So what’s so magical about carbon-fibre?

That ability to accurately create a chassis that’s light and stiff in some areas and light and flexible in others is what makes it so ideal for MotoGP.

“The fundamental of the material is that you can build something that’s light and strong or light and stiff — many people don’t realise there’s a difference — or light and flexible,” Barnard adds. “You can do whatever you want, depending on how you lay it up, which materials you use and so on.”

Barnard thinks KTM and Aprilia are probably using the M46J carbon-fibre-reinforced-polymer popular in F1.

“M46J pushes you well up the stiffness scale but maintains a very good strength and importantly you can lay it up over fairly complex shapes. If you go to something like M55J, which is super-stiff, you have to be very careful when you’re laying it up, because the fibres are so stiff you can break them.”

But why has KTM’s carbon-fibre frame made the RC16 so much faster out of corners?

Barnard believes the new frame must have more torsional stiffness than the steel unit, so the RC16 finds more drive grip on corner exits, when the bike is close to the vertical.

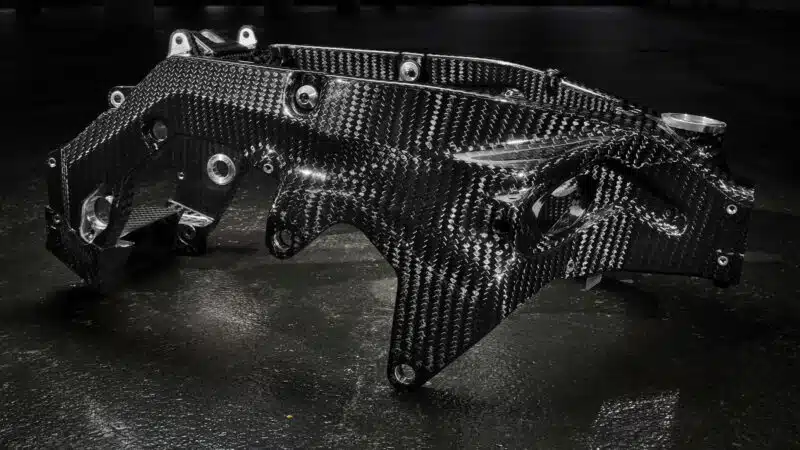

KTM introduced a carbon-fibre swingarm at Le Mans in 2019 and immediately found around half a second

KTM

“They’ve most likely got it stiffer than the original frame, so the suspension can do its job, rather than the frame flexing,” he continues. “Whether you are using a steel or aluminium frame it’s basically a piece of elastic. It might be an extremely stiff piece of elastic but it’s still a piece of elastic and with elastic you have no control over it, no damping.

“So you build the chassis as stiff as you can make it in that area and then you work on the suspension to control the bike. If the frame isn’t totally stiff you’re confusing the suspension.”

And then there’s the weight-saving. The RC16’s frame is two kilos lighter than the steel frame, a useful gain.

“Light weight is everything. When I worked for Kenny I kept banging on about weight, but nobody seemed to worry about it. It was kind of, ‘We’ll worry about weight later, let’s get the thing going around the track first’. No! You have to build the bike from the beginning with weight in mind.”

Barnard (second left) with his carbon-fibre McLaren MP4 driven by Niki Lauda at Monza in 1983

Barnard is still fascinated by MotoGP, because of the challenges of making a chassis work at extreme lean angles.

“When you look at a bike leaning past 60 degrees you think, ‘how the hell do they get the load into the contact patch of the tyres?’ And when the rider goes over a bump the forces are going into the tyre vertically, so all the forces are trying to twist the swingarm and bend the forks.”