In 2001, we reunited Allison with the 12. The man from Westmorland was one of Britain’s most promising F1 aces before his career was cut cruelly short by a crash in practice for the 1961 Belgian GP.

The 12 featured such innovations as the ‘wobbly web’ wheels and unconventional ‘queerbox’ transmission, but luckily Allison hadn’t lost his touch.

“It is a bit of a knack,” he told Motor Sport of the idiosyncratic shifter. “In those days I could handle it quite well. It was a positive-stop arrangement like a motorcycle — push down the lever to go up the cogs, flick it up to go down. You just do it with your hand rather than foot.

“It was a brilliant idea — if it could have been more reliable.”

Allison needn’t have worried – in our track test of the first Lotus GP car, it was like the ‘50s F1 hero had never been away.

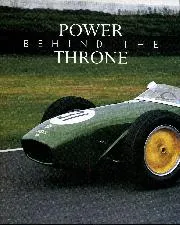

Lotus 18

Heading for victory in the John Davy Trophy Formula Junior race at Brands Hatch in August 1960, Jim Clark at the wheel of his works-entered Lotus 18

GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Another landmark machine, the 18 delivered the first Lotus GP win in the hands of Stirling Moss at Monaco ‘60. it was one that cemented Chapman’s principles of speed through lightness.

The first rear-engined Lotus F1 car, the spaceframe chassis had lightweight body panels attached to it and, in the hands of ‘The Boy’, proved a devastating racing weapon.

The car is incredibly small in proportion too, with just 49 inches between the front wheels – appropriate, then, that Chapman considered this his first ‘proper’ F1 design.