So what has changed? Management, obviously, but since Schramm’s statement the difference between WSB and MotoGP has become more than marginal.

In 2019 WSB raced in Europe, the USA, South America, Qatar and Thailand. Now the series numbers only twelve rounds, all in Europe, apart from the season-opening Australian event. Meanwhile MotoGP has grown from 19 to 21 rounds, 12 in Europe, nine outside.

Last year’s spectator numbers mirror those figures: the 2023 WSB season attracted 593,000 trackside fans, against 2.9 million in MotoGP.

Those trackside figures make MotoGP five times bigger than WSB. These numbers are, of course, a factor of Dorna growing MotoGP and shrinking WSB to make MotoGP motorcycling’s undisputed premier class, like Formula 1 in car racing.

This presumably is Dorna’s vision – that the manufacturers spend their money on MotoGP, while WSB becomes a low-cost series supported mostly by importer- and privateer-backed teams.

Dorna’s sale to Liberty Media will most likely continue this trend, because WSB wasn’t mentioned once during a 55-minute media conference following Liberty’s acquisition of Dorna earlier this month. Will Liberty sell WSB? Highly unlikely, because why give a rival a way into the sport?

Flasch backed up his comments to German magazine Motorrad with these words in the latest edition of Dutch magazine KicXstart, “We will evaluate very carefully whether other classes and formats indeed make sense for us”.

These statements suggest BMW is looking seriously at MotoGP, most likely from 2027, when new technical regulations are introduced – always the best time to enter a championship.

Dorna’s efforts to get BMW into MotoGP took a weird turn a couple of years ago. When Suzuki announced its withdrawal from the championship, Dorna wanted BMW to take Suzuki’s GSX-RR MotoGP bikes and race them with BMW badges. But Schramm was in charge then and why would a proud German manufacturer want to race Japanese motorcycles?

So far, the short-lived 2006 prototype is as close as BMW has come to entering MotoGP.

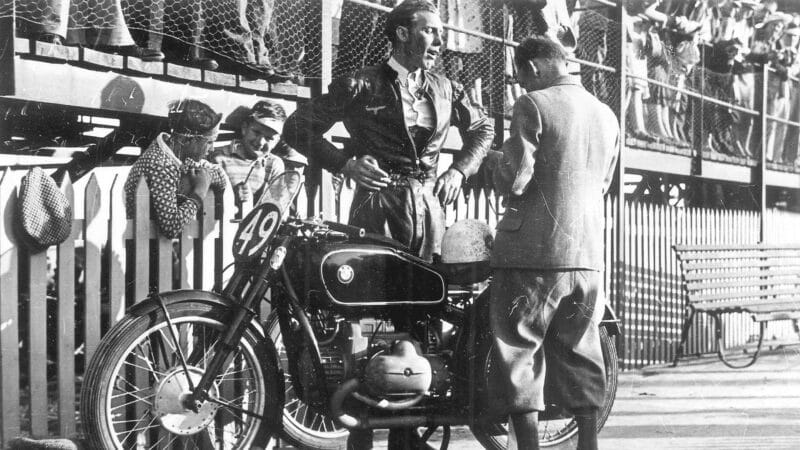

Former 125cc and 250cc world champion Luca Cadalora testing the 2006 BMW Oral MotoGP prototype. The engine was basically three cylinders off a BMW Formula 1 car

BMW subcontracted this project to Oral Engineering, an Italian company founded by Mauro Forghieri, a former Ferrari Formula 1 engineer. The MotoGP prototype was tested by former MotoGP riders Jeremy McWilliams and Luca Cadalora.

The 800cc triple (MotoGP engines were due to be limited to 800cc from 2007) was basically three cylinders off BMW’s 2.4-litre V8 Formula 1 car engine.

This in spite of the fact that Aprilia had raced the first three seasons of MotoGP with its 990cc Cube, which was essentially three cylinders off Cosworth’s three-litre V10 F1 engine. The Cube proved that using F1 engine tech in MotoGP is little more than a great way of making millionaires out of surgeons and osteopaths.