In Britain he became an RAF engineer and not long after the war he joined Norton. His speciality was the concept of squish – by aggressively squishing the air/fuel mixture as the piston reaches top-dead centre gas turbulence is increased, which improves air/fuel mixing for better combustion and increases heat transfer for better cooling.

Kuznick’s work on Norton’s singles therefore increased both horsepower and reliability. Without his input it’s likely that Norton would never have won the MotoGP world title, because its machines needed all the power they could get to beat their main rival, the faster four-cylinder Gilera 500.

“Leo was a brilliant engineer – in my opinion he was never given the credit he was due by Norton,” wrote 1951 MotoGP champion Geoff Duke in his autobiography, In Pursuit of Perfection. “He was responsible for a phenomenal 30% increase in power.”

This was the funny thing about the second and last British motorcycle to win the MotoGP title. The winning Norton 500 used an engine tuned by a Pole and a chassis designed by an Irishman, Rex McCandless, whose renowned Featherbed design remained the blueprint for motorcycle frames into the 1980s.

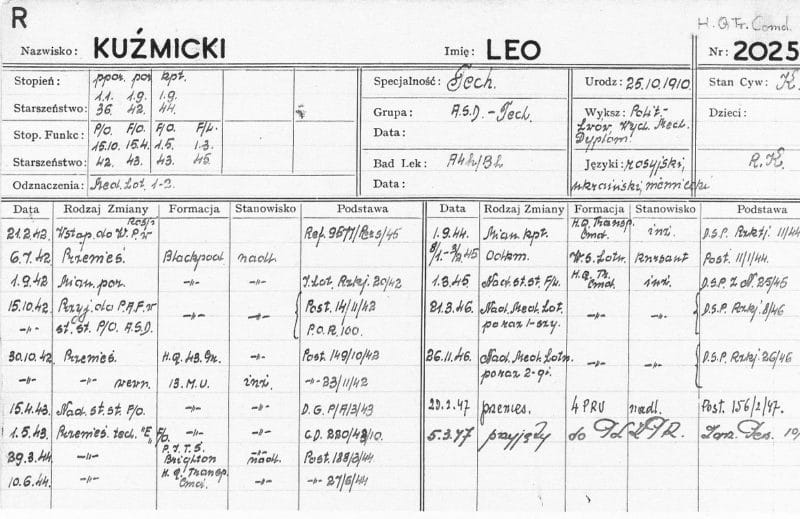

Kuźmicki’s RAF papers record his career from arriving in Britain in July 1942, after almost three years in a Russian labour camp, to his demobbing in 1947

Ministry of Defence

McCandless initially tried to sell his invention to Triumph, until a Triumph executive told him during a business dinner that his company would never use a “foreign invention” in its motorcycles. McCandless, not a man to be messed with, upended the dinner table in the executive’s face and tried Norton next.

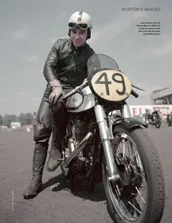

Duke was won over by the Featherbed the first time he tried it. “I soon realised that this machine set an entirely new standard in roadholding,” he wrote.