F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

I’m not sure I like the term ‘hypercar’. I first remember seeing it 20 odd years ago when the likes of the McLaren F1, Jaguar XJ220 and Bugatti EB110 took road car performance to a level beyond that of traditional supercars, but the term failed to gain traction. But now with the arrival of the McLaren P1, Ferrari LaFerrari and Porsche 918, I think it’s here to stay.

In fact I wasn’t that sure I liked the idea of not just the word, but the cars to which it is now applied. For all their undoubted technical sophistication, the fact remains these cars are far heavier than those of 20 years ago and because they are hybrids, much of that weight stems from the need to carry two entirely different forms of propulsion that do their best work under different conditions so you rarely reach the optimal point where both are working at peak efficiency together.

Surely these cars are gimmicks, designed as much to confer a sense of entirely bogus environmental good citizenship upon their owners as to produce any kind of ultimate performance?

And just how much additional performance are they providing anyway? Twenty years ago the McLaren F1 had a power to weight ratio of 539bhp per tonne. Today a McLaren P1 provides 623bhp per tonne. It’s more for sure, but is it really that much to show for 20 years, particularly as it’s been achieved only with the addition of almost 300kg of weight? The F1 made a far larger leap over the Ferrari F40 for the addition of just 60kg and did so in just six years.

But last week I went to Dunsfold aerodrome and spent an afternoon driving the P1 as fast as I could make it go, an experience you’ll be able to read about at length in the next issue of Motor Sport. For now however I will say that in one respect the car was largely as I had expected, but in two more entirely different.

What didn’t change was my sense that in terms of ultimate power delivery in the context of the aforementioned ‘hypercar’, hybrid powertrains take more than they give. For instance, if the P1 were equipped with a 4.8-litre engine with the same specific output as its current 3.8-litre motor, it would have more power without a hybrid system than it does with one now; and while that extra litre would add a little to the car’s weight, it would be a small fraction compared to the 170kg it would save by losing the hybrid drive.

Sure the car wouldn’t be able to claim a lower CO2 figure than an Audi TT but who with £866,000 to spend on a car with over 900bhp really pays anything other than lip service to that?

However the hybrid system did something else that I found compelling, and I’m not talking about an ability to drive on electric power alone, though clearly the ability to leave a hotel car park without waking the entire building has some value. Of perhaps greater significance is that the electrics can boost when the turbos cannot, both at low revs and in that pause between your foot asking for the power and the turbos providing it. In the P1 turbo lag simply does not exist. At all. It brings us to the point where engineers can now design an optimum torque curve and then simply programme the engine to provide it.

Of course this is all very well in the far away land of near-million pound mega-cars (is that any better than ‘hyper’?), but there’s no reason why the technology cannot in time transform cars we can afford. The fact is and whether we like it or not, the medium term future of mass market personal transportation will largely comprise of cars with small capacity turbo engines, increasingly with hybrid assistance. If that means all the traditional advantages of turbos can be retained but their drawbacks banished, that can only be good news.

The second reason I think the P1 is of important to more than those 375 people who have bought one has nothing to do with its hybrid system but its ability to change personality more than any other car, road or race, I have driven. At the press of a button it drops 50mm on its suspension and flips its rear wing into a serious angle of attack. So configured it offers downforce comparable to an FIA GT3 race car. Moreover dropping the body doesn’t just increase downforce, it triples the spring rate. So imagine, for instance, how soft a Porsche 911 GT3 could then be set up for road driving, and how much more fabulous it then might feel on the track.

Of course all this technology costs money, but I can remember looking at the McLaren F1’s carbon fibre monocoque 20 years ago and thinking it a technology only multi millionaires would ever be able to afford. But today an Alfa 4C has a carbon tub and costs the same as a mid-sized executive saloon.

The point is the McLaren P1 may only be relevant to 375 incredibly wealthy individual. But in the technology it contains there are lessons to be learned that might one day be relevant to us all.

More from Andrew Frankel

The return of the rear-engined city car

A lambo to love

Has Mini gone too far with its new model?

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

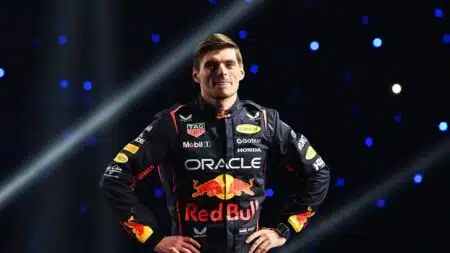

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further