The 100 greatest racing drivers

Greatness in motor sport is more than stats—it's about ability, intelligence, dedication, and impact. Here's our current list of the 100 greatest drivers from F1, rally, IndyCar and elsewhere

Defining the 100 greatest racing drivers cannot be accomplished purely by career statistics. It’s also not simply about pure speed over one lap, stage, stint or race – although clearly that’s a major factor. Greatness, for those of us at Motor Sport, is defined by a heady cocktail: raw ability (certainly), but also intelligence and dedication. Then there’s style, charisma, ethics (or lack of in some key cases), determination and the sheer impact these figures made on their sport and on fans in both their own countries and around the globe. There’s another one too, a big one: versatility – the ability to win in multiple motor sport codes.

We must take in the context of their era, the machinery at their disposal – and also in some cases their ability to work their way into the best drives available. The greats usually drove the best cars – and if not, why not? Beyond the records of titles, wins, poles and fastest laps, it is all utterly subjective – and, some might argue, entirely futile. But lists such as this are a means of focus, of considering when push comes to shove, what and who we value the most, and why.

It’s also just a bit of fun. So in a spirit of good-natured debate among likeminded enthusiasts in love with the greatest sport in the world, let’s not make the mistake of taking it too seriously.

Click to jump to a section, or scroll down for the full list.

| 100-91 | 90-81 | 80-71 |

| 70-61 | 60-51 | 50-41 |

| 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 |

| Greatest Racing Drivers: the top 10 | ||

100-91: Rallying greats and a land speed legend

100 Kalle Rovanperä

It was a marker moment for the man who would become the youngest ever WRC champion in 2022. He repeated the feat with another storming performance in 2023 and then promptly announced that he would compete part-time in 2024, with an eye on using his spare time to go GT racing. A full-time return is mooted for in 2025 when he could well define the current generation as Sébastien Loeb and Ogier did before him.

99 Al Unser Jr

98 Riccardo Patrese

97 Erik Carlsson

Nevertheless, his rise to greatness began on two wheels. In 1947, the teenager acquired a Norton and enjoyed success in hill trials. Five years later, he made his debut as a driver in his native Trollhättan aboard a second-hand Saab 92. His take-no-prisoners style was immediately evident: after cresting a hill, the car went backwards through a hedge and into the garden of a grocer’s shop. Unbowed, he went on to win his class.

His career would go on to encompass a hat-trick of victories on the RAC Rally in 1960-62 and back-to-back triumphs on the Monte Carlo Rally (1962-63). Nevertheless, he cited his proudest achievement as being second places on the gruelling Liège-Sofia-Liège Rally.

96 Craig Breedlove

Of all the record breakers active in what might be described as the most dangerous of land speed racing’s many eras, Craig Breedlove was the one with the closest nodding acquaintance with death. But nevertheless, in a life dedicated to speed, he was the first person to hold land speed records at 400mph, 500mph and 600mph, and survived a 675mph crash, all while he never stopped dreaming about the next attempt.

95 Louis Meyer

The first triple winner of the Indianapolis 500 was Louis Meyer, who won the great race in 1928, ‘33 and ‘36. In fact, he started a dozen 500s between 1928-39. Raised in Los Angeles, Meyer first went to Indianapolis in 1926 as a mechanic for Miller driver Frank Elliott. The following year Elliott entered Meyer in a spare car but it was sold during the month of May and a local driver, Wilbur Shaw, made his rookie start in it instead. Meyer continued as the car’s mechanic and drove relief for Shaw near the end of the race, finishing fourth.

94 Rauno Aaltonen

The crossover between rallying and circuit racing has been surprisingly rare. But in 1966 the current star of international rallying also won Australia’s “Great Race” to earn his place in circuit-racing history. The son of a local garage owner, the teenage Rauno Aaltonen raced speedboats and motorbikes before discovering rallying in 1956. Over the next five years he built his reputation and victory on the Polish Rally and in the Finnish Championship during 1961 confirmed a new star and by 1964 he’d already earned two national titles. The following year was truly Aaltonen’s season – his Mini Cooper S won six rallies across the continent from Czechoslovakia to the RAC to clinch the 1965 European Championship.

The Finn was also expanding his repertoire to endurance racing – driving a factory Austin Healey Sprite at Le Mans and other long-distance classics in 1966. The Gallagher 500 was the first international event in the series that would become known as the Bathurst 1000. He shared his Mini with local driver Bob Holden and took the win after over seven hours on one of the world’s most demanding circuits.

93 Giuseppe Farina

The relaxed stance at the wheel belied the fury with which Giuseppe Farina pushed his car and himself to the limit and often beyond. This was a warrior’s fire and it was stoked with a heady mix of pride and passion, and nothing – certainly not another driver asking for racing room – would in his way. It gave him a long tally of achievement (including the inaugural World Championship) but when up against a Fangio or Ascari it could also see him ask more of himself than he had to give. As such it was a career punctuated by accidents.

92 Richard Burns

The WRC’s Battle of Britain of 2001 is often a title fight forgotten. On one side sat Colin McRae — a certified legend who had first become champion six years earlier — and on the other sat Richard Burns, an underdog in many respects who was about to earn his finest hour. After 18 nerve-jangling miles of Margam Park — the last stage of that year’s World Rally Championship finale — his final result was third place, enough to complete lifelong dream: the World Rally Championship title. An accompanying 10 wins and 34 podiums crowned him as a true legend of Rally GB in a career cut tragically short by cancer.

91 David Pearson

While Richard Petty may be remembered as the greatest stock driver of all time, his nemesis was a reticent understated racer from Carolina: David Pearson. A three-time NASCAR Cup champion with 33 victories to his name, the American was a proven equal of ‘King Richard’ — when he could find a drive — but was always more comfortable with the folks back home in the Carolina mill town of Whitney, where he was born, or Spartanburg, where he lived. He lived a hand-to-mouth existence for his first three seasons from 1960-1962, relying on help from members of the Spartanburg community and a $2000 loan from his father. Later, when he became successful, Pearson often fired up his barbecue grill and hosted lunch at his farm for his working class buddies. He was a true red, white and blue collar racer and remains a NASCAR legend to this day.

Read more

90-81: Racing virtuosos and Ferrari winners

90. Timo Mäkinen

He didn’t say very much, but whatever rally car he was given, Timo Mäkinen could make it talk. For most of the 1960s and 1970s, he was rallying’s John Wayne. Mäkinen walked tall, partied hard and was the fastest man in the joint. In a period before the world championship, he won the most prestigious events on the calendar: battling a blizzard in his Mini Cooper S to win the 1965 Monte Carlo Rally, which was also the year he began his run of three consecutive 1000 Lakes Rally wins. A works Ford drive brought more success, again in the 1000 Lakes as well as another hat trick of wins, this time in the RAC Rally.

When he wasn’t sideways on a stage, Mäkinen competed wherever he could, ice racing; in the Targa Florio; and on the water where he won the 1969 Round Britain Powerboat Race.

He’s remembered as one of the original Flying Finns and his contribution to the world of rallying set a template of success for those set on following in his footsteps.

Read more

89 Jean Behra

Men of the French Resistance were much like Behra; tough-nuts, resilient, self-sufficient, with a love of taking long odds and hearts as big as frying pans. Like Raymond Sommer before him, Behra often swapped winning for the glory of striving for the impossible. When he was good, he was great; like humbling Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari with a Gordini at Reims in 1952. But over-revving his Ferrari in ’59 was part of him too, as was subsequently punching the team manager, and over-committing himself to the south curve at Avus — the final act of his life.

88 Wolfgang von Trips

He was the man with too much desire. As a Count he was able to buy the best apprenticeship. This done, the wildness of youth was replaced by something just as lethal at the time: an aching desperation for success which stretched his high but fuzzily-defined ability into the realms of chance. His sheer bravado in wheel-to-wheel situations took on even scarier proportions when the 1961 Ferrari offered him the cruelly tantalising prospect of a world title. Desire, finally and fatally, tripped him up on the cusp of taking the prize.

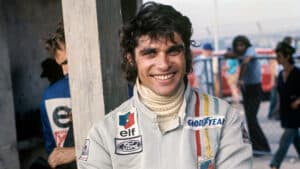

87 François Cevert

With a gift from God and tutelage from Jackie Stewart, Cevert was just beginning to reveal how formidable he was becoming when fate, ambition and a lethally dangerous corner conspired against him at Watkins Glen in ’73. There should have been more, much more, to come. Variously recalled as the most handsome grand prix driver of all, a brilliant classical pianist and an inspirational, warm man being, perhaps he just had too much for this world.

86 Henry Segrave

He dipped into racing in the early ’20s, won at the highest level, then left as suddenly as he’d appeared. Yet there was nothing of the dilettante about Segrave; the concepts of fear and failure seemed alien to him as did the learning curve he was outstanding from the out and won Britain its first international grand prix just a couple of years later. His performances displayed unflinching confidence, determination and judgement, though only sometimes inspiration.

Segrave and arch-rival Malcolm Campbell then began chasing the Land Speed Record. In 1927, it took Segrave to Daytona Beach with his monstrous 1000bhp Sunbeam, powered by a pair of V12 aircraft engines, where he became the first man to exceed 200mph on land. A water speed record holder too, he was killed chasing a new record on Lake Windemere in 1930.

85 Gerhard Berger

A hedonist on and off the track, Gerhard Berger had his natural talent to thank for keeping him out of the barriers during his wild early years in Formula 1: overtaking at 200mph with two wheels on the Hockenheim grass, or overtaking Nelson Piquet at Austria’s fearsome Boschkurve. He joined Ferrari in 1987 after two full F1 seasons; a move that would prove career-changing.

Lap four of the 1989 San Marino Grand Prix and the Ferrari went straight on at Tamburello. Inside, Gerhard knew he was about to die. A second after hitting the wall at 160mph, the car was a fireball. Remarkably, he only suffered mild injuries but the old Berger did indeed die in that crash and a new one was born; the speed was still there but the daring only came with a good reward on offer. However, his 1997 win in Germany in his final season was as ballsy as any.

84 David Coulthard

David was on the verge of something by the end of 1995. He’d got the Williams-Renault finely honed to his driving style and had cast aside the understandable caution of inexperience, liberating his natural racecraft and lightning starting ability. Had his confidence steamrollered from there he could have so easily been the new Niki Lauda; quick, cool, unflustered and always in control of himself and his car. But he went to McLaren where adversity and the speed of his team-mate betrayed his strength as brittle.

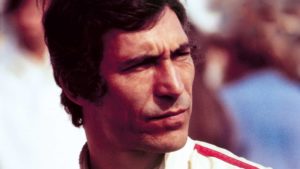

83 Carlos Reutemann

The abstract man. The track was his canvas. On it he executed some of the most breathtaking work ever seen through steering wheel and pedals. There may have been others who matched his balance; but no more than half a dozen this century.

Success beckoned at Williams, but the glory went to Alan Jones who won the 1980 world championship. The pair fell out in 1981 when the title looked to be going Reutemann‘s way until the final race of the season in Las Vegas, where the Argentine fell down the order from pole, ceding his title lead to Nelson Piquet.

Trouble was, his rivals were extras, not really to do with him. Which was fine when he was dominated, but if they strayed into his foreground, his perspective would be ruined. Better to wait for another blank canvas…

82 Didier Pironi

He sold his soul to ambition. He so far transcended his natural limits he believed he could do anything, that the rules no longer apply to him. The apparent check on this ascent – a team-mate called Villeneuve – was dealt with ruthlessly, even by F1 standards. Once Gilles was gone it seemed that Pironi would stop at nothing short of total domination. His commitment, always big, now became scary. That he came shuddering to earth in the most violent way possible confirmed those universal laws still applied, even to him.

81 Robert Benoist

No-one else won a major grand prix in 1927. Benoist’s Delage took them all. Alright, it wasn’t the most hotly contested of seasons and he never approached such success again, but those victories came from a silken style and multiple layers of determination within his small, wiry frame. His reserves of fight and courage really did have no end, as he demonstrated so ably throughout the war until he paid the ultimate price – he was executed by the Gestapo in 1944 as a member of the French Resistance.

80-71: Racing warriors and world champions

80 Parnelli Jones

Parnelli Jones started racing in the rough and tumble world of jalopy and modified stock car racing in southern California in the 1950s. He made his mark by winning in midget and sprint cars before establishing himself as maybe the fastest of all the great drivers who tackled the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in the ’60s — dominating three of the seven Indy 500s he started between 1961-’67 and winning the race in 1963, beating Jim Clark. He built upon his legendary status in the years to come with more success behind almost anything with four wheels and ended his career with seven wins during his run to the Trans-Am championship in 1970.

79 Stefan Bellof

At Monaco in ’84, only his sixth Grand Prix, he bore the mark of someone different. When he then took his outclassed Tyrrell from last to the podium, it was easy to see why. Senna caught most eyes that day, his Toleman about to relieve Prost of the lead when the race was halted, but Bellof was catching them both. If his speed was Senna-like, his fearlessness came easier and he indulged in it for its own sake. A lethal game that ended at Eau Rouge in ’85.

78 Keke Rosberg

The rally man’s racer, he improvised better than Robinson Crusoe. Like when he won at Dallas ’84 on a crumbling track, or set pole at Silverstone ’85 with a slow puncture. Drama. There was always plenty of that once he’d zipped up his racesuit and put out his cigarette. He drove like you’re not supposed to, all harsh inputs and reflexes. But he could bend the car to a will that was tougher than marble and race with a limitless energy. If his tyres were still up to it.

77 Pedro Rodríguez

It was only in the last year that Pedro began properly to fulfil his potential. The pity is his F1 machinery only afforded a glimpse of the ability seen routinely in his Porsche 917. He’d always been gutsy but in the latter days he’d go beyond the margin that defined the limit for others, and stay there for as long as there was petrol in the tank. He was operating in a territory later chartered by Senna when God called his number at the Norisring in ’71.

76 Michèle Mouton

There is no doubt that Michèle Mouton had as much impact on international rallying as the car she drove. Some would suggest her involvement is even more meaningful. Certainly there hasn’t been a woman as capable as Michèle of taking on, and beating, the men at their own game since Pat Moss. And even the legendary Mrs. Carlsson never managed to win as many premier events as the French lady during her ten years in the sport.

The name of Mouton has become synonymous with the Audi Quattro, the car in which she sprang to world fame after scoring four WRC wins — her first coming at 1981 San Remo Rally — and nine podium finishes. She was the first — and hopefully not last — lady of rallying.

75 Olivier Gendebien

The first of the great sports car specialists. This Belgian was a fine grand prix driver, but when he got the chance, he concentrated his energies on endurance racing, mainly with Ferrari. His reward was four Le Mans victories in five years and had there been a drivers’ title back then, he would have won five on the trot! He won all types of events – two Reims 12 Hours, three Targa Florios, three Sebrings and a Nürburgring 1000km – and in a perilous era, his partnership with Phil Hill, forged via the deaths of other Ferrari drivers, was enduring and highly successful. His ability to maintain a metronomic race pace at a time when cars had to be nursed was highly prized.

74 Nico Rosberg

Good looking, articulate and fluent in five languages – Nico Rosberg had it all except for the respect of the Formula 1 fraternity it seemed, despite being the son of F1 legend Keke. The young German was considered to be something of flash in the pan in his early years and even when he more than matched team-mate Michael Schumacher at Mercedes between 2010-2012, the seven-time champion was written off as past his prime.

But when Rosberg went wheel-to-wheel with the super-fast Lewis Hamilton during 2014 and 2015 in identical machinery, one could only admire a previously under-appreciated talent. And the following season finally delivered the World Championship and immediate retirement from the sport – a lifetime’s ambitions satisfied.

73 Luigi Fagioli

A bandit fired by rage, Fagioli was a team manager’s nightmare — he threw hammers around the pitlane, discarded a healthy car when well placed and pulled a knife on a team-mate. But when he directed that rage in the car, he flew with the angels. At Monza in ’32, his trip switch was flipped by inept pit work, and his fightback to second came from a man possessed. That he drove the widow-making Maserati Sedici Cilindri emphasised the violence of it all. They were his finest hours, though some of his later Mercedes drives came close.

72 Denny Hulme

He used what he had so well. He lacked the pure speed of many contemporaries, but he was tough in the head. Which meant that in an F1 career stretching from ’65 to ’74, he barely put a wheel wrong. He never transcended the ability of his cars, but never did less never than full justice either. Often, as in his ’67 championship year, that was exactly what was required. The same toughness allowed him to ignore burnt hands to bring McLaren back after Bruce died.

71 Bill Vukovich

When the flag waved to start the 1953 Indianapolis 500 it was already an infernally hot and humid day with the temperature in the mid-30s centigrade. More than 100 fans and 15 drivers were treated for heat prostration during the day, and only five drivers made the finish without pulling in for relief. In these conditions Bill Vukovich drove without any thought of relief to score a dominant win. He led all the way, save for five laps during the first round of pitstops, and won by more than three minutes. The Russian would repeat the feat the following year and confirmed him as one of US racing’s greatest stars — forever remembered as the ‘Iron Man of Indy’.

70-61: Indy’s maestro and a NASCAR legend

70 Jo Siffert

Fast and dramatic, Jo gave the impression of racing with clenched jaw and tight fists. Often his driving wasn’t pretty, though it was invariably effective in coaxing speed from the car. Combine this with one of the toughest combative spirits to have waited for the starting flag and he could be formidable. There were days when this allowed him to beat Jim Clark, win the British Grand Prix in a private car or dominate at Zeltweg for BRM. But there were days when team-mate Pedro Rodriguez made him look ham-fisted.

69 Malcolm Campbell

From 1924 to 1935, Sir Malcolm Campbell was the fastest man alive. Pilot of the world renowned Blue Bird, the Briton was the first driver to exceed 150mph — a feat he achieved at Pendine Sands in 1925 — and went on to set a new land speed of 231.4mph at Daytona. Five more land speed records followed until Blue Bird flew faster than ever in September 1935, and Campbell became the first driver to ever break the 300mph barrier. With his thirst for speed still not quenched he then turned his attention to the water and later broke the water speed record in the Blue Bird K4 hydroplane which topped out at 141.74mph on Coniston Water in the Lake District. His son, Donald, would pick up the baton and reach unimaginable speeds.

68 Louis Chiron

In his prime, his smoothly deceptive speed blended with wily cunning. Both were on show on his greatest day – Montlhery 1934, where he won in an outclassed Alfa, leaving the presumed invincible teams from Mercedes and Auto Union broken and frustrated. He was vain though, especially in front of his home crowd at Monaco, and this was his undoing as he sought to do what looked impressive rather than what was necessary; he could arguably have won there five times but did so only once.

Chiron lost much of his career to the war, but returned to the race track in the 1950s, and remains the oldest driver to start a world championship race; he was 55 when he entered the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix.

67 Felice Nazzaro

A master at reading a race, Felice would habitually sit back in the early stages, watch events unfold and only when the time was right reveal his blistering speed, turned on like a switch, his Fiat still healthy while the less gentle dropped like flies. He gained the tag of ‘Lucky Nazzaro’ but it had nothing to do with luck, everything to do with an unforced style and the rare ability to direct his passion. In 1907 he won all three major events and as late as the 1922 French Grand Prix was still in winning form, his the only Fiat that didn’t break.

66 Hermann Lang

“Champagne,” said Manfred von Brauchitsch, “oh, and a beer for Lang.” This mechanic-made-good never did hit it off with that particular Mercedes team-mate. But he lorded it over him on the track. Improving like a level-headed apprentice, he gained confidence through experience rather than intuition. But when finally he was ready to pull together all he’d learned, he was fast, focused and, in ’39, close to invincible. The war took his best years but he returned to win Le Mans in ’52.

65 Rick Mears

Without doubt the most accomplished driver of modern times at Indianapolis was Rick Mears. Throughout the 1980s and early ’90s Mears was considered the maestro of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He won four Indy 500s in 1979, ‘84, ‘88 and ‘91 before retiring the following year, as well as taking three CART IndyCar championships in 1979 and ’81-82. He also claimed pole position for the 500 a record six times and started from the front row on five other occasions.

Beyond his superlative record, Mears showed true grit by coming back from a terrible accident at the tiny Sanair, Quebec oval in 1984. He smashed his feet in the crash and it took every ounce of famed orthopaedic surgeon Dr Terry Trammell’s immense skill to repair the damage and get Mears on the road to recovery. Incredibly, despite intense pain and bleeding, Mears was back in action at Indianapolis the following spring and scored his first post-accident victory in the Pocono 500 in August ’85. His injuries remain with him, making it difficult to walk, but Mears never complains.

64 Phil Hill

It remains a quirky statistic that three men named Hill have started a world championship grand prix – and all have lifted the world title. And Phil, the first, is possibly the least celebrated.

Many regard him as a sports car specialist – and it’s hard to brook argument with a CV that includes three victories apiece at both Le Mans and Sebring. The peak of his grand prix success was clouded by tragedy, as the very race at which he claimed the F1 world title also claimed the life of team-mate and friend Wolfgang von Trips. Hill’s GP career rather petered out from there but he continued to compete successfully in sports cars and had the distinction of winning his final race, sharing the victorious Chaparral 2F with Mike Spence in the 1967 BOAC 500Kms at Brands Hatch.

Images of Phil Hill seldom portray relaxation in a racing car, but rather someone who was tense, edgy and acutely aware of his profession’s potential consequences. Someone, indeed, who looks as though he’d rather be almost anywhere else. That, though, was never a barrier to speed.

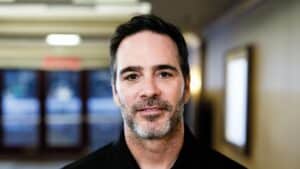

63 Jimmie Johnson

Jimmie Johnson is a true American hero, a NASCAR legend with his own chapter in the sport’s history. Born and bred in California, he was racing bikes, buggies and trucks in the desert when he was still in school and had a Chevrolet contract as a teenager. His dream was IndyCar but Chevy steered him towards North Carolina and NASCAR where he was immediately quick on asphalt, right at home in the big saloons. A long and stable relationship with Chevy and the Hendrick team brought him seven NASCAR Cups, five of them consecutively, equalling the record set by Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt, and two wins at the Daytona 500.

His NASCAR legacy secure, Johnson realised his dream and made the switch to IndyCar in 2020, overcoming initial struggles to race more competitively in his second season.

62 Scott Dixon

Scott Dixon is one of the most successful IndyCar drivers of all time. The New Zealander is six times a champion, has more than 50 IndyCar race wins and has raced 21 seasons with Chip Ganassi, the sport’s longest ever partnership. Having started in karts he rose quickly through the lower formulae, heading not for Europe but to America where he won the Indy Lights championship before graduating to CART with PacWest in 2001. The partnership with Ganassi began in 2002 where his team-mates included Dario Franchitti, with whom Dixon was reunited at the Goodwood Revival, sharing an E-type Jaguar.

61 Juan Pablo Montoya

The son of an architect, “JPM” is blessed with star-quality and natural talent to match. He arrived in F1 amid much hype and with a self-belief that was there for all to see after a Indy 500 victory in 2000. But despite finishing third in the world championship in 2002 and 2003 and with 7 wins, 13 pole positions and 30 podiums under his belt, he decided his future was best-served in America after less than six seasons.

Back-to-back wins at the 24 Hours of Daytona soon followed, alongside another victory at Indianapolis and a IMSA SportsCar Championship in 2019.

60-51: The Great Dane and The Iceman

60 Bruce McLaren

With one leg longer than the other and sporting a permanent limp, Bruce McLaren looked far from a racing legend in his early days. But it did little to deter a fine career. As a driver, McLaren journeyed from local hillclimbs and club races in Auckland to become F1’s youngest race winner in 1959 (aged just 22) and a Le Mans winner with Ford in 1966. As a team owner, with restless ambition, the boss led by example: not only running and racing the cars but also designing and engineering them as well as sweeping the factory floor and driving the transporter. His team found success on the other side of the Atlantic too, with his Can-Am cars dominating the series from 1967-1971.

His untimely death in 1970 after a Can-Am test crash shook the racing world to its core, but nevertheless Bruce’s legacy lives on — his name now synonymous with victory and racing heritage.

59 Damon Hill

The affable Damon is the one who struggled to lift his head above mere competence. Thrust into a leading role after Ayrton Senna’s death, he battled to get on terms with rival Michael Schumacher; a series of errors (and a ruthless Adelaide move from Schumacher) leaving him runner-up in both seasons.

But there’s another Damon in there, one tortured with unresolved questions. When these demons surfaced he faced them off, dug deep into his soul, and left that ordinary man far behind. In those times his inner strength, like his speed, was awesome and he could reach places with ease that seemed beyond him before. The 1996 world champion and race-winner with Jordan could even sustain this level until the questions were seemingly answered.

58 Derek Bell

It’s easy to forget that Britain’s most successful sports car driver had to overcome a long, lean period to accomplish the achievements with the factory Porsche team in the 1980s that projected him to legend status. He had even been toying with the idea of retirement not long before a call-up by the Weissach marque in ’81 reaped a second Le Mans victory alongside Jacky Ickx. As the Group C era was ushered in, Bell scored three more Le Mans wins and two world drivers’ titles, as well as a trio of Daytona 24 Hours victories across The Pond.

Among Bell’s attributes were the ability to pace himself and his car to survive long-distance races unscathed, and mistakes were almost unheard of. But Bell was also genuinely quick in his own right. The JW Automotive team was highly impressed with his speed in its Porsche 917 in 1971, with which he racked up his first two world championship wins. He then led the Mirage team with distinction against the odds in the mid-70s, and it was a great endorsement for him that Ickx asked for Bell to be his co-driver for their ’75 Le Mans triumph.

He was tailor-made for the Group C era, though, his fuel-saving expertise complementing his smooth speed, and he scored 13 wins with Bellof and Stuck, as well as 19 IMSA victories in the USA. And when the hammer needed to go down, as with his last-ditch chase of Holbert at Le Mans in 1983, there was still few quicker at La Sarthe.

57 Alex Zanardi

Alex Zanardi’s 44 F1 starts with four different teams yielded just a single world championship point. But that flatters to deceive. He rarely had a settled season and was often let down by his machinery

In American CART racing where he next sought his fortune, he was a different man: Rookie of the Year in 1996, back to back champion in 1997 and ’98. F1 beckoned again but once more he found himself in an out of form car. Rarely a match for team-mate Ralf Schumacher, his Williams contract was terminated after one season.

He returned to CART and was leading at the Lausitzring in 2001 when he was involved in a terrible crash. He lost both legs, but his determination saw him race again in the World Touring Car Championship and win Paralympic golds in both London (at Brands Hatch in fact) and Rio riding a hand bike. Fate dealt him another terrible blow in 2020 when his bike hit a truck, and his recovery continues.

56 Jacques Villeneuve

Don’t talk to Jacques about rules. He dyes his hair crazy colours, sets pole on his debut, wears his suit too baggy, his suspension too hard. But he’s audacious. Though not as fast as his dad or Schumacher was, the 1997 F1 world champion‘s spirit isn’t on nodding terms with such an idea. No-one else on the grid would have made that move round the outside of Michael at Estoril ’97 but for him it was instinct. In such moves you can’t argue with genes, much as Jacques would try to.

55 Tom Kristensen

The greatest driver in Le Mans history, Tom Kristensen‘s record of nine outright wins may never be broken. He won the race at his first attempt, having never seen the circuit until his practice laps in 1997, and racked up victories as part of Audi’s domination of the event in the 2000s.

Kristensen was the master of getting the best from the Audis, which pioneered diesel power. Fast and consistent, yes, but also patient when he needed to be, Kristensen rarely made a mis-step while negotiating lower-category cars or dicing for race wins. ‘The Great Dane’, as he is affectionately known, has also won the Sebring 12 Hours six times, another record.

54 Kimi Räikkönen

Kimi Räikkönen, 2007 Formula 1 World Champion: unconventional, reserved and a fan favourite. Initially known for his blazing speed, the ‘Iceman’ is now just as noted for his laconic one-liners as he is for his on-track performance.

After arriving with a bang in his first F1 stint as a precocious young Formula Renault graduate, Räikkönen eventually claimed the drivers’ title with Ferrari in 2007.

A two-year F1 sabbatical in 2009-2010 involved off-roading in the World Rally Championship and a brief foray into NASCAR, before the Finn returned in 2012 with a remodelled driving style as a ‘safe pair of hands’. It brought the famous reposte, “Leave me alone, I know what I’m doing”, as he won for Lotus. A Ferrari reunion followed, but yielded just one win in five years.

53 Bobby Unser

Brother Al and uncle to Jr, Bobby Unser was an IndyCar legend in his own right, winning the Indy 500 on three occasions and scoring two USAC championships in ’68 and ’74. An additional 35 race wins were enough to convince even F1 of his talent, and he subsequently made two brief appearances on grids for the 1968 Italian and US Grands Prix.

52 Alan Jones

More than any other, he was psychologically airtight. His strength was everywhere, from his shoulders to his belief that no-one, save perhaps Gilles Villeneuve, was worthy or comparison. With a Williams FW07 beneath him, he was out to prove it every single time. Such certainty gave him momentum at the critical instant for the 1980 world champion. Adversaries crumbled like boys. He drove in the same way and if it lacked grace, “what the hell’s that got to do with it?” he would have countered.

51 Jody Scheckter

The seminal moment of Scheckter’s career came in that multi-car shunt he triggered at Silverstone in ’73. Before that, he just possessed speed and a protective shell of arrogance. The driver he subsequently became was one who could instantly assess with a shrewdness bordering on cynicism what was achievable in any situation in or out of the car. Often he was as impressive for the moves he didn’t make but was still blessed with the speed necessary when the cards fell right. It made for someone who couldn’t help winning.

50-41: Racers who had to wait for glory — and those who never found it

50 Ari Vatanen

Although not quite a viral sensation, Ari Vatanen is proof that world titles can sometimes come to those who wait. The Finn had his WRC debut in 1974 but would not score his first victory until 1980, where his natural talent finally broke the seal of what was to come. The following year he became Finland’s first world champion when he drove a privately run Ford Escort to the title — proving to be scintillatingly fast in all conditions. A nasty crash in 1985 sidelined him for almost two years, but after his return he continued to prove his ability and challenged for victories all the way up to his retirement. A dogged determination if there ever was one.

49 Vic Elford

He may only have a modest tally of world championship victories to his name, but look where Elford scored those successes: he prevailed at the Nürburgring on three occasions, and claimed a win on the Targa Florio, too. That tells you everything about his skill and bravery.

Elford called upon unfathomable reserves of determination to produce almost superhuman performances. Witness his comeback drive on the Targa Florio in 1968: he didn’t just break the lap record as he strove to regain time lost to two loose wheels, he destroyed it by more than a minute. And while Rodriguez and Siffert are thought of as the 917 men, Elford was their match in the Salzburg car.

48 Chris Amon

His was a career that demonstrated how greatness and record sheet can remain strangers. His best drives were heady blends of artistry, grit and even science, for engineers rated him as one of the greatest analysts of dynamics – but they invariably went unrewarded through no fault of his own.

He was of the calibre of Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt. Probably a greater driver than most of those who have won grands prix; certainly more gifted than many a world champion. He just didn’t seem to pay much attention to the nitty-gritty of what it took out of the car to maximise his talent in it. Maybe because that would have involved taking himself very seriously. Of having the energy of a star, around which things would orbit. That just wasn’t him.

Only Stewart produced as many virtuoso performances in the period from ’67 to ’72. It is often said Amon went some way to meet his bad luck, but that came later, after his magnificent 1972 Clermont-Ferrand win, after he surrendered himself to fate and a string of unsuccessful drives.

47 Jenson Button

Jenson Button’s long and ultimately successful Formula 1 career included much frustration before fate finally dealt him a winning hand in the most unexpected of circumstances. Victory in the 2009 World Championship with Brawn succeeded years of near misses with Honda, with whom he’d scored his first F1 win but had also developed a reputation of partying harder than he drove.

In the years that followed, the Briton matured and became an even better grand prix driver, burnishing his reputation for silky-smooth inputs and uncanny weather forecasting. He matched Lewis Hamilton’s points tally while McLaren team-mates and finished runner-up in the drivers’ standings in 2011.

46 Al Unser Sr

The late Al Unser Sr’s long and storied career contained numerous remarkable statistics: he was, most notedly, the second of only four men to win the Indianapolis 500 on four occasions. But in 1978 he achieved something that nobody had managed before and nobody has since: he won that season’s three 500-milers – the Triple Crown – at Indy, Pocono and Ontario.

Smooth and measured, Unser Sr was respected and liked by team-mates and rivals alike and a member of the Unser racing dynasty, with brothers Bobby and Jerry who won at the 500 and in the USAC Stockcar championship respectively and son Al Unser Jr — a two-time CART champion and double 500 winner.

45 Carlos Sainz Sr

Monarchs come and go, but Carlos Sainz will always rule the rally stages for many. Winning the 2024 Dakar Rally is the just the latest in the Spaniard’s long line of successes which includes two WRC titles with Toyota as well as three more wins in the Dakar desert. His racing resume could have been even more impressive had luck been on his side, finishing runner-up in the WRC four times — the most heartbreaking loss coming in 1998 as his Toyota expired just 300m from a third title in Croatia.

Known as ‘El Matador’ — more for his uncompromising desire to hunt down and despatch every rival, rather than merely for his Spanish nationality — Sainz transformed rallying’s philosophy with a sensational win at Rally Finland in 1990. Until then, victory on the brutal stage were the exclusive preserve of Scandinavians, and non-native drivers were seen as having no hope.

Now into his sixties, Sainz Sr shows no sign of slowing down with Dakar supplemented by racing in Extreme E.

44 Mika Häkkinen

“Mika Häkkinen was the best opponent in terms of his quality, but the biggest admiration I had for him was we had 100% fight on track but a totally disciplined life off track. We respected each other highly.”

So said Michael Schumacher who regarded the calm, collected Finn as his most formidable on-track adversary, having seen up close how Hakkinen danced his McLaren to the edge then relaxed into the huge talent that cradles his being. The style – overcommitted then living off the reflexes – was Rosberg, Peterson or Rindt. The origin is God; it wasn’t something Mika had to work on. Then there was the self belief; he could be momentarily fazed, but even a near-fatality left his confidence unbruised.

He wrestled his underperforming Lotus to fifth in his third F1 race in 1991; landed a McLaren testing contract then outqualified Ayrton Senna on his race debut for the team. Inheriting Senna’s No1 driver role when the Brazilian left, Hakkinen survived a horrifying accident at Adelaide in 1995, fought Schumacher successfully for the title in 1998 and won it again in 1999.

43 Mike Hawthorn

Though accused of being inconsistent, even his off days were better than most drivers’ best. And on a good day he could reach for the stars, even Fangio. A wild party animal off the track, there was nonetheless a dark recess within him – possibly stemming from the tragedies in his life, or the knowledge he had a disease which meant he was unlikely to grow old and it was perhaps from this that the steely courage of his best performances was plucked.

42 Ronnie Peterson

An automotive acrobat, Ronnie could drive in the red zone indefinitely, make those big slicks dance to his own crazy tune without ever falling from the wire. As such, he could transcend an ordinary car’s abilities – the Lotus 72 had no business winning three times in ’74 – and when tuned into a good one he was devastating. He had a taste for combat too and was unflappable – Scandinavian ice. Couldn’t set up a car for toffee, though, and in bad situations he’d be easy on himself, giveaways that he lacked ultimate application.

41 James Hunt

Inside the twitching mass of competitive energy lay keen, clear-thinking intelligence. Overlay these, add adrenalin and wait for the fireworks. Back to the wall and everything to play for, he was magnificent. The winning – much more than any love of driving a car fast or wheel-to-wheel duelling or even satisfaction of a job well done – was what turned him on. When the tool became blunted, and winning not possible, the challenge of the game evaporated.

40-31: Multiple world champions and a posthumous victor

40 Jeff Gordon

Jeff Gordon started racing aged just five-and-a-half in a “quarter midget” car, and his obvious talent saw him fast-tracked up the ladder. He was racing sprint cars aged 13 — a decade earlier than many future rivals — and six years later won USAC’s midget and Silver Crown championships in successive years in 1990 and ’91. He moved to NASCAR running one year in the second division Busch series. In 1993 he won the premier Winston Cup series rookie of the year title in his first year with Rick Hendrick’s team when he was 22.

Gordon went on to win four NASCAR championships with Hendrick’s multi-car Chevrolet team in ‘95, ’97, ’98 and ‘01. In his 25-year Cup Series career, he has accumulated 93 wins and is ranked third on NASCAR’s all-time winners list to Richard Petty (200 wins) and David Pearson (105). Gordon’s record also includes 77 pole positions, also third on the all-time list, and 761 starts. He’s won the Daytona 500 three times (‘97, ’98 and ’05) and the Brickyard 400 at Indianapolis five times (‘94, ’98, ’01, ’04 and ’14).

39 Jochen Rindt

Among the most deeply competitive souls of all, Jochen Rindt‘s will went places from which only miraculous car control could rescue him. It was often an anguished, angry soul too, and this played its part in creating a driver that demanded a level of performance from his car and those around him, that went beyond the ordinary. It was the mindset of a champion.

He could do absolutely anything with a Formula 2 car – lead from the front or charge from the back or stage-manage a slipstreaming melee – and was the category’s unequivocal ‘King’ in the presence of Jim Clark and Jackie Stewart.

Uncrowned in F1, he joined Lotus for 1969, and was still there in 1970 when the Type 72 arrived. Consecutive victories at Zandvoort, Clermont-Ferrand, Brands Hatch and Hockenheim gave him what looked to be an unassailable lead. Yet, on the verge of reaping the rewards, he lived in fear of where ambition might lead him. Tragically, the fear was justified.

38 Sebastian Vettel

The youngest ever Formula 1 World Champion at the age of 23, Sebastian Vettel spearheaded Red Bull’s dominant period in the early 2010s. By 2013, he had become only the third man in history to win the title four years in a row, following the path of Juan Manuel Fangio and his hero, Michael Schumacher.

He was then aged just 26 and grand prix racing’s biggest records looked to be his for the taking until the dawn of the hybrid era where the Red Bull’s Renault engine was no match for the Mercedes. A move to Ferrari in 2015 brought more silverware but the dominance of Mercedes kept the German from a fifth title. The rest of his career was marked by new challenges and the development of others, before finally retiring in 2022 — putting his family first after a legendary career.

37 Tommi Makinen

Four consecutive WRC titles are probably enough on their own to qualify for a space in this list. But Tommi Makinen’s incredible success at the Monte Carlo Rally — an event which is often used as a true measure of a driver’s ability given its complexity — helps him to stand out amongst the crowd. From 1999-2002, the Finn was undefeated on the famous mountain roads. It’s a streak of success that elevated him to sixth on the all-time winners list and he continued hissuccess as a team principal with Toyota until 2002, becoming the first to win titles as driver and team principal in the process.

36 Sébastien Ogier

An eight-time world champion in three legendary cars, Sébastien Ogier has also won the Monte Carlo Rally nine times for five different manufacturers, proving his versatility beyond doubt. Ogier’s four consecutive titles with VW, followed by back-to-back crowns with M-Sport Ford and Toyota — are edged only by those of Sébastien Loeb, although at this altitude, they really are just numbers. Both drivers would arguably have won more, had they remained committed to WRC. As it is, Ogier has dabbled in WEC, racing at Le Mans in 2022, and maintained a part-time WRC schedule.

35 Georges Boillot

It’s doubtful whether there has ever been a driver more sure of himself, whose strategy and tactics were so audacious, yet who possessed the speed and resolve to justify it all. His shooting-star status – he won on his GP debut in 1912, and was only around for another two seasons – meant we saw just a flare of a phenomenon that should have bridged the eras of Nazzaro and Nuvolari.

Ironically, his greatest days, Lyons 1914, went unrewarded. There, in a Peugeot so unbalanced and wilful that a team-mate as great as Goux could make no sense of it, he took the lone fight to the armada of the Mercedes team. And gave it a fright like it wouldn’t know again until Tazio’s day of days in 1935. His misfiring engine expired on the final lap of Boillot’s finest race, but also his last. He died on May 19, 1916, shortly after his fighter plane had been shot down.

34 Juha Kankkunen

Fast, versatile, calculated; it’s no wonder Juha Kankkunen is often named alongside the WRC greats of Sebastian Loeb, Walter Röhrl, Carlos Sainz and the like. Between 1979 and 2010, the Finn competed in four of the WRC’s five main sets of regulations to date and earned three titles driving a Peugeot 205 T16, a Group A Lancia Delta Integrale and a Toyota Celica. Frighteningly consistent, he also became the first driver in the championship’s history to defend his own title (1987) — a feat made more impressive by the fact that the WRC was its the midst of a transition from Group B to Group A cars.

33 Bernd Rosemeyer

Having never raced a car before, motorbike racer Bernd landed the job of piloting a V16-engined Auto Union, a monstrous handful that scared many an old hand. In his second event Rosemeyer was battling with Caracciola’s Mercedes for victory. In 1936, his first full season, he took the championship.

But they are just the bare bones of his meteoric career. The spectacular successes of 1936 demonstrated his flowing talent, fearlessness and relentless spirit when given a competitive car. His performance in the Eifelrennen at Nurburgring was among the most astounding ever; thick fog blanketed the track part-way through, but Rosemeyer alone barely slowed and won by over two minutes. In 1937, though, his Auto Union was outclassed and then Bernd’s approach landed him in trouble. The parallels with Villeneuve are uncanny. The miraculous victories that season at the ‘Ring, Long Island and Donington came amid spins and crashes, but could not have happened without the very qualities responsible for the incidents.

32 Tony Brooks

His rapport with a car was almost telepathic and with minimal but exquisite efforts Tony Brooks would invariably be the class of the field whenever a track placed a premium on high-speed precision. Which in the late ’50s, was much of the time. At such places as Spa and Monza it came so easy it didn’t seem natural and at the Nürburgring poor Peter Collins fatally over-reached himself trying to operate at Tony’s level.

But he was more artist than fighter and his desire to fight at all costs never quite matched one of the most supreme talents of all. He might have won the 1959 Formula 1 world championship for Ferrari but insisted on pitting at the end of the opening lap at Watkins Glen for a damage check after his car had been hit at the start. Stirling Moss described him as “the most underrated great driver of them all”.

31 Nigel Mansell

His enormous natural speed and boundless competitive spirit were intensified by a lack of recognition by the racing establishment. He was from the wrong side of the tracks, with the wrong accent and didn’t look the part. All of which was a red rag to him. Mortgaging his house to fund his racing career, he steamrollered any reservations, and success emboldened him to the point where his combativeness made him electrifying. With respect coming from the crowds rather than the establishment, he began performing for them with searing commitment and bravery.

The anguish of Adelaide 1987, where he was set to win the championship before a spectacular tyre blowout wouldn’t be overcome for another five years, during which Il Leone was adored by the tifosi but fell out with the management during two years at Ferrari, then fought but lost to Senna in the 1991 season.

It was all paid back in 1992 when, paired with the revolutionary Williams FW14B, Mansell swept to a dominant championship, then left F1 entirely and repeated the feat in IndyCar the following year. The less said about his F1 comeback with McLaren, the better.

30-21: The icy lone warrior and a man in black

30 Achille Varzi

Achille Varzi‘s competitive desire burned so hot yet was executed with icy chill. A lone warrior, he narrowed his eyes, assessed what was necessary and ruthlessly homed in. His style behind the wheel was clinical and cool, laser-precise and fortified in battle by a relentless will. His nemesis was Nuvolari, and it speaks volumes that Varzi was not overwhelmed by such an irresistible force. Victory at Montenero ’29 and at Monaco ’33 after a sensational battle with Nuvolari for most of the 99 laps showed he was not to be overawed by the great man.

Keen to avoid direct comparison, though, he moved on whenever Tazio joined his team and later had it as a condition of employment that he would not countenance him as a team-mate. Was that a natural winner’s strength or the betrayal of an inner fear?

29 Dale Earnhardt

Dale Earnhardt was motor racing’s archetypal ‘Man in Black’. Through the late 1980s and ’90s Earnhardt cultivated and projected his image as one of NASCAR’s toughest guys, always ready to use the fender when necessary. He drove a black Chevrolet with a white No3 on the roof and doors, and most of the time he seemed to wear a smirking grin beneath his trim, drooping moustache. The results of his toughness spoke volumes of his talent, as Earnhardt notched up seven NASCAR Winston Cup titles — equalling the record of King’ Richard Petty — 76 Winston Cup victories and $41m in prize money, plus a staggering 25,000 laps in the lead.

His hard-nosed approach to racing earned him plenty of critics but a legion of fans along with it. A blue-collar background and non-PR friendly approach to his racing burnished his reputation.

28 Walter Röhrl

Possibly the best rally driver of all time, Walter Röhrl’s very special blend of sublime talent, unswerving focus and brutal honesty ensured his title-winning years were less than serene.

He carefully selected the events he contested — for example, he never competed in Finland because it wasn’t one of his favourites — but measured his own success by how many times he won in Monte Carlo, given the event’s difficulty. He won in the Principality four times behind the wheel of four different cars and left the championship in 1987 as one of the greatest to ever slide on dirt, snow, tarmac and everything in between.

27 Dan Gurney

He should be remembered as the man in the ’59 Ferrari fighting for victory in only his second Grand Prix. As the cutting edge who brought success to the otherwise blunt Porsche F1 effort in ’62. As the man in the Brabham making Jimmy Clark wonder how in hell is that thing so big in his mirrors. He’d been downwind of the pollen of genius at some point, a gift he meshed with a wonderful tenacity in battle. Yet it was as if he never quite believed just how good he was, forever tinkering in chase of a lap time he could have left to his talent.

26 Nelson Piquet

Nelson Piquet was the man who left the mountain and withered away in the denser air below. On a good day, in the early ’80s, Nelson in a Gordon Murray Brabham was the gold standard. Those two components locked into each other tighter than a crown-wheel and pinion, and no-one could disrupt their synergy. He was as fast as the car, which was very fast, and smarter than a boxful of tuxedos.

The first championship came in 1981, as title rival Carlos Reutemann faded in Las Vegas; the following season was spent perfecting the switch to turbo power and it paid off in 1983 when Piquet became the first turbo-powered world champion.

It was downhill from there for Brabham and Piquet jumped ship in 1986, leaving the Brabham haven for Williams, alongside a feisty Nigel Mansell, where his resolve was tested and found wanting. He’d had it too easy with his guardians on the mountain. Even so, despite a heavy crash at Imola in 1987, Piquet raced on to a third world title.

25 Jacky Ickx

The prodigy. He came to be damned by that summary because he never realised the potential laid bare at the Nürburgring in ’67; third quickest in an F2 car! Though there were many demonstrations of his car control and tough mentality over the years – and his wet weather performances were sublime – he was never in a position to sustain such form. He wasn’t enough in love with success to pose a threat to Stewart and by his early 30s, with two runner-up positions in the championship, the inner spark had dimmed.

At least it had for grand prix racing. His first Le Mans win in 1969 was followed by five more in the 1970s and 1980s, when he also began racing int he Paris-Dakar; winning in 1983. Retirement came after an epic 32 seasons in the sport.

24 Jack Brabham

Black Jack probably didn’t even know there was only meant to be one line through a corner – he had loads, and they all worked. Not that he was about to discuss it as he lived in his own world, occupied by welding torches and suspension geometries. His very lack of a consistent approach made him all the tougher to race against, and while he lacked the natural speed of some, his cunning, guts and head-down charge more than made up the difference.

23 Emerson Fittipaldi

He kept his Latin fire in a compartment, to be used sparingly as fuel for his ambition. Emerson was nothing if not smart and mature. This and flowing precision at the wheel led to a meteoric career, and in 1972 he was the youngest ever world champion. Thereafter, he drew steadily less on his speed, and allowed bigger margins into his driving. He never did best his rival Stewart and, alongside Peterson, his response came outside the car rather than from within. It suggested that great though he was, he could have been greater.

22 Colin McRae

Colin McRae, even 17 years on after his death, is the no-holds-barred hero seen to embody all that is good about rallying.

Shots of him flying through the air in his Subaru Impreza, usually sideways, personify a win-it-or-bin-it style, endearing him to the fans and always making him the must-watch rally driver.

That his approach went against the conceived wisdom of rallying probably limited his success – he only won one WRC title – but if his enduring popularity proves anything, it’s that it’s not what you do, it’s how you do it.

21 Richard Petty

As McRae is synonymous with rallying, so is Petty with NASCAR – he isn’t called ‘The King’ for nothing.

Though he is tied with fellow ‘roundy-round’ legends Dale Earndhart and Jimmie Johnson with seven top-tier stockcar titles, it’s Petty who has 200 race wins to their 76 and 83 respectively.

Petty comes from a great NASCAR dynasty, his father Lee being the first three-time NASCAR Cup champion. However, it was his son Richard who won the inaugural Daytona 500 in 1959, now an iconic race and the definitive NASCAR event – he would eventually end his career with a record seven wins there.

20-10: Modern greats and cult heroes

20 Gilles Villeneuve

Never have statistics misled so radically. The brevity of his career, too much uncompetitive machinery and his absolute refusal to accept defeat have seared in many minds a memory of a brilliantly gifted but uncontrolled driver. Wrongly so. The qualities so often cited as reasons for a lack of ultimate track record would under different circumstances have been the cornerstones of fabulous success.

His natural speed — 9sec faster than anyone in the wet of Watkins Glen in 1979; putting a tractor of a 126C Ferrari on Monaco’s front row when the next fastest man of the time, Pironi, was 17th in a sister car — allied to searing competitive intensity, saw him often pull off the impossible. Deprive such a man of an equal playing field and for each feat there will be corresponding drama. Had his career gone its full course and he found himself in better cars, days like Jarama ’81 and Watkins Glen ’79, where his restraint and control were sublime, would have become the norm. Don’t judge him on snapshots of tightrope drama; marvel instead that sometimes more than anyone but Nuvolari he pulled off the miracle.

19 John Surtees

Big John took the hard road. He refused to accept something couldn’t be done, whether it was making the transfer from two wheels to four, beating Jim Clark on equal terms or making a team see things his way. He took on everybody and everything. Some said he had a chip on his shoulder but, if so, it was their snobbery that created it as he made his way without privilege. That will made for a giant of a driver; brave yet circumspect, sensitive but tenacious. But he left Lotus and Ferrari and the glory days passed too soon.

18 Graham Hill

He was the perpetual bogeyman of his rivals’ nightmares; the double world champion who just kept coming back at them, who would never stay down. There was an invisible spring connecting him to the back of whoever the pacesetter was, one which didn’t go soft until after his Watkins Glen accident in 1969. Whatever level someone else set, he could, given time, usually match it. Sheer will rather than pure talent. Sometimes, and five times at Monte Carlo, he’d use his spring to catapult ahead and stay there.

17 Fernando Alonso

He was the youthful sensation who burst on to the scene in 2001 with Minardi. He won in his second full season and was world champion two years later.

Then came a move to McLaren and a bad-tempered clash with Lewis Hamilton; a swashbuckling move to Ferrari that failed to deliver a championship; and then disastrous years back at McLaren.

But after winning twice at Le Mans and running competitively in the Indy 500, Alonso has rewritten his F1 history with a comeback that yioelded eight podiums for Aston Martin in 2023, and reminded everyone of the relentless hunger, and exquisite racecraft that made everyone sit up the first time round.

16 Max Verstappen

The youngest driver ever to race in Formula 1, Max Verstappen joined the grid aged 17 and has grown in the public spectacle of grands prix.

His aggressive manoeuvres brought complaints from other drivers, but Verstappen also delivered, scoring points in his second race for Toro Rosso and winning on his debut for Red Bull.

While team-mates have struggled with various incarnations of the car, Verstappen has rarely looked ruffled by the varying demands of each year’s Red Bull, proving masterful at adapting his driving style to extract maximum performance.

Now three world championships in and a long-term contract with Red Bull, where does this winning machine stop?

15 Rudolf Caracciola

We’re only talking of small margins, but by the time of his biggest successes – the Silver Arrows Mercedes years – Rudolf Caracciola actually lost some of his edge. That extraordinary sparkle was more visible before his wounding shunt at Monaco in ’33. He beat the Alfas and Bugattis at Nürburgring ’31 with a ludicrously unsuitable SSK – aided by the rain which always accentuated his caressing feel – and led at Monaco in ’29 with the same car. Then came his sensational impact with the Alfa team, instantly operating at Nuvolari level. When he made his comeback, his cars were so formidable he was vastly successful, and his miraculous wet weather skills never left him. But the Caracciola of old would not have needed to work so hard.

14 Alberto Ascari

Like his father Antonio, he was fast, so fast. Some even reckoned him quicker than Fangio. He’d carry the speed into the corner smooth as cream, the car not seeming to recognise its speed and giving him an easy ride all the way through. With a good Ferrari beneath him in the early ’50s he converted this ability into one of the longest race-winning sequences in grand prix history, always leading from the front, sometimes over a lap ahead by the flag. Like his father, he pushed to his limits even when this was was not required.

13 Mario Andretti

The man was a fool for racing, so much in love with it he couldn’t stop. His passion showed in every move he made; the thrill of the wheel-to-wheel fight, the caressing way he had with a car. He was the essence of racer, and the flame lit every second he was behind the wheel.

Maybe it didn’t burn as brightly as the best, but it burned long; it should not be forgotten that Andretti set pole for his first F1 race against Stewart and did so in his penultimate one against Prost, nor that he added to his Formula 1 title with four IndyCar championships, wins at the Indy 500, Daytona 24 Hours and Daytona 500. “I never went racing for the money,” he told Motor Sport. “I did it because of my passion for it”.

12 Sébastien Loeb

The great rally drivers know when to push and when to be cautious and Sébastien Loeb is no exception. It’s just that when he pushes, it’s harder than most. Team bosses rave at the pace and consistency of the Frenchman who won in his first WRC season and didn’t stop.

His intense concentration and dedication to perfection locked out the WRC championship for almost a decade, as he won every title from 2004 to 2012. And then retired. He’s been back since and won, but he’s also claimed victories in the FIA GT Series, the World Touring Car Championship and the World Rallycross championship.

Still evading him, however, is a Dakar win, after three consecutive years of top-three finishes. And that’s just all he has had time for. Consider what else he might have achieved given that he finished second overall at the 2006 24 Hours of Le Mans and set competitive times in F1 tests while winning his WRC titles. A true legend of the sport.

11 Niki Lauda

Even among the sport’s greatest, Lauda stands as an embodiment of what can be achieved by reserves of human spirit usually untapped. His accomplishments were of a previously unimaginable scale – whipping Ferrari’s long-squandered potential into world-beating shape, corning back from near death. At the track he was quick and unflappable, but he won many of his Ferrari races well before race weekend. By the time of his third title, much of the speed was gone but that simply laid bare the colossal scale of his other resources.

Motor Sport‘s ten greatest racing drivers of all time

Click on an image to jump to each entry, or scroll down for the full list

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

10 AJ Foyt

If you put him in, almost invariably AJ Foyt would win it. One of racing’s most successful ever drivers is quite simply a force of nature.

Seven IndyCar titles. 67 IndyCar races wins – including a record-tying four Indianapolis 500s, half of which came as a constructor too.

He also won the ’67 Le Mans at first attempt with minimal testing and taking on the share of the driving. Oh, and the 1972 Daytona 500.

If anything, he’s underrated, and the longevity of his career is quite astounding. He first raced in IndyCar in 1957 – and qualified second for the 1991 Indy 500.

“I’ve got false knees, false hips, burns, scars all over my body,” he told Motor Sport in 2015. “I guess I paid the price, the price for always wanting to win.”

9 Jackie Stewart

Motor racing history thrust upon him a seminal stature – Jackie Stewart was The Man who accepted the responsibility of ridding the sport of its gladiatorial excesses. It was dirty and unpleasant but he did it. And the reason he held the formidable authority he did was his towering driving ability.

An outstanding F2 season in 1964 ended with his F1 debut for Lotus when substituting for his hero Jim Clark, who had slipped a disc, in the non-championship Rand GP at Kyalami. He retired on the opening lap of the first heat but underlined his rich promise by coming from the back of the grid to win Heat Two.

Stewart opted for BRM over Lotus in 1965, winning the International Trophy at Silverstone and his first World Championship race at Monza, to finish third in the standings behind Clark and Hill. He began 1966 with a Monaco Grand Prix win, a week before low oil pressure forced his retirement from the lead of the Indy 500 with eight laps to go. Poor reliability and a crash at Spa that left him trapped in a pool of oil with a broken collarbone put Stewart out of contention and ’67 was little better.

That brought Stewart to Ken Tyrrell’s new team, running Matra chassis, and an historic partnership was formed. He clinched a famous victory at a wet and fog-bound Nürburgring by more than four minutes, and came close to the title. The championship was his in 1969 and two more would follow as Ken turned constructor and built his own chassis.

Stewart should have bowed out on a high, having secured his final world title and won safety improvements including larger run-off areas, better barriers, a dedicated medical unit, full-face helmets and seatbelts. However, his charismatic team-mate and intended successor François Cevert crashed and was killed at Watkins Glen. The team pulled out and Jackie Stewart entered retirement.

The cerebral dexterity which had allowed him to compartmentalise the conflicting pulls of safety crusader and racing driver showed in a cool analysis that could instantly nail what was needed from car or self. The qualities ranged from the steely courage of that victory in the ’68 Nurburgring rain and fog to the precision and flair of Monaco ’71 – with a best race lap a second under the pole despite having front brakes only.

8 Alain Prost

The hand is faster than the eye. Alain Prost could conjure a lap time without any outward manifestation of speed. There are those at McLaren who swear that with a perfect car he was faster than Senna, but that more often there wasn’t time for perfection, and that was when Ayrton’s improvisation held sway.

But speed was only one element of Prost’s skill. His awareness of what was needed covered all frequencies, and often, like Lauda, the depth of his intellect ensured that his best work was done before the race weekend. Once there, he could read a race like a book, and if ever there’s been a racer kinder on tyres his name can only be Clark.

Still many view Prost’s career through the prism of his duel with Senna. “It looks like it stays that way for ever, it is part of the history,” Prost told Motor Sport recently. “I had five world champions as team-mates, so it is a bit of a shame. But it is the way it is.

“I do ask myself sometimes how I am going to be remembered. It sounds like a joke but I’m completely underrated! I know that. I can see. I don’t know why, but it’s my brand in a way.”

Prost was the most successful driver from an era that included Nigel Mansell, Nelson Piquet and Ayrton Senna. He joined McLaren in 1980 and outperformed John Watson, then moved to Renault for his maiden GP win at his home race in France.

He had looked to be on course for championship success in 1983, but a mistake and an engine failure handed the title to Piquet and Prost was then fired.

It took him back to McLaren, alongside Niki Lauda, who claimed the title that season. Then, finally, 1985 was Prost’s year, and he became France’s first world champion. He retained the title in 1986 but was still searching for a third when Ayrton Senna joined in 1988.

Thee pair head-to-head for the world title and Prost outscored his team-mate over the season. However, with each driver counting his best 11 results, it was Senna’s better win rate (eight to seven) that delivered the title with a round to spare.

Inevitably, having two of the best F1 drivers of all time in a dominant car led to a fierce rivalry and that boiled over in 1989. With McLaren-Honda once more the team to beat, the frosty relationship between Prost and Senna escalated to outright hostility at Imola. They lapped the field with Senna leading all the way but Prost was seething after the race – the Brazilian seemingly having disobeyed a pre-race team agreement.

It was a successful if toxic final season for Prost at McLaren although his third World Championship was only sealed in the most controversial of circumstances. Senna entered the penultimate race of the year needing to win the Japanese GP to maintain any chance of retaining the title. With five laps to go, Senna attempted to pass his team-mate entering the chicane only for Prost to turn into his car. Prost was out but Senna re-joined and won the race, only to be disqualified after the event. That confirmed a third world title for the Frenchman but it was an inglorious conclusion to the year.

Two unsuccessful years at Ferrari followed, then a sabbatical in 1992, before Prost got the plum seat at Williams in a cutting edge car that earned him a third title before retirement and a less fulfilling stint as a team boss.

7 Michael Schumacher

From an era of Formula 1 that was more than ever orientated towards sprints, and with a car that was not always the best, Schumacher pushed – and sometimes crossed – the physical boundaries more frequently than anyone since Gilles Villeneuve. It was an ability supremely adaptable and as multi-faceted as Stewart’s. His wet weather virtuosity recalled Caracciola, his opportunism in battle was Jones-like and his work rate away from the track, applying himself to the details, may even have surpassed that of Prost.

All this gave him many wins that should not have been possible. Or, more specifically, that his opposition should not have allowed.

“He could make any old rubbish go fast, said James Allison, now Mercedes technical director, who worked with Schumacher at Benetton and Ferrari. “It really didn’t matter if the car was ill-balanced or a bit of a pig, he would find a way to drive it round a lap and get pace out of it.

“He was much fitter than the people he was driving against in an era of refuelling-type racing where it’s just sprinty grands prix where every lap is not that dissimilar to a qualifying lap.”

Schumacher’s ability to reel off qualifying-pace laps in his Ferrari years particularly led to incredible success. An improbable three-stop strategy was turned into the winning one by the end, thanks to the German’s unrelenting pace in the 1998 Hungarian Grand Prix.

It wasn’t just the on-track ability that made Schumacher great. Those who worked with him have spoken about an incredible work ethic that only added another layer of armour to the repertoire.

“He was incredibly into the detail and wanting to pore over the day’s work with his engineers and unhappy if he wasn’t spending every hour God sent on the test track,” Allison said.

“He’d routinely finish each year head and shoulders above everyone else in terms of kilometres spent testing and that wasn’t when he was hungry for his first championship.

“That would be after his third, fourth and fifth championships. He was still out there just wanting to pound round Fiorano and Mugello, or anywhere else.”

From a driver’s perspective, it is a similar story, there was never an ‘off’ mode for the seven-time champion. Nico Rosberg has gone up against both of F1’s record-holders, and witnessed first-hand the mentality that Schumacher brought to the garage

“Michael was a psychological warrior,” he explained

“It was incredible learning for me over those three years. And he didn’t even have to make an effort – it comes naturally to him, to try and psychologically get into the head of his competition. And it would be from the morning to the evening. He’d love to walk around in the engineering room topless just to show his six-pack.”

Schumacher didn’t shirk a challenge. After two title-winning years at Benetton, he joined Ferrari, forming a triumvurate with technical director Ross Brawn and team principal Jean Todt, to return the team to glory — and they did. With a haul of records and 91 grand prix wins, Schumacher retired in 2006, but was lured back to the new Mercedes team in 2010 for a three year stint where he showed flashes of his brilliance, but couldn’t outshine his team-mate Nico rosberg.

Great though he is, where was the Prost to his Senna, the Varzi to his Nuvolari? Hakkinen was the only one arguably as quick, but as yet he lacks the depth of supporting qualities. Michael, then, did not have his genius as fully stretched as, say, Senna. But one thing he shared with the Brazilian is the resort to foul-play in split-seconds of desperation, as though he couldn’t believe his own super-human ability could go unrewarded.

6 Stirling Moss

Stirling Moss was one of those very special ones who could seemingly transcend the accepted definition of ‘possible’ and that directly translated into his public standing as he became a ‘name’ reaching beyond the sport in much the same way as did Muhammad Ali in boxing or Pele in football.

Although he last took part in a grand prix more than 60 years ago, this magician of the wheel’s reputation has rung through the generations. The fact that the list of F1 world champions does not feature his name is more an indictment of the championship than of him. Between the time of Fangio’s retirement in 1958 and Moss’s career-ending accident early 1962 he towered above his contemporaries, arguably to an extent never seen before or since. Even the competition would occasionally acknowledge that his skills were of a different order to theirs.

He was more than just a very great racing driver though. He was the embodiment of Britain’s emergence, post-World War Two, as a force that would soon come to dominate international racing for the first time. He and the Formula 500 movement from which he sprang were the seeds of a revolution and it was perfectly apposite that it was Moss who would take the mid-engined Cooper to its first grand prix victory, Argentina ’58. He was already into his fifth year as a competitive F1 force by then, the ‘Boy Wonder’ having built upon his F2 outings with HWM and Alta to be in consideration for a Mercedes seat alongside Fangio in the German manufacturer’s comeback season of 1954.

Ultimately, they considered him still a little too inexperienced for such a responsibility but urged that should he get F1 experience for future consideration there. A privately purchased 250F Maserati in ’54 established him firmly among the elite, only unreliability keeping him from victory at Monza – where he was leading Fangio’s Mercedes and Ascari’s Ferrari. A ’55 place at Mercedes duly came his way, the basis for not only his first Grand Prix victory – at Aintree – but also his legendary triumph in the Millie Miglia sports car race (with pace notes supplied by Motor Sport’s partnering Denis Jenkinson), a performance since described as ‘the most epic drive ever’.

Moss remained uncertain about whether he really had defeated Fangio at Aintree ‘55 or whether it had been a gift, despite the Argentinean champion’s assurances to the contrary and that Moss had beaten him fair and square. But generally Moss was the pupil, Fangio the master (in F1, at least), the pair separated by 20 years and different languages, though united by total mutual respect. In a sports car, there was little question Moss was the faster of the pair and his career would include major sports car victories in Jaguar and Aston Martin machinery, not to mention innumerable successes in GT and touring cars, even rallying.