Pitlane experts believed that the M1’s front end didn’t give riders the quality of feedback required to rush into corners at race-winning speed. In fact that was only half the problem, as Rossi discovered the first time he rode the M1.

Rossi and Honda didn’t part on the best of terms at the end of 2003, so he was refused permission to ride rival motorcycles until his HRC contract expired at the end of December. Thus he had his first outing on the M1 on January 24, 2004, during the opening pre-season tests at Sepang, Malaysia, 12 weeks before the first grand prix in South Africa.

At that stage the M1 was so flawed that most people assumed Rossi and Yamaha would spend the 2004 season addressing the bike’s many problems, then go for the title in 2005, Yamaha’s 50th anniversary.

Instead Rossi and his brilliant crew chief Jeremy Burgess made huge forward strides on the very first day of that three-day test in Malaysia.

“Sincerely, I expected bigger problems, but more or less the bike is okay,” said Rossi at Sepang. “It has some things that are less than Honda, but also some good things. Basically it’s not so bad.”

That statement blew everyone’s minds – surely he was being economical with the truth?

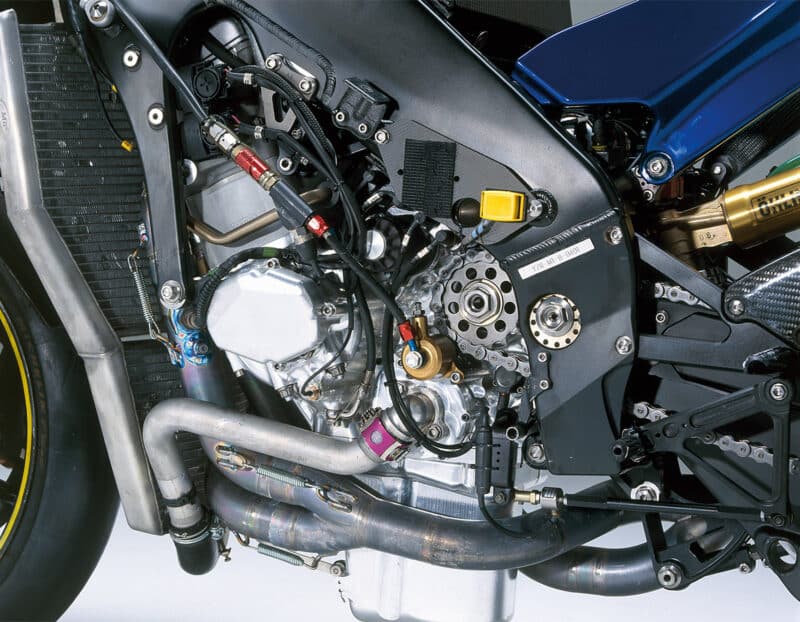

Rossi’s M1 stripped at the end of the 2004 season – the bike was still an unpolished diamond. The 2005 iteration was much improved

Rossi rode his first laps on Sunday the 24th and soon found out why Barros and Yamaha’s other riders had been losing the front and hitting the ground so often.

Pretty much every time he hit the brakes he nearly lost the front. Usually this would suggest poor bike balance and not enough load on the front tyre, because riders need to load the tyre during braking to generate heat and therefore grip. Burgess and his crew checked the data, searching for clues. What they found was quite a shock.

MotoGP engine-braking systems usually keep the throttle butterflies (which regulate fuel/air flow in the injection system) open during braking, even when the rider has the actual throttle closed, because if the butterflies are fully closed there’s too much negative torque, which will lock the rear tyre. For some bizarre reason the M1’s electronics had the front tyre linked into the system, so when Rossi locked the front tyre the engine increased its rpm. A surefire way to make your riders crash!

This is why Barros and other M1 riders had landed on their heads so often during 2003, because the bike started to accelerate when they locked the front tyre! Yamaha simply wrote the front brake out of the M1’s engine-braking program and the problem was solved.

Mostly, anyway. Rossi still thought the front tyre locked too easily. He also told Burgess and the multitude of Yamaha engineers in his garage that the bike was difficult to turn and that the steering got mysteriously heavy when the forks were fully compressed on the brakes.

Perhaps the air-intake rubber under the front of the fairing was getting squashed against the mudguard, suggested JB. Impossible, said Yamaha. So Rossi’s crew removed the fork springs, bottomed the bike and the intake rubber was hard against the mudguard!

This didn’t only affect handling and steering, it also shut off much of the air intake, which wasn’t good for engine response.

Rossi in 2004 with (left to right) Michelin technician Pierre Alves, mechanic Alex Briggs (behind Alves), crew chief Burgess and data engineer Matteo Flamigni (now Marco Bezzecchi’s crew chief)

Getty Images

How come Yamaha had failed to notice these problems during 2003, let alone fix them, whereas JB sorted them in a few hours? JB and the crew were certainly perplexed, but they weren’t worried, because they were making giant leaps forward without much effort, simply using JB’s straightforward approach to getting the best out of a motorcycle, the so-called KISS principle: Keep It Simple, Stupid! And Yamaha was certainly learning fast.