His background had prepared him for just such a role, although he did not know it at the time. A promising teenage ice hockey player in his native Finland, he had tried but failed to make the grade as a pro. Disappointed but undaunted, he threw his competitive enthusiasm at the medical world, entered med school in Turku, south-west Finland, in 1977, and graduated in 1983. First he practised as a doctor in his home country, and soon he broadened that remit to include working with the Finnish Olympic team. But he was religious, too, and gradually he felt a divine summons not only to stay true to his Hippocratic oath but also to combine it with something akin to a crusading fervour. So in 1992 he took the lion-hearted decision to move to Ethiopia, which was at that time not only a wretchedly poor country but was also recovering from a 17-year civil war and multiple droughts, the combination of which had plunged it into a severe famine.

Ethiopia changed him. He saw terrible things there. The experience made him remarkable, perhaps unique. He worked as a doctor, and a missionary too, both jobs forcing him to confront human suffering on a monstrous scale. In addition, ever the sportsman, over time he began not only to work with but also to learn from the country’s world-class long-distance runners. To say that they impressed him would be an understatement. No, he admired them, indeed he revered them. Nonetheless, he was still able to help them. Gradually, the work that he did with them took on a pattern, a shape, and finally a philosophy: he called it ‘the circle of better life’. It came to him one evening, in a flash. He drew a circle and, ranged around its circumference, he wrote the following six locutions: physical activity, nutrition, sleep/recovery, biomechanics, mental energy, general health. Then in the middle he wrote the word ‘core’. It was that circle of better life that he took to McLaren in 1998. It is that circle of better life that the medics of the company he founded, Hintsa Performance, still apply in the work they do today with athletes who compete at the highest level in dozens of sports, including but not limited to F1.

Perhaps he should still be working for McLaren, or Hamilton, now; but he is not. He is not because he contracted pancreatic cancer in the summer of 2015 and died on November 17 the following year, aged 58, which means that this coming Friday will mark seven years since his passing. Knowing that the type of cancer he had was one of the most aggressive, he nonetheless faced it with magnificent courage and good humour. He attended the Italian Grand Prix at Monza just two months before he died, and, although he did not call it a goodbye visit, we all knew that it was; even so, his broad smile and infectious chuckle were very much in evidence, despite the battle that was being waged within his newly slight frame. His funeral took place in Finland, on a bitterly cold day, and in the church I sat next to Pedro de la Rosa, who had grown close to Aki during his time as a McLaren test driver. When Aki’s young widow, his second wife, made a brave and beautiful valedictory speech, one hand on his coffin and the other hugging to her side their two little children, we wept like babies. It was impossible not to.

Aki Hintsa was a wonderful man. Had he not appeared in Häkkinen’s life in 1998, it is fair to say that he might have won no world championships. Instead he won two. Had he not been a steadfast support to Hamilton when he was struggling with tensions with his father on the one hand, disagreements with Dennis on the other, and the overbearing omnipresence of Max Mosley’s menacing FIA, it is fair to say that he might even have quit F1 in some of his gloomier moments in the latter part of his McLaren career. Instead, he has now won seven world championships, or eight, depending on your point of view. But Aki helped all of us McLarenites. Often I would ask him for advice. Always his counsel would be wise. Sometimes it would be brilliant. He was fantastic with our mechanics and engineers, too.

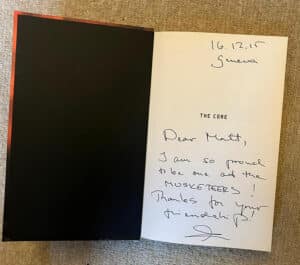

In 2015 the Finnish journalist Oskari Saari wrote an excellent Hintsa biography. Fittingly, he called it The Core. Describing Aki’s resolution to leave McLaren at the end of 2013, which followed a disagreement with then team principal Martin Whitmarsh, Saari wrote: “The decision was made more difficult by the deep friendships he had made over the years. Among the McLaren staff especially Sam Michael, Mike Negline and Matt Bishop were like brothers to him. And then there was Ron Dennis, always Ron Dennis.” Happily, Hintsa and Whitmarsh made their peace soon after their row, but, despite entreaties from Dennis that he reconsider his decision to leave, he would not do so.

Eleven months later he was dead. I miss him every day. RIP Aki Hintsa: the archetypal unsung F1 hero.