F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

At last it was going to happen. The answer to the most meaningless yet somehow important question of the modern motoring age was about to be provided. On Saturday afternoon at the Goodwood Festival of Speed the three fastest road cars of our or any other generation were to take part in the ‘Supercar Shootout’.

What’s more – and in my view highly courageously – it was going to be timed. For the first time, we were going to find out which was fastest. Best of all for me, I had a ringside seat as McLaren had been kind enough to enter me into the shootout in their special operations 650S.

Except that’s not what happened. First I learned that while there were LaFerraris at Goodwood, they were not Ferrari’s LaFerraris. When I asked why, I was told Ferrari didn’t have any LaFerraris. When I suggested this might be unfairly interpreted by some as Ferrari bottling out of the contest I was greeting with a knowing smile which suggested very clearly the man from Ferrari knew something I did not. And maybe he did. Maybe he knew that when it came to it, no LaFerrari would actually take part in the contest.

Next up was Gordon Robertson, Porsche’s chief driving instructor in then UK and the man entrusted with the 918 for most of the weekend. How fast did he think his car was going to go? “Very fast indeed,” he replied, “for a car running only on electricity…” Imaginatively but infuriatingly, Porsche had decided to do the run on battery power alone.

At least I could count on McLaren test driver Chris Goodwin to make a proper job of the hill in the P1. He was behind me in the queue so by the time I spoke to him we were both at the top and our runs completed. “How’d it go?” I asked eagerly. “Oh, very well. Amazing how fast this thing will go even without the engine running.”

In fact the McLaren only did part of the run on electricity so we can’t even compare the relative pace of the Porsche and McLaren in electric mode (a game the LaFerrari would have been unable to play even if it had wanted to).

The result was the two fastest cars in the supercar shootout were the two slowest cars up the hill and I was not alone in feeling robbed, nor suspecting that all three manufacturers were very happy to ensure the question on so many enthusiasts’ minds went unanswered at the weekend.

So allow me to speculate idly for a moment on their behalf. My money would be on the Porsche being quickest, despite a sizeably inferior power to weight ratio compared to its British and Italian rivals and the reason is simply traction. The four-wheel drive 918 has so much that on battery power alone it was quicker over the first 100 metres than the Lexus LFA that went on to come third over all.

Such is the advantage conferred by all-wheel drive on this bumpy, treacherous course I doubt that for all their extra firepower either the LaFerrari or P1 would have been back on terms by the top. But I really have no better idea than you.

As for me, I decided over 20 years ago that driving as fast as possible up that hill would always carry a level of risk unjustified by the reward. So I made as much noise as possible off the line in the 650S and then drove purposefully but cautiously to the top.

I wound up seventh out of 22 starters which says far more about how easy the McLaren was to drive on that hill than any heroics on my part, of which there were none. Over that weekend at least three of these supercars had substantial accidents, at least one being written off.

The winner of the shootout was Jann Mardenborough in a Nissan GT-R. To give you an idea of how fast was his time of 49.27sec, it would have been quick enough for sixth place in the Sunday shootout of the fastest competition cars, ahead of several F1 machines including a Jordan 191 and Benetton B192 and the six-wheeled March 2-4-0.

All this from a road legal production car on treaded tyres. And, of course, you’d have to bet that either one of the Porsche, Ferrari or McLaren hypercars would have gone significantly quicker even than this had they been allowed to run unrestrained.

Part of me is in awe of the engineering capabilities these achievements represent however irrelevant they may be. But the rest of me wonders more simply where it’s all going to end.

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

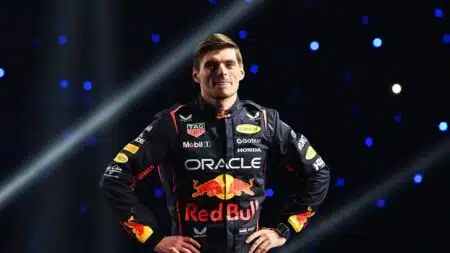

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further