Alex Waters: the tale of the racer who gave half his funding to charity

He wanted to thank the charity that supported him through cancer - and to fund his budding racing career. So Alex Waters teamed up with Matt Bishop to do both, raising tens of thousands for CLIC Sargeant in the process, with the help of every F1 driver on the grid

Alex Waters raced in F3 after cancer treatment

Alex Waters Archive

On Saturday I travelled to the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) in Birmingham to attend the Autosport International Show, to take part in a panel discussion on behalf of Racing Pride, of which I am a founder ambassador.

Whenever I am at the NEC, I always think of a young man whom I met there in January 2007, when I was hosting and interviewing Formula 1 drivers on the stand of F1 Racing magazine, of which I was then editor in chief. In a break, he approached me. “Hi, I’m Alex Waters,” he said. “I wonder if I could speak to you at some point convenient to you. I’m a racing driver, and I’d like some career advice if possible.”

“I had skin cancer and CLIC Sargent are helping me and my family through that ordeal”

So it was that he and I sat down and he told me his story. He was racing in British Formula 3, he was 19, and he was running out of money. Sadly, there were dozens like him then and there have been hundreds like him since. Such are the perilous vagaries for young racing drivers in feeder formulae unless their parents are minted. On the plus side, unlike many of his rivals, Alex was well presented, very polite and extremely articulate. But that was not what grabbed my attention about him.

No, what inspired me then, and impresses me still, now that I cast my mind back 17 years, is what he said next: “I noticed in the pages of your magazine that you’re doing some fundraising for the charity CLIC Sargent [since renamed Young Lives Vs Cancer]. Well, my F3 car is covered in CLIC Sargent logos.”

Waters drumming up support at the Autosport International Show, 2008

Alex Waters Archive

“Why?” I asked him.

“Because I want to thank them by publicising the great work they do. They’ve helped me a lot in recent years.”

“How? Why?”

“Well, a couple of years ago I was told I had skin cancer, a malignant melanoma, pretty nasty, and CLIC Sargent are helping me and my family through that ordeal,” he replied. I pressed him for more details, and he supplied them. He had been just 17 when he had been diagnosed, he had been racing in British Formula Ford and studying for A-levels at the time, and his treatment had been unpleasant, invasive and stressful. But it appeared that it had worked, for his cancer was now in remission. All being well, he was going to be OK.

It was Eddie Jordan who had introduced me to CLIC Sargent, and that evening I called him to tell him all about Alex. “I think we should help him,” I said, “and I’ve got an idea. Let’s put together a programme whereby we work to get sponsors for him, to fund his F3 drive this season [2007], and the unique element of our offering is this: for every pound that a sponsor gives Alex, he passes on 50p to CLIC Sargent.”

“That could work,” said Eddie, who had sold his eponymous F1 team two years before, to the Midland Group, which had in turn sold it on to Spyker Cars. Nonetheless, Eddie still knew how many beans made five when it came to finding clever ways to create sponsorship opportunities in motor sport. I called Alex to discuss the idea with him, and to tell him that Eddie and I would do what we could to help him, and he was thrilled. He duly agreed to race for Promatecme in the 2007 British F3 championship. He was on his way again.

Waters at Silverstone in 2007

Alex Waters Archive

Eddie and I began to pull strings to see how else we could help him. His race engineer at Promatecme was pretty raw, so I asked Frank Dernie, the legendary F1 engineer, to attend the British F3 race at Oulton Park in early April so as to give Alex and his engineer a hand. Frank was then between two big F1 jobs – he had just left Williams and had not yet joined Toyota – so, being the lovely man he was and is, he agreed. It worked, too. Alex was leading the race until he was taken out in spectacular fashion under the bridge before Deer Leap. Who took him out? Checo Perez, that’s who.

Next, Eddie and Marie Jordan invited Alex to Windsor Racecourse, 20-odd miles west of London, to co-host a charity dinner and auction, the proceeds of one of the lots to be split 50:50 between Alex and CLIC Sargent in the way that we had agreed. It made £60,000: pretty healthy. But we needed more, clearly. So we cooked up another idea. I would ask each and every current F1 driver to draw a caricature of his team-mate, and autograph it. All 22 drawings would be reproduced in a fun feature article in F1 Racing, and the originals would then be auctioned off at the prestigious La Dolce Vita Grand Prix Ball at London’s famous Royal Albert Hall on the Thursday evening before the British Grand Prix.

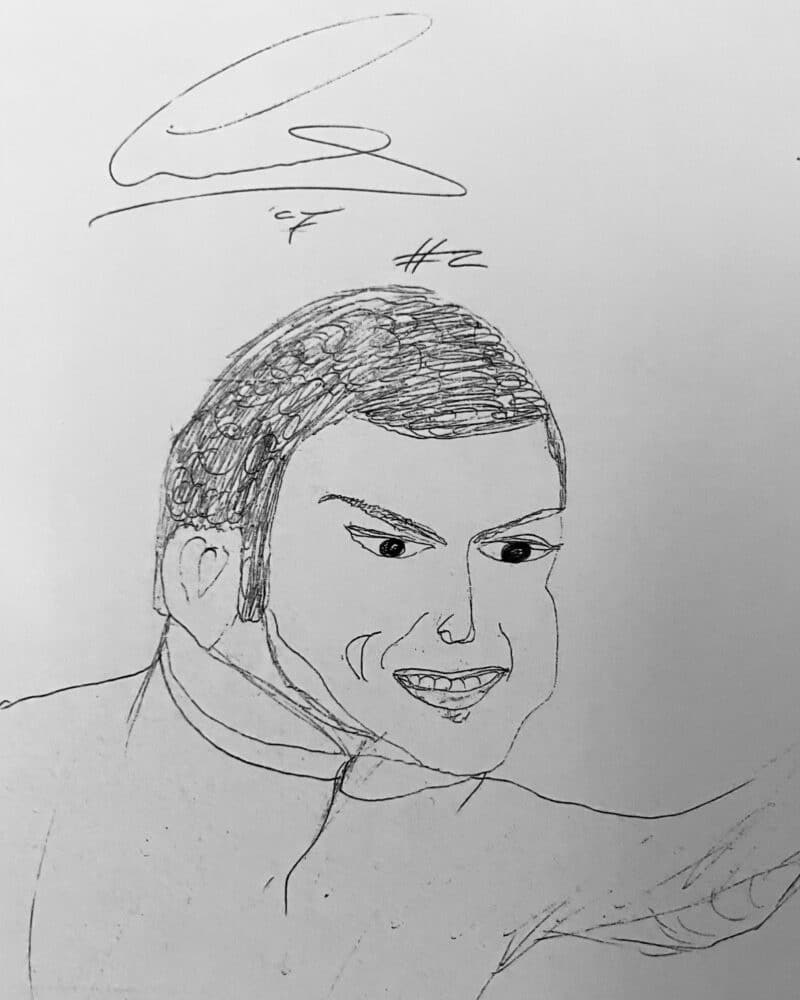

I took Alex with me to the Bahrain Grand Prix, and together we went from motorhome to motorhome, and from garage to garage, traipsing up and down the paddock again and again, never taking no for an answer. In the end we had all 22 drawings safely filed in my briefcase, all of them signed by their creators. I remember many of them even now. Scott Speed caught Vitantonio Liuzzi’s likeness uncannily well. Takuma Sato’s mickey-taking depiction of Ant Davidson was superb. Jarno Trulli’s sketch of Ralf Schumacher, and Nick Heidfeld’s of Robert Kubica, were minimalist and clearly had not taken them long: not long at all. But Lewis Hamilton had agonised over his portrait of Fernando Alonso, and the result captured the mischievousness of the Spaniard’s smile brilliantly. We ran all 22 drawings in the magazine, over eight pages, and the readers’ feedback was sensational.

Bahrain GP paddock tour secured caricatures from each F1 driver

Fernando Alonso by Lewis Hamilton

Anthony Davidson by Takuma Sato

Eddie and I coached Alex in the lead-up to the Grand Prix Ball, but we really need not have done so: despite his tender years he proved to be a natural orator. When the evening came, I was sitting on a table alongside his mother and father, plus a few other friends and associates. As Alex walked on stage, mum and dad both tensed: they were proud, yes, and rightly so, but clearly nervous. He described the collection of caricatures as we had rehearsed. He explained that half the winning bid would go to charity, and half to fund his racing career that was now back on track, literally, but had been interrupted by cancer. He ended with: “…and I hope, ladies and gentlemen, that you’ll bid generously, so that I may carry on my racing career, yes, but also so that other boys and girls, other young men and young women, may live their dreams, as I’m now able to live mine, thanks to the wonderful charity CLIC Sargent.”

How much had we been hoping to raise? It was hard to say. It was an unusual lot, to say the least. Maybe £1000 per drawing? Perhaps £22,000 in all therefore? Yes, that would be a decent result, we felt. The auctioneer, the famous Charlie Ross, began. “Do I have £11,000? That’s just £500 per autographed drawing, drawn and signed by the fair hands of Lewis Hamilton, Jenson Button, David Coulthard, Fernando Alonso, Kimi Räikkönen and all the others.”

The bidding was immediately rapid. Soon Ross was adopting £5000 increments: “Do I have £60,000? Yes, thank you, sir. Do I have £65,000? Great, thank you, madam. Do I have £70,000?” etc. In the end his gavel fell at £120,000. Alex’s mother was in floods of tears. His father was struggling to control his emotions, but eventually he too failed – joyfully. I was absolutely delighted. Eddie ran over from his table and hugged us all. So, finally, when he had walked around back-stage to rejoin us, did Alex, which triggered further tears from the (appropriately named) Waters parents.

“I was prepared to pay £60,000 for something that I absolutely didn’t want”

Suddenly, a chap from a neighbouring table approached me. “Are you Matt Bishop?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Good. I’m Kevin Stanford.”

I am ashamed to say that I did not recognise my interlocutor, but I was later informed that he was (at that time) the majority shareholder in AllSaints, the well known international fashion retailer. “I like what you’ve done,” he went on, “and I think Alex is a really great lad. Super-impressive.”

I expressed gratitude and agreement.

Stanford continued: “Well, yes, so, look, I was bidding for a while, not because I wanted the drawings – I wouldn’t have a clue what to do with them to be honest – but because I was keen to support the boy and the charity. I dropped out at £60,000. Anyway, yes, because I was prepared to pay £60,000 for something that I absolutely didn’t want, in good faith I should donate £60,000 anyway, even though I stopped bidding before the end of the auction.”

And, with that, he took his chequebook out of the pocket of his dinner jacket, and, then and there, he wrote a cheque for £60,000. So, suddenly, the proceeds of our clever little idea had jumped to £180,000 – a lot of money even now and a hell of a lot of money in 2007.

Alex is now 36. No, he did not make it to F1. In the end he finally ran out of money, as do so many talented young drivers from economically normal families. But he had shown flashes of brilliance along the way. He had led a British F3 race at Oulton Park, as I say. He had been quickest in a British F3 test at Pembrey that same year, 2007, then quickest again in a European F3 test, at Valencia, in the wet. He was then selected for a Red Bull Junior Team trial in Formula Renault cars at Estoril – I had previously taken him to see Christian Horner and Helmut Marko to help him state his case – where, despite having zero experience of the cars, which many of his rivals had been racing extensively all year, and although he had never driven even a single lap of the circuit, he ended up quicker than many of them, including his Oulton Park assailant, Checo Perez.

Waters talents are now employed by the likes of Pagani

Alex Waters Archive

So what is Alex Waters doing now? He is an excellent driver coach. He has also done promo work for Aston Martin, Audi, BMW, Ferrari, Jaguar, Lamborghini, McLaren, Pagani, Rolls-Royce and many others besides. He now lives in Golden, Colorado, USA, with his girlfriend Kristin, but, even so, he flew to London to attend my 60th birthday party in December 2022. I have told you his story because he is a lovely guy, and also because it is typical of the frustrating tales of dozens of ambitious and gifted young men and (now) young women whose racing careers come a cropper every year solely owing to lack of money. It is what it is. It sucks.

But, more important than any of that, Alex’s cancer has never returned.