F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

McLaren is just about to launch a road car with more power than its current Formula 1 car. Does that strike anyone else as a little odd?

It says a lot about the times in which we live. Formula 1 cars have less power than they did 30 years ago, a period in which the outputs of the most powerful road cars have more than doubled. But maybe it’s not so strange after all: in 1961 there was no shortage of road going machinery that could overpower the rather puny 1.5-litre F1 cars of the era, the Ferrari 250GT SWB, Aston DB4 and Jaguar E-type among them.

What has changed and will change a lot more are the lengths manufacturers will go to in order to connect what they’re doing on the road with their activities on the track. Of course this is not an entirely new phenomenon either: the straight six in the E-type was sufficiently versatile to win Le Mans five times and for a generation power the country’s favourite hearse. But at the highest level, there has rarely been any crossover at all. From its earliest days if you wanted a front-running F1 car, it had to be so highly developed, so specifically adapted to the simple yet fiendish complex business of driving around in circles as fast as possible that even conceptual crossover to the road car arena was almost impossible.

It was Ferrari, a marque once always late to the innovation party on the racing side – who led the charge from circuit to street. It was the Ferrari that was first to put on sale the first successful robotised manual paddle-shift transmission and Ferrari that has developed steering wheel design to the point where there are more controls on and around the wheel than in the entire rest of the car. It was also Ferrari which bravely bolted the engine of the F50 directly to the tub as a fully stressed member just as had the Lotus 49 in 1967. It even claimed its 4.7-litre V12 was in some way related to the 3.5-litre V12 used by Alain Prost in 1990.

But it is deadly rival McLaren that’s taking the next step. On its steering wheel there are two buttons responsible for rather more than prosaic operation of indicators and windscreen wipers. One is a DRS system, the other the closest you’ll find to KERS on the road car.

The DRS doesn’t open a flap in the rear wing: instead it drops its angle of attack for as long at the driver has his thumb on the button. The other button engages a system McLaren calls IPAS (for Instant Power Assist System) which delivers an additional 176bhp from its electric motor just in case the 727bhp already available from the 3.8-litre twin turbo V8 seems somehow inadequate. Of course it’s not KERS but a rather more conventional system using a lithium ion battery pack and electric motor, but the effect will be very much the same.

What remains to be seen is how Ferrari will answer these challenges. One week before its public unveiling still very little is known about the car with the internal code number F150. We know it too will use hybrid power but that its petrol engine will be a large capacity normally aspirated V12, not a small, turbocharged V8. We know also that Ferrari says its emissions are 40 per cent lower than they’d have been had the same power been created without hybrid assistance.

Of course what nobody knows, not even Ferrari, McLaren or indeed Porsche, whose 918 is cut from similar cloth, it just how popular these hybrid hypercars will prove in the marketplace. One thing is sure: rightly or wrongly the world will soon perceive one to be the most desirable of the three and another the least. And I’d not much fancy being the bloke charged with selling the latter or, to be honest, even the one in between.

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

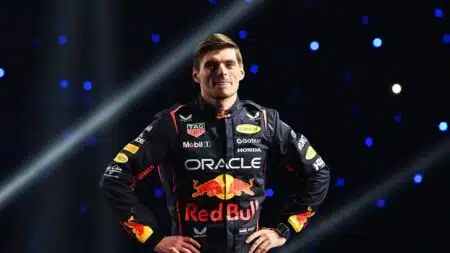

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further