“Even though I was turning right [at the end of Shoreline Drive], I still looked left, because I could see Clay’s Ensign rushing towards a concrete barrier at undiminished speed. As I rounded the corner, I turned my head to the right again, so as to sight the apex, and at that moment I heard an almighty bang. I was wearing a fire-proof balaclava and a helmet padded with fire-retarding and sound-proofing material, and my Cosworth V8 was revving at high decibels just a few inches behind my back, but, even so, I could still hear the sickening impact of the Ensign smashing into that concrete barrier. Thinking about that sound now, so many years later, the best word I can use to describe it is ‘explosion’. I’ll never forget it. I felt nausea in the pit of my stomach. I was certain that Clay had been killed.”

Regazzoni had not been killed, but he had been very badly injured, and he would never walk again. Even so, he would not only drive again but also race again, for, once he had recovered from a severe bout of depression caused by his initial unwillingness to face a life compromised by such reduced physical capabilities, he found that he could rekindle his old fighting spirit, and he became one of the first disabled drivers to race specially adapted cars in competitive motorsport, competing in events such as the Dakar Rally and the Sebring 12 Hours. In 1994, when he was 55, he even raced a specially adapted Toyota at Long Beach, the circuit on which he had suffered his life-altering accident 14 years before.

He is often remembered for being fiery on track and charismatic off it, and for winning four F1 grands prix for Ferrari and one for Williams, its first. Jody Scheckter said of him: “If Clay had been a cowboy, he’d have been the one in the black hat.” Charismatic and fiery Regazzoni undoubtedly was, and quick too when he was in the mood, but he was also very brave, not only in his pomp, in the heat of fierce on-track F1 battle, but also, and perhaps most impressively, when, newly disabled, he initially felt that life might not be worth living. But he battled and beat that feeling. You see why I am tempted to devote an entire Motor Sport column to him one day, don’t you?

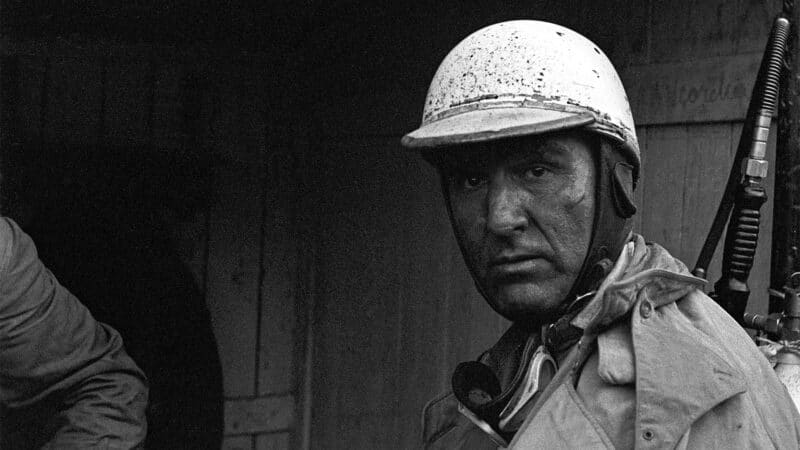

Clay Regazzoni in his Ferrari before the 1974 Dutch Grand Prix

Grand Prix Photo

Three other Ferrari F1 drivers lost their lives on public roads after having retired from racing, and all of them were fascinating characters. Each of them warrants a Motor Sport column of his own — as, par excellence, does Regazzoni, as I say — but this is not that column. I may write those other columns at some point in the future, but we are fortunate that all four remarkable men’s exploits have been chronicled in Motor Sport extensively over the past decades. Anyway, I will write a little bit about them now.

Mike Hawthorn retired as a racing driver at the end of the 1958 season, aged 29, having been crowned F1 drivers’ world champion as a result of finishing second for Ferrari in the last F1 grand prix of the year, at Ain-Diab, near Casablanca, in Morocco. That race was a tragic one, for Stuart Lewis-Evans was fatally injured when he crashed his Vanwall on lap 42. His friend and manager, Bernie Ecclestone, was with him that weekend, and young Bernie lifted cups of sweet tea to his mortally wounded friend’s lips on their long and agonising flight home to England, where young Stuart died six days after the accident. Some time in the 1990s, wealthier by then than in 1958 even he might have dared to hope he might one day become, Ecclestone purchased for an undisclosed sum the Ferrari Dino 246 in which Hawthorn had become the UK’s first F1 drivers’ world champion in Morocco that weekend. I call that an ‘anorak fact’, albeit a sombre and sobering one.

Hawthorn died soon after, on January 22, 1959, on a wet day, on a difficult and dangerous stretch of the Guildford bypass, in Surrey, UK, while driving his heavily souped-up 3.4-litre Jaguar Mark 1 in convoy with that archetypal F1 privateer Rob Walker’s gull-wing Mercedes-Benz 300SL. Hawthorn lost control on a right-hand bend, glanced an oncoming Bedford lorry, and slammed his Jag into a roadside tree so violently that it was uprooted. He was killed instantly. At the inquest the coroner asked Walker how fast they had been driving, but he declined to answer. His refusal to provide that detail prompted press speculation that they had been racing each other. Perhaps they had been, for in later life Walker no longer denied it. In any case a verdict of accidental death was returned.

And here comes a genuinely esoteric ‘anorak fact’. In attendance at Hawthorn’s funeral, which took place at St Andrew’s Church, Farnham, in Surrey, on January 28, 1959 — a bitterly cold day on which the frost never lifted — his former mechanic Hugh Sewell was among the mourners. Sewell, Hughie to his family and friends, had been Hawthorn’s bolter and gofer in his early racing days, and even in his first foray into F1, in 1952, the first of two seasons in which F1 had been run to F2 rules, during which year they had collaborated to campaign an F2 Cooper-Bristol in four championship-status F1 grands prix – Rouen, Silverstone, Zandvoort, and Monza – as well as non-championship F1 races at Goodwood, Ibsley, Silverstone, Boreham, Dundrod, and Reims, winning two of them (the Lavant Cup at Goodwood and the Ibsley Grand Prix at Ibsley). Why am I interested in Hughie Sewell? Because he married my grandmother’s first cousin, that’s why, and I know his children and grandchildren (who are my contemporaries) to this day.

Hawthorn rose to become Britain’s first F1 champion in 1958 – six years after his breakout Goodwood weekend

Getty Images

Giuseppe Farina is most often associated with Alfa Romeo, since it was as an Alfa driver that in 1950 he earned the title of F1 world champion, the first man ever to do so. He won races before the second world war in Alfas, yes, but also in Maseratis, and after the war in Alfas, Maseratis, and Ferraris, too. He scored five world championship-status F1 grand prix victories – four for Alfa Romeo and one for Ferrari – and he finished third in the last world championship-status F1 grand prix he started, also in a Ferrari, at Spa, in 1955.