Wind tunnels are tricky things, and their most problematic aspect is the correlation — a word that you hear F1 aerodynamicists using many times per hour — between tunnel data and on-track results. Getting correlation right is a science, of course it is, but it is also a bit of a black art. I was McLaren’s comms chief when in 2010 we abandoned our on-site tunnel, realising that it was unfit for purpose for many reasons, including but not limited to poor correlation. For the next 13 years the Woking team used Toyota’s tunnel at Cologne, Germany, and, although the data that it generated was accurate and therefore valuable, the logistical difficulties posed by the 400 miles that separated it from the aero experts whose task it was to crunch that data were considerable. This year has been the first in which McLaren has once again had the use of a state-of-the-art tunnel within its Woking factory, and in my opinion the restoration of that crucial amenity has been and remains a key mainspring of the team’s return to serious race-winning competitiveness.

Whitmarsh also played a key role in persuading Honda to partner Aston Martin in 2026, which will be the first year of F1’s next power unit era. There is nothing wrong with Mercedes AMG High Performance Powertrains, Aston Martin’s current supplier, but Stroll’s ambition is not to match the works Mercedes AMG F1 team but to beat it. To do that regularly and repeatedly, a power unit better than that used by Toto Wolff’s organisation will be required.

Honda will follow Newey from Red Bull to Aston Martin in 2026

Aston Martin

Honda engineers sometimes take their time to get things right – I was at McLaren during the painful years that spanned 2015 and 2017 when they were serially getting things wrong – but with hindsight Zak Brown, Eric Boullier, and Jonathan Neale (McLaren’s then powers-that-be) should have persisted with Honda instead of junking that partnership in favour of an expensive customer deal with Renault. Yes, McLaren-Renault was more successful in 2018, 2019, and 2020 than McLaren-Honda had been in the three seasons before that, but it was not until McLaren had jettisoned Renault in favour of Mercedes that F1 grand prix wins finally began to come again.

Moreover, believe me, Honda knows all about designing and making power units. The Japanese multinational automotive giant manufactures more engines than any other company in the world, producing an average of 14 million per annum – for cars, trucks, and motorcycles, of course, but also for boats, planes, lawnmowers, chainsaws, strimmers, rotavators, tillers, cultivators, pressure washers, hedge cutters, water pumps, generators, and more besides. As Red Bull proved in and after 2019, the first year of its partnership with Honda, Honda would have delivered for McLaren if the McLaren directors had been more patient. Anyway, McLaren’s loss was Red Bull’s, and is now Aston Martin’s, gain.

If he’s as successful at Aston Martin as he has been at Red Bull, he will become F1’s first billionaire engineer

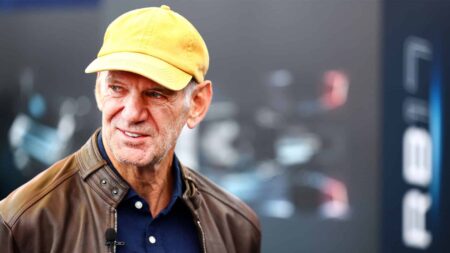

As far as F1 is concerned, Whitmarsh’s job at Aston Martin is therefore done. The factory — sorry, technology campus — is up and running; the wind tunnel build is well underway; and Honda has been contracted. However, ever since he was hired in 2021, his job title has always been group chief executive officer of Aston Martin Performance Technologies, which is a corporate entity adjacent to but separate from Aston Martin F1 Team. Andy Cowell was announced in July this year as Aston Martin F1 Team’s new group chief executive officer, and he will take over Whitmarsh’s F1-related roles and remits. Mike Krack, despite his lofty job title — team principal — has always been junior to Whitmarsh and will be junior to Cowell. Before too long Whitmarsh may well step away from Aston Martin entirely — after all, he is 66 and he was happily semi-retired before returning to F1 in 2021 — but then again he may remain involved with Aston Martin Performance Technologies. The team’s July press release was unclear on that point, including as it did the following quote ascribed to Whitmarsh: “Andy’s arrival in October and the completion of the technology campus will allow me to step away and focus on other projects in my life, knowing that the foundations have been established with an impressive team, inspiring vision, and advanced facilities to achieve success in F1.” In other words, no unequivocal reference to Whitmarsh’s complete departure from all aspects of Aston Martin’s operations was included in the July announcement.

Whitmarsh (right), with Lawrence Stroll, has laid the foundations of Aston Martin’s assault on the 2026 title

Jakub Porzycki/NurPhoto via Getty

Whitmarsh and Newey are not enemies but, despite having worked together at McLaren between 1997 and 2005, they are not friends either. Newey is a genius — by some margin the most brilliant and successful engineer in F1 history, having created winning cars for three teams (Williams, McLaren, and Red Bull) that have been driven to a running total of more than 200 F1 grand prix victories, 13 F1 drivers’ world championships, and 12 F1 constructors’ world championships — and Stroll will pay him a king’s ransom. No, I do not know exactly how much he will earn, or over precisely how many years, but it will be a nine-figure sum and it will be underpinned by hefty equity entitlements and topped up by eye-watering win bonuses. If he is anything like as successful at Aston Martin as he has been at Red Bull, he will become F1’s first billionaire engineer by the time he retires.

His detractors say that he may not be as hungry as he once was. I disagree. At 65, he probably has five good years of full-time employment left in him, and, although he will work very hard for Aston Martin, he will do so in a way that conserves his energy and enthusiasm in a productive way. That is as it should be because, when you hire Newey, above all you are acquiring his thinking, and he needs time to think. He is not particularly adept at managing people, and he does not relish attending departmental meetings or answering admin-related emails, which is why he will be surrounded by other capable senior people who will do that kind of thing for him. What Newey loves, and is best at, is bending his remarkable mind to working out how to win in F1. I will never forget what Dennis once said to me: “Adrian is the single most competitive person I’ve ever worked with.” When you remind yourself that Ron worked with Ayrton Senna, I think you will agree that that is quite a claim.

Newey’s focus is on how to win in F1

Mark Thompson/Getty via Red Bull

Newey’s key colleagues at Aston Martin will be Dan Fallows, who worked well and successfully under him at Red Bull until he was lured to Aston Martin in 2022 as its new technical director; Enrico Cardile, the ex-Ferrari man who will soon join the company as its chief technical officer; and Cowell, whose role as group chief executive officer may sometimes have to encompass shielding Newey, a sensitive soul, from Stroll’s outwardly chummy but occasionally domineering management style. Whether Cowell yet appreciates that, or whether Newey yet realises that it may be necessary, I do not know.

As it happens, the Red Bull and Aston Martin F1 teams share not-dissimilar back stories. Both were originally founded by charismatic ex-driver entrepreneurs. Eddie Jordan launched Jordan in 1991, and it has now morphed via Midland, Spyker, Force India, and Racing Point into Aston Martin; Jackie Stewart launched Stewart in 1997, and it has now morphed via Jaguar into Red Bull. In many ways Aston Martin now finds itself roughly where Red Bull was in 2006, Newey’s first year with the Milton Keynes team and the second year of its Red Bull era.