In 2004 Furusawa engineered the big-bang YZR-M1 engine that Rossi needed to beat Honda’s RC211V. In 2006, when the M1 was beset with chatter problems, caused by a too-rigid chassis, Furusawa created mini mass-dampers – oil-filled canisters, with weights and springs inside, which were attached to the front forks. The idea was that the opposing weights would damp out the chatter. But they didn’t work.

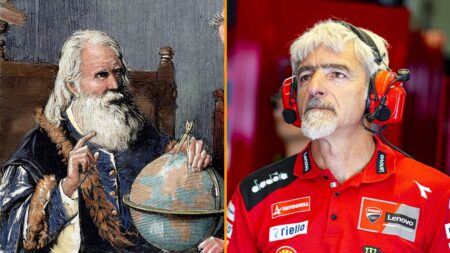

Thus no other engineer has been so successfully involved in a MotoGP project, from design and development of the entire motorcycle to daily trackside input than Dall’Igna, which makes Bagnaia, Dall’Igna, Desmosedici the greatest MotoGP trinity of all time.

When the former Aprilia engineer arrived at Ducati before the 2014 season he took charge of a race shop that was in the same deep hole in which HRC currently finds itself. The company hadn’t won a race for years.

Dall’Igna’s contract with Ducati gave him total control – otherwise, what would be the point? Factory rider Andrea Divizioso called the GP14, the last pre-Dall’Igna Desmosedici, “hardly a motorcycle”.

Dall’Igna is a constant presence in the factory garage, overseeing every stage of every operation at every race

Dall’Igna knew the radical ideas percolating through his brain would transform MotoGP and bring him into conflict with old-school riders who weren’t too sure about his futuristic plans. Dall’Igna famously had many arguments with Dovizioso, who wanted to continue racing motorcycles, not two-wheel Formula 1 cars. Dovizioso went, Dall’Igna stayed.

“The engineer must be strong with his riders,” says Dall’Igna.

There are two particular Dall’Igna concepts that have helped make the Desmosedici all-powerful in MotoGP.

Everyone knows a motorcycle has two tyres. But he was arguably the first engineer to understand that you can and must make full use of both tyres at all times.

Why focus on stopping the bike with the front tyre, just because load is thrown onto that tyre during braking? Why not rebalance the entire motorcycle to keep it more horizontal during braking, so the rider can use the bigger rear tyre’s greater grip to help stop the bike in the shortest distance possible?

This is why Ducati’s rivals say they can’t match the Desmosedici on the brakes.

Of course it’s no coincidence that the bike gets better every time it’s equipped with a better rear slick. When Bridgestone tyres (great front, poor rear) were replaced by Michelins (poor front, great rear) in 2016 the Desmosedici started winning again. When Michelin introduced an improved rear in 2020 the bike began to win lots of races (once Dall’Igna had replaced his old-school riders with youngsters) and this year’s new rear has made Ducati just about unbeatable.

And why not try increasing the front tyre’s grip exiting corners? A big limiting factor during the first stages of acceleration is bike balance shifting rearwards when the rider opens the throttle, which reduces the front-tyre’s contact patch and therefore grip, so the bike runs wide, unless the rider waits to open the throttle fully.

Dall’Igna and Bagnaia celebrate winning the 2023 season-opening Portuguese GP

Ducati

The answer is obvious when you think about it: you transform horsepower into grip, because grip is even more important than horsepower (and it helps if your engine has power to spare, thanks to the genius of Fabio Taglioni, Ducati’s first great engineer, who introduced desmodromic valve control, following chats with his friend Enzo Ferrari).

So you attach downforce accoutrements to the front of the bike, which create drag but more importantly increase load on the front tyre under acceleration. Now the rider can open the throttle harder and sooner, without running wide. The wings also increase performance once the rider is going straight, by minimising wheelies, allowing the rider to use more throttle.

These are two of many Dall’Igna concepts that have created a level of dominance unseen since the glory days of Honda’s NSR500, which held the record for most wins in a season, until the Desmosedici bettered it last year.