Miller’s company would go on to dominate oval racing in the US through the 1920s, producing a range of jewel-like, supercharged straight eights. Miller-powered entries made up an impressive 83% of the field at the Indy 500 between 1922 and 1928. However, by the end of the 1920s, the regulators had become weary of Miller’s pre-eminence, and hoping to attract the major automakers back to competition, effectively outlawed his engines. This, combined with the impending Wall Street crash and depression, brought his success to a screeching halt. Miller sold the company in 1929, but by the end of 1930, the Miller Production Company as it was by then known, filed for bankruptcy.

However, unbeknown to any at the time, one of the company’s designs was set to seal its place in racing lore. In 1926, Miller had developed a 151-cui marine engine, an inline-4 with twin cams (but two-valve heads) destined for hydroplane racing. It immediately caught the attention of land-based racers as a more reliable and potent alternative to Ford Model T engines (for which there were an array of modifications available, including twin-cam heads). Useful as it was, the Miller Marine was never intended as a racecar engine and in 1930, Goosen drew up a design for the Miller 200, a much lighter and more potent 200-cui four with four-valve heads, aimed squarely at the dirt racing market. The basic architecture of this engine, which was built from the outset to allow for an increase in capacity, would form the core of what would become known as the Offenhauser engine.

During the chaotic years of the early 30’s, Offenhauser had seen the writing was on the wall for Miller and set up his own shop in Los Angeles, with equipment snaffled out of his collapsing former employer in lieu of back pay. Importantly, the machines included many of the vital tools and fixtures needed to produce the Miller four-cylinder engines. In 1935, an Offenhauser-built four, by now displacing 260 cui, won the Indy 500 with Kelly Petillo at the wheel and the name Offenhauser began its ascent to oval racing stardom. By the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour in December 1941, Offy powered cars had won Indy four times.

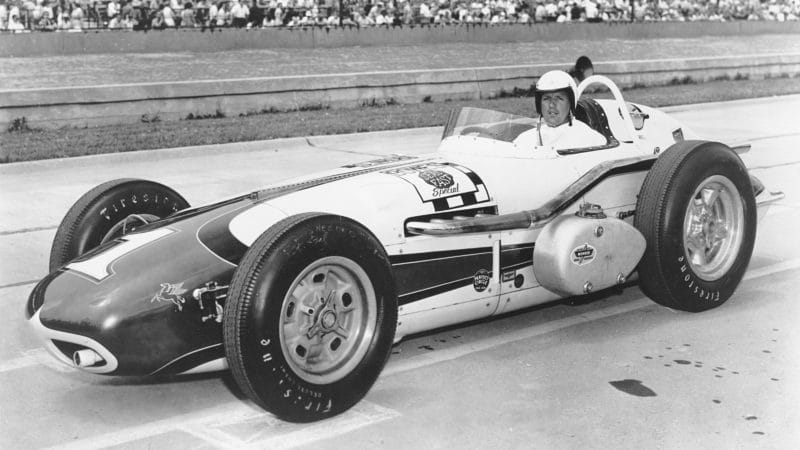

Rear-engine power briefly spelt the end of the Offenhauser dominance at Indy in 1965

Bob D’Olivo/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images

The outbreak of war saw Offenhauser, along with every other machine shop in the States turn to military production, with his shop running 24/7 developing and manufacturing hydraulic booster control valves for Lockhed aircraft. Hostilities would also see Goosen re-join Offenhauser on a full time basis, having previously only worked as consultant. He would go on to draught every engine under the Offenhauser name until his death in 1974.

However, the pressure of war work had taken its toll on Offenhauser and in 1946, he sold up to a partnership of racer Louis Meyer and his long-time ride on mechanic, Dale Drake. It was at this point, the Offenhauser four entered its heyday. The flexible base engine could be adapted to the changing rules at Indianapolis and Offy powered cars went on to win every 500 between 1947 and 1964; astoundingly, between 1950 and 60, they locked out all three steps of the podium. It was only with the arrival of rear engine cars, and Ford’s twin-cam V8 that this winning streak ended, after Jim Clark dominated the 1965 race in his Ford powered Lotus 38. The naturally aspirated Offy’s couldn’t live with the power and fuel economy of the Fords, and ’65 also sounded the death knell of the front engine Indy Roadster – 1968 would be the last year such a design even made the grid.

It seemed the Offy had run its course at the Brickyard, and the company would have to content itself with continued success with smaller capacity engines in Midget racing. However, whereas a change in the rules ruined Harry Miller back in 1930, a similar shift would provide a stay of execution for the Offy four.

A rule change mandating two pitstops and the use of methanol fuel (on safety grounds following a first lap crash in ’64 that killed Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs in the ensuing inferno) in 1965 negated the Ford economy advantage. The rules also allowed for blown engines (either mechanically or turbo supercharged) up to 170 cui, compared to 270 cui for naturally aspirated; theoretically giving a useful benefit towards forced induction.

The Offy was the ideal candidate for pressure charging, not least thanks to its one-piece block and head design removing any gasket issues. Both Roots mechanical supercharged engines and turbocharged units were developed but it would be the latter that proved most potent. In 1968, a turbocharged 168 cui Offy took Bobby Unser to the winner’s step at Indy and by the early ‘70s they were almost untouchable, producing well in excess of 1000bhp and winning back-to-back 500s from 1972-76. Eventually, rule crackdowns and development of other engines would finally seal the venerable motor’s fate, however, it didn’t die easily and the last Offy entry at Indy was in 1983, closing the book on a phenomenal 57-year history.