F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

Just over a quarter of a century ago a Japanese company with no record in the field produced a supercar that changed its world. Honda called it the New Sports Experimental, or NSX for short. It contained no new technology and was in fact a very simple thing at heart, but it exploited what was already known with a determination, focus and fastidiousness rarely – if ever – seen in the field.

The result was not just the finest handling, best sounding car of its kind; it was also the most pleasant with which to live. Given the category included the Porsche 911 you can see why it caused something of a stir. It was the car that most influenced Gordon Murray’s design of the McLaren F1, and the car that today some at Ferrari will admit forced Maranello to radically reappraise what was considered to be good enough for this type of car.

And now, you cannot fail to have noticed it has done another. For all Honda’s protestations that the new car has been born in the image of the old it takes no time at all to conclude they are dramatically different machines, even given the 25 or so years that separates their designs. While simplicity informed every aspect of the design of the old NSX, this one could lay a very convincing claim to being the most complex supercar ever to come to market.

Even the way it is built, using a wealth of different grade aluminium alloys, a carbon fibre floor and steel in key areas requiring maximum strength, is fairly bewildering. But what about the powertrain? Here is a car with not one, two or three motors, but four: a single twin-turbo 3.5-litre V6 internal combustion engine tied to one electric motor to remove turbo lag, plus a further two electric motors to drive the front axle and, by varying their relative speeds, deliver active torque vectoring during cornering. It has the world’s first nine-speed double-clutch gearbox and, to keep the whole thing from boiling over, 10 different heat exchangers of various kinds from conventional radiators to intercoolers and oil coolers. It has not only the fly-by-wire throttle you’d expect these days, but fly-by-wire braking too, with no physical connection between your foot and the discs.

It sounds and looks like the stuff of science fiction, but that’s not how it feels when you drive it. In fact perhaps the NSX’s great achievement is the way it is somehow able to marshal all this befuddling technology into a car that drives, for the most part, entirely normally. Yes it has four driving modes from ‘quiet’ to ‘track’ and each one has different settings for sound, steering, brake feel, damping and so on and it will even manage a mile or two on electric power alone, but none of it gets in the way. This is a car that after a really quite brief period of acclimatisation you can get in and drive like you’d owned it for five years.

What does get in the way, at least of the seminal driving experience you are entitled to expect from a Honda NSX, is its weight. The car is quick, but because it weighs 1788kg without weight-saving options like carbon ceramic brakes, it’s not as quick as its maximum quoted 573bhp suggests. When I tested the original NSX for Autocar back in 1990 it weighed 1340kg. What’s more if you take your NSX to the track or merely punt it down an autobahn, you’ll discover it loses 75bhp above 120mph because the front motors shut down to prevent over speeding. Even with its full complement of ponies all rivals from the Audi R8 V10 Plus past the Porsche 911 Turbo S to – emphatically – the McLaren 570S have superior power to weight ratios.

Not that it’s a pudding in disguise. On the track and thanks in no small part to its clever torque vectoring system it masks its mass as well as any I know and proves an able, faithful and nicely balanced companion. But it’s not thrilling. After a while the performance seems almost normal, a fate never suffered by the McLaren, which has just 10 fewer horsepower but over 350 fewer kilos to pull.

Of course Honda could just be being very clever here. Out on the road the NSX is the most civilised car in the category, offering a blend of ride and refinement not even the Porsche or Audi can match. And to those who will buy this car – of whom more will live in America than anywhere else – perhaps these undoubted assets count for far more than on-limit delicacy or high-speed thrust. It may be that the NSX’s target buyer wants a car that looks in the flesh and on paper like a spaceship but whose greatest talent is actually how easy a car it would be with which to live. And that is precisely what the new NSX is and the one thing it truly has in common with its illustrious predecessor.

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

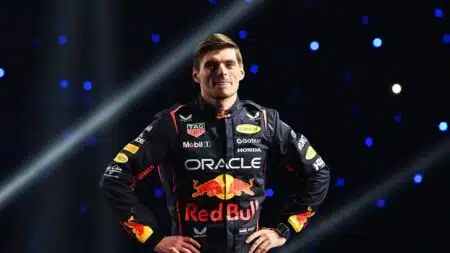

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further