On their arrival at Spa, Tait’s “ragbag team” was assigned the same pit area as the mighty MV Agusta squad – like the village tramp trying to dine with the lord of the manor – which got the weekend off to a tricky start.

“At first the MV mechanics could not believe that the tatty Transit was entering the pit of the great and mighty and duly refused entry,” Williams continued. “The order of the day then became fisticuffs and things, so Arthur [Jakeman, tuner and mechanic], who is quite large, showed the smallest Italian his fist, and the trusty van, which I might add was also the mobile hotel, cookhouse, workshop and perhaps with a bit of luck a resting place for a passing maiden, was in. The MV mechanics moved their beloved machines as far as possible from this new outfit, worried they might catch oil leaks and things.”

Forty-year-old Tait was a brave and gifted rider and the T100 was fast enough to lead the first lap of the Belgian GP, before Giacomo Agostini came past on his 80-horsepower MV four, which enjoyed a 30mph top-speed advantage over the Triumph, which nudged 140mph on the downhill sections. At the chequered flag Tait was the only rider on the same lap as Ago, the podium completed by fellow Brit Alan Barnett, riding a Matchless Metisse.

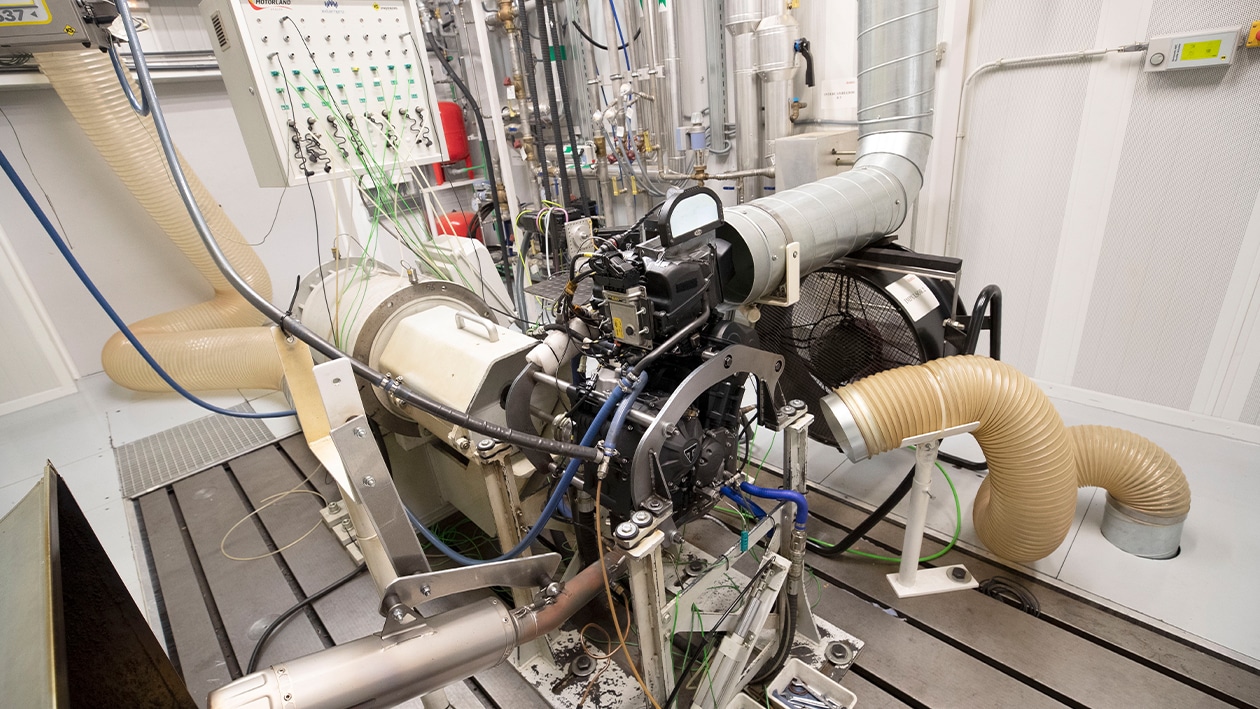

ExternPro technical director Trevor Morris oversees the rebuilding and supplying of Triumph’s 765 engines to the 32-rider Moto2 grid

Triumph

The team received a hero’s reception (from the workers, not the management) on its return to Meriden. Williams again, “They returned to the factory to great joy and jubilation from Doug Hele and all the workers that drilled holes and things and did the putting of the motorcycles together. They all knew it was good for the order men and perhaps more pennies in their wages sack, as they were all good people and proud of their craft”.

Triumph’s oily efforts at Spa were a million miles away from Triumph’s official entry into Moto2 fifty years later.

During that half century’s absence, GP racing had changed utterly, from the largely amateur Continental Circus to a global corporate enterprise.

“The usual discrepancy between engines is between one and 1.3 horsepower”

Triumph’s job is to supply engines to 32 riders at 22 GPs, stretching from March to November and from Argentina to Japan. It’s a massive undertaking, run with military precision by Triumph and ExternPro, the Dorna-owned company that builds the engines at Aragon MotorLand in Spain.

During Triumph’s first five seasons in Moto2 – its current contract goes to the end of 2029 – its 765 engine covered more than 800,000 miles, slightly more than a return trip to the moon.

The 765 make 142 horsepower, good enough for 187mph (300km/h) at Mugello last June. The hard-worked engines are replaced and rebuilt every third race, with ExternPro toiling throughout the season to rebuild engines, which are allocated randomly via a lottery system. All engines are dyno’d before allocation, to ensure fairness – the usual discrepancy is between one and 1.3 horsepower.

All Moto2 engines are dyno’d at ExternPro before allocation to ensure horsepower varies by no more than 0.9%

Triumph

“We learn a lot from Moto2 that we can bring back into our road bikes,” says Paul Stroud, Triumph’s chief commercial officer. “There are a few key areas, like performance – when we started Moto2 in 2019 the 765 Street Triple had 123PS (121 horsepower), now it’s got 130. Some of that came from improved combustion and cylinder pressure, plus we’ve made a marked improvement in fuel efficiency.

“This year’s Moto2 engine has a small improvement in power and revs, but the most exciting thing is the requirement to run a 40% sustainable fuel mix. This gives us a very interesting learning platform to see how we can bring that technology into our road engines. Who knows, it may present a different route forward to change electric power.

“We are running this fuel on dynos at Triumph and at ExternPro. It makes no difference to what we can deliver in terms of power, which is quite exciting.”