When we explored the archive, the other section that drew us in was the part dedicated to the gruesome crash at Guidizzolo, less than 40 miles from the finish in Brescia, that kills Alfonso de Portago, his co-driver Ed Nelson and nine roadside spectators, some of whom are children. There is a lot of detail available here and, whether you approved of Mann’s approach to its depiction or not, again it’s hard not to be impressed in how carefully and forensically he and his team approached such a sensitive part of what is after all an event based on the lives and losses of real people.

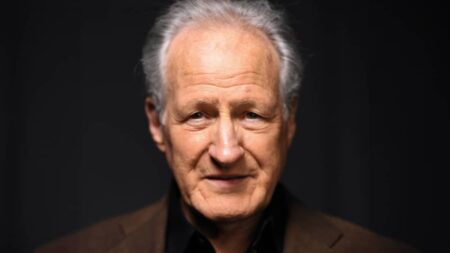

This is a director who has rarely shied away from contextual violence during his long movie career and here he explains why and how he’s chosen an unflinching approach to the terrible brutality of the tragedy – which fully earned the movie its rating as a 15 in the UK. “It’s faithful to what happened, both out of respect and the meaning of that accident,” he maintains.

Motor Sport’s readers will be particularly drawn to the detail made available of the real events: detailed police reports, photos of the actual car and crucially the damaged tyre that caused the accident, and even the stark coroners’ reports on de Portago and Nelson. How the accident was recreated, not just with CGI but with a real car air cannoned into its horrible trajectory, was with a genuine desire for a depiction as close to reality as possible. Mann based his approach on the famous newsreel footage of the Le Mans disaster of 1955, avoiding “a complex montage of different angle that would have been theatrical and would feel artificial”.

He is clearly sincere in his motives, and the archive as a whole opens a whole new and enlightening perspective on the movie-making process. It’s fascinating.

The archive and details of its pricing are available at michaelmannarchives.com