn’t let him be. He was a driver of the calibre of [Jim] Clark.” There can be no higher praise.

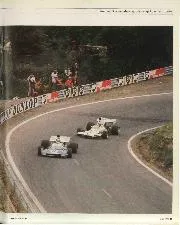

He could and should have won at Watkins Glen in 1967; at Jarama, Spa and Mont-Tremblant in 1968; at Montjuic and Monaco in 1969; at Monza in 1971; and at Clermont-Ferrand in 1972. Matra’s withdrawal from F1 at the end of the 1972 season perhaps knocked some of the stuffing out of him, for he had sometimes been unfeasibly quick in its MS120, one of the most sonorous F1 cars of all time, and no man has ever raced a car more magnificently than he did in that year’s French Grand Prix. Leading effortlessly from pole position, his Matra suffered a puncture to its left-front Goodyear and he had to make an unscheduled pitstop to replace it. He dropped to eighth then charged his way back to third, obliterating the lap record on his way. Yet he never drove a full F1 season again.

Amon (No9) leads at Clermont-Ferrand in ’72. A puncture led to his famous fightback

Grand Prix Photo

In 1973 he raced four grands prix for Tecno and Tyrrell, without any success, and for 1974 he founded Chris Amon Racing, but his Amon AF101, designed by Gordon Fowell and Tom Boyce, was a sluggish embarrassment. He qualified it for just one grand prix, at Jarama that year, and retired it with brake failure at a quarter-distance. He drove a couple of grands prix in 1975, for Ensign, but, although he finished both of them, he did not trouble the scorers on either occasion.

In 1976 Ensign produced a new car, the neat and pretty N176, and, at last, it was heartening for those who remembered just how brilliant Amon had been not that long ago to see him again delivering giant-killing performances, particularly in qualifying, even if his legendary misfortune prevented him from bagging the podium finishes that by rights could and should have been his due. He entered only half that season’s grands prix – eight races out of 16 – yet at Jarama he finished fifth from 10th on the grid, at Zolder he DNF’d from eighth, at Anderstorp he DNF’d from third, and at Brands Hatch he DNF’d from sixth. Pretty and neat the Ensign N176 may have been, but it was too fragile. It may not even have been that fast, for the other drivers who had a go in it that year, Jacky Ickx among them, were never able to make it fly as high as Amon did.

“You have to understand that I didn’t expect to survive my racing career”

Despite all of that, Amon never regarded himself as unlucky. Why not? Because he lived to see the end of his racing career, whereas so many of his contemporaries did not; that’s why not. Over post-lunch coffees at the McLaren Technology Centre I asked Ganley about the ever-present spectre of mortality for the racing drivers of the 1960s and 1970s, and his answer was unembellished by braggadocio yet admirably brave. “You have to understand that I didn’t expect to survive my racing career. I just didn’t. I mean: Jim Clark didn’t survive his; Bruce McLaren didn’t survive his; why would I be so presumptuous as to think I’d survive mine?”

Yet he did. So did Chris Amon, his friend and fellow countryman, who brilliantly but lucklessly raced sometimes fast and often flimsy F1 cars made by Lola, Lotus, Cooper, Ferrari, March, Matra, Tecno, Tyrrell, BRM and Ensign, and his own homespun Amon, too. But cancer he could not survive. He died in Rotorua Hospital, on New Zealand’s north island, in August 2016, aged 73. This year I voted for him to become a new member of Motor Sport’s illustrious Hall of Fame. I hope you did, too.